Prediction and Reactions

Prediction: By 2020, intelligent agents and distributed control will cut direct human input so completely out of some key activities such as surveillance, security and tracking systems that technology beyond our control will generate dangers and dependencies that will not be recognized until it is impossible to reverse them. We will be on a ‘J-curve’ of continued acceleration of change.

An extended collection hundreds of written answers to this question can be found at: http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/2006survey/autonomoustechnolgy.xhtml

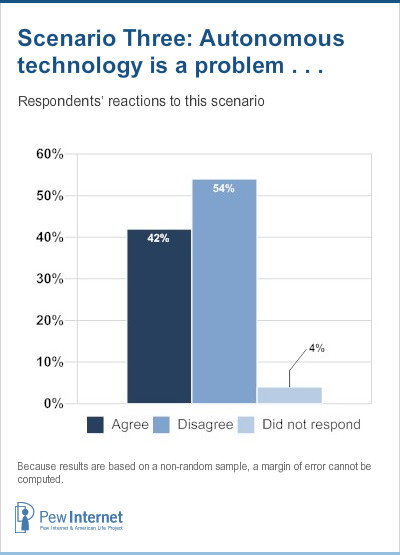

Overview of Respondents’ Reactions

Those who disagreed with this scenario generally said the humans who design technology will have no difficulty controlling it – but some noted a fear of the people who could control new technology. Those who agreed with the scenario often cited the increasing complexity of human-made systems and decreasing oversight of technology. They urged “human intervention.”

Of course the responses to this scenario, as with all on the survey, were shaped by the experiences participants have had. Many respondents – those who disagreed and those who agreed – were moved to react by comparing this proposed future to a science-fiction plot (“The Matrix,” “The Terminator,” “Frankenstein”). The answers were also shaped by how closely people read every word of the scenario. The group disagreeing included many engineers and computer scientists – many of them taking issue with the phrase “impossible to reverse” – while many sociologists, government workers and network policy makers found some of this scenario’s points to be quite worthy of serious discussion. Again, the scenario was written to engender engaged discussion, not to propose what we see as the likeliest future.

Technology architects generally answered by saying that humans will retain control of any system they design. “Agents, automated control and embedded computing will be pervasive, but I think society will be able to balance the use,” wrote David Clark of MIT.15 “We will find these things helpful and a nuisance, but we will not lose control of our ability to regulate them.”

Internet Society board chairman Fred Baker wrote, “We will certainly have some interesting technologies. Until someone finds a way for a computer to prevent anyone from pulling its power plug, however, it will never be completely out of control.” Pekka Nikander of Ericcson Research and the Internet Architecture Board responded: “As long as the everyday weapon-backed power systems (e.g. police force) are kept in human hands, no technical change is irreversible. Such reversion may take place as a socioeconomic collapse, though.”

“Completely automating these activities will continue to prove difficult to achieve in practice. I do believe that there will be new dangers and dependencies, but that comes from any new technology, especially one so far-reaching,” argued Thomas Narten, Internet Engineering Task Force liaison to ICANN, and chief of IBM’s open-internet standards development.

Robert Kraut of the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, sees the development of automated systems running smoothly. “Certainly intelligent agents and distributed control will automate some tasks,” he wrote. “But heavy automation of tasks and jobs in the past (e.g., telephone operators) hasn’t led to ‘dangers and dependencies.’“

The most dismissive reactions to the scenario came mostly from those who are involved in writing code and implementing the network. Anthony Rutkowski of VeriSign, over the past decade a leader with the Internet Society and International Telecommunication Union, wrote: “Autonomous technology is widespread today and indispensable. Characterizing it as a ‘problem’ is fairly clueless.” Programmer and anti-censorship activist Seth Finkelstein responded, “This is the AI bogeyman. It’s always around 20 years away, whatever the year.” And Alejandro Pisanty, of ICANN and the Internet Society, wrote, tongue-in-cheek: “This dysfunctional universe may come true for several types of applications, on and off the network. We better start designing some hydraulic steering mechanisms back into airplanes, and simple overrides of automatic systems in cars. Not to speak about pencil-and-paper calculations to get back your life’s savings from a bank!” Hal Varian of UC-Berkeley and Google wrote, “It’s a great science fiction plot, but I don’t see it happening. I am skeptical about intelligent agents taking over anytime soon.”

