Predictions and Reactions

Prediction: By 2020, the people left behind (many by their own choice) by accelerating information and communications technologies will form a new cultural group of technology refuseniks who self-segregate from ‘modern’ society. Some will live mostly ‘off the grid’ simply to seek peace and a cure for information overload, while others will commit acts of terror or violence in protest against technology.

An extended collection hundreds of written answers to this question can be found at:

http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/2006survey/ludditesoffthegrid.xhtml

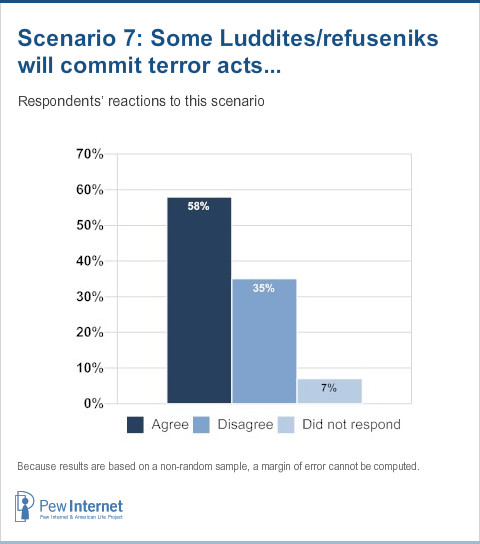

Overview of Respondents’ Reactions

Resistance to the effects of technological change may inspire some acts of violence, but most violent struggle will still emerge from conflicts tied to religious ideologies, politics and economics. Many people will remain “unconnected” due to their economic circumstances. Some will choose to be unconnected for various reasons – all the time or sometimes.

The word “Luddite” has come into general use as a term applied to people who fear, distrust, and/or protest technological advances and the changes they engender, and “refusenik” has become a term used to refer to people who do not want to participate in the actions routinely expected of a particular social group. The use of these commonly accepted terms drew some resistance and that added some thoughtful insights to the discussion. One respondent also suggested an alternative term. “There will be refuseniks, but not enough Unabombers to make it a trend,” wrote Barry Parr, an analyst from Jupiter Research,42 adding: “’Luddite’ will be retaken by ‘technoskeptics’ as a positive term.”

It is likely that most if not all people have some concerns about the negative effects of new technologies. The level of concern differs from individual to individual, and the reasons for such fears vary as well. It is impossible to gauge the numbers, but Kirkpatrick Sale, author of the book “Rebels Against the Future” wrote in his 1997 essay “America’s New Luddites”43:

“A Russian scholar claimed five years ago that there were as many as 50 to 100 million people who ‘rejected the scientific, technocratic Cartesian approach.’ Surveys show that in the U.S. alone more than half of the public (around 150 million people) say they feel frightened and threatened by the technological onslaught … in 1996 the trend was reported in magazines from Newsweek (‘The Luddites are Back’) to Wired (‘The Return of the Luddites’).”

Other strong voices have warned that technological advances are a threat to our humanity include Stephen Talbott, author of the 1995 book The Future Does Not Compute,44 and Theodore Roszak, the author of the 1994 book The Cult of Information: A Neo-Luddite Treatise on High Tech and a New York Times essay headlined “Shakespeare Never Lost a Manuscript to a Computer Crash.”45 Neil Postman’s Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology46 and his speech “Informing Ourselves to Death”47 are often quoted by those with concerns over the effects rendered by humans who wield new communications technologies. Clifford Stoll followed that with the book Silicon Snake Oil,48 and Bill Joy added his thoughts in an essay in Wired magazine titled “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us.”49

The most infamous neo-Luddite (and some who believe in the strictest definition of “Luddite” would say the only one) is Theodore Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber and author of a famous Manifesto,50 who took violent action to draw the world’s attention to his concerns, killing three and injuring 27 by sending 15 parcel bombs. “Of course there will be more Unabombers!” wrote Cory Doctorow of Boing Boing to this prediction.

Most respondents agreed with some aspects of this 2020 scenario, but there was a great deal of variability in the reasons for these responses. The elaborations provide many interesting insights. A notable number of respondents argued that religious ideologies have been an underlying cause of violent acts throughout human history, and that this prediction’s focus – the impact of advancing technologies – has rarely motivated destruction or death.