Leigh Estabrook, a professor at the University of Illinois, stated: “Human beings always have control, but they often choose to give it up. For example, when the airline agent tells me I cannot do something because ‘the computer won’t allow it.’ Human beings have made choices to program that computer that way, to limit human abilities to override functions. I could also say I agree since we do seem willing to give up control to systems, and increasingly legislators and the judiciary have allowed surveillance, security, and tracking systems that would seem to me – and to many others – to be dangerous.”

Many who see dangers or predict negative impacts discuss unforeseen consequences of surveillance.

Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), sees extreme danger in the autonomous technology scenario. “This is the single greatest challenge facing us in the early years of the 21st century,” he responded. “We are constructing architectures of surveillance over which we will lose control. It’s time to think carefully about ‘Frankenstein,’ The Three Laws of Robotics, ‘Animatrix’ and ‘Gattaca.’”

Amos Davidowitz of the Institute of World Affairs, responded this way: “The major problem will be from providers and mining software that have malignant intent.” His concerns about surveillance were echoed by many respondents, including Michael Dahan, a professor at Sapir Academic College in Israel, who wrote, “Things may be much worse with the increasing prevalence of RFID chips and similar technologies. Before 2020, every newborn child in industrialized countries will be implanted with an RFID or similar chip. Ostensibly providing important personal and medical data, these may also be used for tracking and surveillance.”

Elle Tracy, president and e-strategies consultant for The Results Group, suggested overconfident humans may allow this scenario to unfold. “The only reason I can agree with this is because of my first-hand experience within the technology industry,” she wrote. “The people who write this code are so proud of their work – and they should be – that the rational, real-world checks and balances that should be implemented on their results fall into a second-class-citizenry level of import. Until testing, bug fixing, user interfaces, usefulness and basic application by subject matter experts is given a higher priority than pure programmer skill, we are totally in danger of evolving into an out-of-control situation with autonomous technology.”

Robert Shaw, internet strategy and policy adviser for the International Telecommunication Union, had other concerns: “Even in today’s primitive networks, there is little understanding of the complexity of systems and possible force-multiplier effects of network failures,” he wrote. “The science of understanding such dependencies is not growing as fast as the desire to implement the technologies.”

Some respondents pointed to the fact that certain technological systems are already suffering due to a lack of well-intentioned human input throughout the processes they are built to accomplish. “Systems like the power grid are already so complex that they are impossible to predictably control at all times – hence the periodic catastrophic failures of sections of grid,” wrote author and social observer Howard Rheingold. “But the complexity and interconnectedness of computer-monitored or controlled processes is only a fraction of what it will be in 15 years. Data mining of personal traces is in its infancy. Automatic facial recognition of video images is in its infancy. Surveillance cameras are not all digital, nor are they all interconnected – yet.”

Douglas Rushkoff, teacher and author of many books on net culture sees a need to take action. “If you look at the way products are currently developed and marketed,” he explained, “you’d have to say we’re already there: human beings have been taken out of the equation. Human intervention will soon be recognized as a necessary part of developing and maintaining a society.”

Paul Craven, director of enterprise communications, U.S. Department of Labor, wrote: “History has shown that as technology advances the abuse of that technology advances. History has also demonstrated that we do not control technology as much as we think we do.”

Another government official, Gwynne Kostin, director of Web communications for U.S. Homeland Security, pointed out the inadequacies of an automated system during a recent natural disaster in responding to this scenario. “This is an extension of the current status,” she wrote. “A suggestion for an XML standard for emergency deployments during Hurricane Katrina ignored the fact that there was no electricity, no internet access, decreasing batteries and no access to equipment that was swamped. Non-technical backups will become increasingly important – even as we keep forgetting about them. We will need to listen carefully to people on the ground to assess – and plan for – events in which we have no (or non-trustworthy) technology.”