Naturally, people will protest – but to what extent?

Many survey respondents said there are always people who will not adopt the new technologies, but, they continue that this is to be expected and it really won’t make much of a difference in the great scheme of things. “This is a pattern repeated through history and will not change,” wrote Adrian Schofield, head of research for ForgeAhead, and a leader in the World Information Technology and Services Alliance from South Africa. “From ‘flower power’ to fundamental Islam, there will always be those who get their kicks from being outside of the mainstream of life.”

Douglas Rushkoff, author and teacher at New York University, responded, “They’re called cults and survivalists. Y2K was a fantasy for many who feel too dependent on the grid.”

[no violence]

Jim Warren, founding editor of Dr. Dobb’s Journal and a technology policy advocate and activist, wrote, “Yes, there will be some who live ‘off the grid,’ mostly disconnected from everyone except the few with whom they choose to have contact. There already are. There always have been! Yes, there will probably be very isolated incidents of a very few ‘attacks’ against information technology, just as there have always been attacks against all previous technologies – e.g., some people have been known to toss slugs into the coin-collection machines at tollbooths, or sugar in gas-tanks, and there were the occasional acts of the Luddites of a century ago.”

Alex Halavais, an assistant professor at Quinnipiac University and a member of the Association of Internet Researchers, wrote, “It seems natural that the social changes now under way will lead to those who act against them. What is less clear is whether they will do so without the help of technology. I suspect that effective challenges to these social and economic changes will only come about through the use of information technologies. The model here is not the Luddites, but the Zapatista movement.”

Violence is likely, some say, but it will be limited.

A number of respondents said they expect outbursts of violence motivated by human reactions to and expectations of technological advancements. “We’ll always have a few like Jim Jones and David Koresh, and a few misguided folks will follow,” wrote Joe Bishop, a vice president at Marratech AB.

Sean Mead of Interbrand Analytics responded, “Constant change will spook some into trying to slow everyone down through horrific and catastrophic terrorist attacks against the information infrastructure and all who rely upon it.”

“Today’s eco-terrorists are the harbingers of this likely trend,” wrote Ed Lyell, an expert on the internet and education. “Every age has a small percentage that cling to an overrated past of low technology, low energy, lifestyle. Led by people who only know the idealized past, not the reality of often painful past life styles, these Luddites will use violence to seek to stop even very positive progress. It is unclear to me how much of such aggression is the nature of the individual who seeks a ‘rationale’ for her/his more personalized or inherent rage versus the claimed positive goals of such actors.”

Jim Aimone, director of network development for HTC (the High Tech Corporation), wrote, “Terrorists exist today in the form of hackers, and I anticipate as we relinquish more controls to computers and networks they will be able to remotely commit any act they want.”

A number of respondents say protests will be tied to technological advances.

There were respondents who expressed concern over the potential for damaging acts tied to effects of advancing technologies. “The real danger, in my opinion, is the Bill Joy scenario: techno-terrorists,” wrote Hal Varian of the UC-Berkeley and Google.

“’Pro-life’ never became a term until technology advanced to the point that abortions could be done routinely and safely – now some fringe groups have turned to violence,” argued Philip Joung of Spirent Communications. “The increasing pervasiveness of technology could serve to anger certain individuals enough to resort to violence.”

Thomas Narten of IBM and the Internet Engineering Task Force responded, “It is not Luddites who will do this, but others. By becoming a valuable infrastructure, the internet itself will become a target. For some, the motivation will be the internet’s power (and impact), for others it will just be a target to disrupt because of potential impact of such a disruption.”

Martin Kwapinski of FirstGov, the U.S. Government’s official Web portal, wrote, “Information overload is already a big problem. I’m not sure that acts of terror or violence will take place simply to protest technology, though that is certainly a possibility. I do think that random acts of senseless violence and destruction will continue and expand due to a feeling of 21st century anomie, and an increasing sense of lack of individual control.”

Benhamin Ben-Baruch, a market-intelligence consultant based in Michigan, responded that terror acts will be motivated by the same root causes of today. “It will be those who are struggling against the losses of freedom, privacy, autonomy, etc., who lack the resources to struggle in conventional ways and who will resort to whatever methods are available to them in asymmetrical wars,” he wrote. “Ironically, increasing reliance on vulnerable technologies will make cyber attacks increasingly attractive to the relatively powerless.”