There also were concerns about inequities created by computer networks. Arent Greve, a professor at the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration, wrote, “There will be a trend in this direction, not as extreme as displayed in the above scenario, but bad enough that we will experience injustice, I think that some of those systems may be reversible, others may not. I would guess a probability of about 30% that such systems develop.” And David Weinberger of Harvard’s Berkman Center wrote: “DRM and ‘trusted computing’ initiatives already are replacing human judgment with algorithms that inevitably favor restricted access to the content on our own computers.”

Alik Khanna of Smart Analyst Inc. in India responded that advances in nanotechnology and robotics will build an increasing reliance on machines. “Whether the development of AI will lead to self-awareness in machines, time will tell,” he wrote.

Some say elements of this scenario will take place, but predict humans will not lose all control.

“I agree, but this is not a doomsday scenario,” wrote Mark Gaved of the Open University in the UK. “The development of these technologies will echo previous technologies with similar curves, unexpected developments and unauthorised appropriations by grassroots groups.”

[into this scenario already]

Charlie Breindahl of the IT University of Copenhagen wrote, “I agree that it is a very real danger. However, I think that our present thinking about how automation and distributed computing works is naïve. In the year 2020, the general public will be much more aware of how to utilize their agents and control schemes. We should see a much more ‘AI-literate’ population, if not in 2020, then in 2040.”

Michael Reilly of Globalwriters, Baronet Media, wrote, “While a few activities could spin off course, most really problematic issues will be spotted early and repaired. Also, monitoring which alerts humans to problems will become a high-order business on its own, incorporating ‘self-healing’ networks equipped with alarms when boundaries are exceeded.”

Robin Lane, an educator and philosopher from the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, wrote, “The desire for convenience, for ease of use, for the removal of tedious, laborious tasks is – in my opinion – inherent in us as beings. As such we will continue to use and abuse technology to make our lives easier. The price for this is increased dependency on the technology.”

Several suggest working to avoid “unintended consequences.”

Some respondents specified that humans must plan in advance to build the best outcome for an automated future. “I truly do agree that there will be nearly complete automation of such boring-to-humans activity as surveillance, security and tracking systems,” wrote Glenn Ricart, a member of the Internet Society Board of Trustees and the executive director for Price Waterhouse Coopers Research. “There will clearly be unintended consequences, some of which may endanger or take human life. However, I don’t believe it will be impossible to reverse such things; indeed, we will continue to perfect them while undergirding them with something like Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics.”

“The fact that this question is being asked/asserted suggests that it will NOT happen.,” wrote Kerry Kelley of Snapnames.com. “Enough healthy paranoia exists among the people on the inside – those creating the standards – that others who might purposefully, or accidentally, unleash these kinds of problems will be effectively neutralized.”

Henry Potts, a professor at University College in London, expressed concern over potential economic impact. “The use of standard decision-making software by stock market traders has already led to effects outside of what we planned or wanted,” he wrote. “I don’t fear robots looking like Arnold Schwarzenegger taking over the world, but unexpected and unwanted effects of distributed control are feasible.”

Jim Archuleta, senior manager for government solutions for Ciena Corporation wrote, “In some cases, reversal of the processes will be difficult and nearly impossible. There are scenarios where processes based on automation and intelligence based on rules and identities will miss ‘outliers’ and ‘exceptions’ thereby resulting in mistakes, some of which will be life-threatening.”

Lilia Efimova, a researcher with Telematica Instituut in the Netherlands, wrote, “This is a possible scenario, so I believe there is a responsibility for internet researchers in that respect to recognize those dependencies in advance and to act on preventing dangers.”

Sabino Rodriguez of MC&S Services responded that the European Commission is already assigning “studies, proposals and investments” into avoiding negative consequences of new technologies. And Sean Mead, an internet consultant, wrote, “Science fiction has warned of nearly any threat that autonomous technology can raise. There will be problems caused by autonomous tech, but, like germs provoking an immune-system response, the eventual effect of the initial damage will be to install safeguards that protect us from long-lasting damage.”

Social power will grow along with technological power – perhaps thwarting runaway technology.

Several survey participants said this scenario also presents some positive aspects. Ted Coopman, a social science researcher and instructor at the University of Washington, sees the formation of a “new bottom-up, global, civil society” thanks to autonomous technology “in the form of ultra-structure capabilities that allow almost anyone to project power with little or no cost.”

He continued: “The repertoires of individuals and groups will be readily available and successful or attractive ones will spread and scale rapidly. The aggregate adoption will cause huge and likely unpredictable shifts in social, political, economic arenas. People will no longer favor incumbent systems, but will move to systems that make sense to them and serve their needs. This will force incumbent systems to adapt quickly or fail. Governmental protection of incumbent corporate and social power will lose much of its effectiveness as a force of social control. These parallel systems to serve people’s needs will arise via digital networks.”

Mary Ann Allison, a futurist and chairman and chief cybernetics officer for The Allison Group, responded: “While this scenario is clearly a danger, we don’t yet understand how powerful fully-connected human beings can be.”

And Rob Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, and formerly director at the U.S. Congressional Office of Technology Assessment, responded, “The more autonomous agents the better. The steeper the ‘J curve’ the better. Automation, including through autonomous agents, will help boost standards of living, freeing us from drudgery.”

Mark Poster, an authority on the ways social communications have changed through the introduction of new technologies, wrote, “The issue will be how humans and information machines will form new assemblages, not how one will displace the other.”

“Autonomous systems will not become a serious problem until they are sophisticated enough to be conscious … As it stands now, they are simply tools – advanced tools, but tools nonetheless. True AI is still 50-100 years away,” argued Simon Woodside, CEO, Semacode Corp, Ontario, Canada.

Where does ‘autonomous technology’ stand now?

Distributed control systems – those with remote human intervention – have long been used across the world to handle various tasks, including the operation of electrical power grids and electricity-generation plants, environmental control systems, traffic signals, chemical and refining facilities, water-management systems and many types of manufacturing. Systems are becoming more automated daily, as pervasive information networks are being invisibly woven into everything everywhere, helping us manage a world that becomes exponentially more complex each year.

Many operations are being handled by small microelectromechanical systems – better known as MEMS. Billions of these devices are already woven into our buildings, highways, and even our forests and other ecosystems; they are found in personal devices, from our automobiles to printers and cell phones. The market for MEMS hit $8 billion in 2005, with a forecast for growth to more than $200 billion by 2025, according to Joe Mallon of Stanford University.16

Some programmable, remote information devices now in use are called “agents” or “bots.” Agents automatically carry out tasks for a user: sorting email according to preference, filling out Web page forms with stored information, reporting on company inventory levels, observing changes in competitors’ prices and relaying statistics, mining data to detect specific conditions. Bots are programmed to help people who play online games perform various tasks; they are also used online to aid consumers in finding products and services – these shopping bots use collaborative filtering.

MEMS, agents and bots are self-contained tools designed and distributed by people who monitor them and replace or remove them from a network when necessary. They are autonomous to some extent in that they are capable of functioning independently to meet established human-set goals. Most of them do not possess any artificial intelligence. Intelligent agents have the ability to sense an environment and adapt to changes in it if necessary, and they have the ability to learn through trial and error or through example and generalization. MEMS, agents and bots are the reality today. In the near future, as computing and data storage become more advanced and nanotechnology and artificial intelligence systems are more nearly perfected, it is expected there will be far less direct human input in the day-to-day oversight of human-built systems.

Where might this technology take us in the future?

Many of the sophisticated operational systems developed in the next few decades will be invisible or nearly so. Nanoelectromechanical systems – 10,000 times smaller than the width of a hair – are being developed, and thousands of nano-related patents have already been issued. Most who predict a future that sounds a great deal like a science-fiction plot are those who see the continued development and convergence of networked nanotechnology, robotics and even genetics.

Among the seemingly “extreme” predictions made by various respected tech experts in various reports issued over the past few years are:

- Networked “smartdust” devices, or “motes” – these would be the size of a dust particle, each with sensors, computing circuits, bidirectional wireless communication and a power supply. They could gather data, run computations and communicate with other motes at distances of up to about 1,000 feet. A concentrated scattering of a hundred or so of these could be used to create highly flexible, low-cost, low-power network with applications ranging from a climate control system to earthquake detection to the tracking of human movement.17

- Advanced robots – British Telecom futurologist Ian Pearson has said robots will be fully conscious, with superhuman levels of intelligence by the year 2020. In a 2005 interview with The Observer, a UK newspaper, he said, “Consciousness is just another sense, effectively, and that’s what we’re trying to design in a computer.” And, he added, “If you draw the timelines, realistically by 2050 we would expect to be able to download your mind into a machine, so when you die it’s not a major career problem.”18

In order to prepare in advance for a future that is likely to be filled with accelerating developments related to autonomous technologies, select leaders have founded watchdog organizations, held conferences and created research projects. Among them are the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology – www.crnano.org – and the Acceleration Studies Foundation – www.accelerating.org. In addition, Battelle – www.battelle.org – and the Foresight Institute – www.foresight.org – are two major non-profit organizations conducting ongoing technology roadmap projects investigating the implications of autonomous technologies.

Acceleration to a “singularity” is predicted by some.

Respected professor and author Vernor Vinge and inventor Ray Kurzweil – author of The Singularity is Near and a winner of the U.S. National Medal of Technology and the Lemelson-MIT Prize – have been the most vocal proponents of the idea that a “technological singularity” will occur during this century. This “singularity” is defined as the point at which strong artificial intelligence or the amplification of human intelligence will change our environment to an extent beyond our ability to comprehend or predict.19 Kurzweil has written that paradigm shifts will lead to “technological change so rapid and profound it represents a rupture in the fabric of human history,” and he says this will happen by 2045.20

Other top thinkers see this sort of future: Robotics researcher Hans Moravec has projected that nano-scale machines equipped with AI could displace humans in the next century. Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom wrote a 2002 essay titled “Existential Risks” about the likely threats presented by the Singularity. AI researcher Hugo de Garis wrote a 2005 book titled “The Artilect War: Cosmists vs. Terrans – A Bitter Controversy Concerning Whether Humanity Should Build Godlike, Massively Intelligent Machines.”

The Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence (www.singinst.org) was founded to further discussion of potential futures based on this idea. A great many other respected experts dispute the idea of the Singularity, including physicists Theodore Modis21 and Jonathan Huebner,22 who have argued the exact opposite – that innovation is now actually in decline.

While few respondents to the “autonomous technology” scenario in this survey included the “singularity” idea in their remarks, most said such an event will arrive long after 2020, if ever. Barry Chudakov, principal partner in the Chudakov Company, wrote, “We will cut direct human input in a variety of human activities and this will cause problems. This is already causing problems and we’re not yet near the ‘singularity’ where we’re likely headed. However, the notion of ‘technology beyond our control’ is an alarmist construct … we are learning as we are making mistakes. So while we are hell-bent on acceleration of change, I believe we will also rethink and respond to those systems that seem to be running away from us. We have the time to understand our relationship with technology and I think we will not get lost on a dead-end J-curve.”

Educational consultant Jeffrey Branzburg wrote, “Although I agree with the concept of a ‘J-curve’ of continued acceleration of change, as discussed in Ray Kurzweil’s The Singularity is Near, I believe it is not a problem. The ingrained human system of checks and balances will continue to keep the potential dangers under control. (By ingrained human system of checks and balances I mean the propensity of people to resist when they believe an entity has attained a higher than desired degree of control and influence.)”

Daniel Wang, principal partner of Roadmap Associates, wrote: “This is one of the scariest consequences of our light-speed technological advancement. Hollywood fiction will become reality.”

“The question has an overly dramatic spin to it, but the trend is correct,” argues Paul Saffo, director of the Institute for the Future. “Now, fear of enslavement by our creations is an old fear, and a literary tritism. But I fear something worse and much more likely – that sometime after 2020 our machines will become intelligent, evolve rapidly, and end up treating us as pets. We can at least take comfort that there is one worse fate – becoming food – that mercifully is highly unlikely.”