Howard Finberg, director of interactive media for the Poynter Institute, wrote, “The new terrorism might be cyber-terrorism. This will be a rebellion against the mass culture of technology.”

Suely Fragoso, a professor at Unisinos in Brazil, responded, “I do not think that people will commit acts of terror or violence in protest against technology, directly, but against social, political, and economic conditions that bind the development of technologies as well as other human endeavours.”

And Peter Kim of Forrester Research sees a 2020 organized online. “WTO-type protests grow in scale and scope,” he wrote, “driven by the increasing economic stratification in society. Some fringe groups or even cults emerge that isolate themselves from society, using virtual private networks.”

Some respondents point out that acts of civil disobedience have value.

[book]

Some respondents welcomed a questioning of the advance of technology. “We need some strong dissenting voices about the impact of this technology in our lives,” wrote Denzil Meyers of Widgetwonder. “So far, it’s been mostly the promise of a cure-all, just like the past ‘Industrial Revolution.’“

Wladyslaw Majewski of OSI CompuTrain and the Poland chapter of the Internet Society, pointed out the potential for acts of terror perpetrated by controlling groups. “There is no real data that would justify the connection of acts of terror with people refusing to use communication technologies,” he wrote. “In fact exact opposite is a real danger – governments, corporations, and privileged circles eager to use new technologies to facilitate terror and deprive people from their rights.”

Andy Williamson of Wairua Consulting and a member of the New Zealand government’s Digital Strategy Advisory Group responded, “Remember that the original Luddites did not want to destroy technology because they did not understand it. They did so because they saw that it simply made a small group rich and a large group poorer and even less able to control their lives. If ICTs continue to be used for personal gain and by powerful governments and corporations to control freedoms and limit opportunities for the majority, then the above is not only likely, but highly necessary. Not quite storming the Winter Palace, but certainly information terrorism on Mountain View and Redmond!”

A number of respondents cast this as a battle between ‘old’ and ‘new’ values.

There were differences of opinion over whether current conflicts between traditionally conservative cultural groups and those with capitalistic, consumer-driven economies are actually a war over the advancement of technology. “The most important resistance to technology comes from those who oppose change for ideological, religious, economic or political reasons,” wrote Gary Chapman, director of the 21st Century Project at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. “These are the forces that have used government power to stifle progress in many times and places and could do so again.”

[kind of violence]

Paul Saffo, forecaster and director of The Institute for the Future, responded, “The question is how many such attacks will happen and how large they will be. While anti-technology activists may capture our imagination, the risk will come from fundamentalists generally, and religiously-motivated eschatological terrorists in particular. But the good news is that this trend will gradually burn itself. The Caliphate will not return, the apocalypse will not happen, and eventually world populations will come to their senses. Even lone terrorists must swim in a social sea, and the sea will become less tolerant of their existence. Notions of ‘super-empowered individuals’ terrify us today in the same way that H-bombs terrified our parents and grandparents half a century ago. But if we are lucky, they will, like H-bombs, remain more looming threat than actual disaster.”

Mike Kent, a professor of social policy at Murdoch University in Australia, responded, “It seems more likely to me that existing terror groups will attack the system from within, rather than without.”

Whether technological process moves quickly or slowly, some believe anti-technology violence won’t add up to an enormous problem.

IT policy maker Alan Inouye, formerly with the Computer Science and Telecommunications Board of the U.S. National Research Council, predicts that technological change won’t inspire the radical differences that might lead to violence. “While I expect continuing advances in our ability to harness IT for societal good (and bad), I don’t expect such dramatic changes in daily life,” he wrote. “The past 15 years – 1990 to 2005 – represented the diffusion of the Internet and cell phones to the general population. The preceding 15 years – 1975-1990 – represented the diffusion of the PC to the general population. Although the advances in the past 30 years have been remarkable, much of daily life is not so different. Maybe we will finally see the long-threatened convergence of information technologies and, as a consequence, vastly improved capabilities. But I am not so convinced.”

Glen Ricart, formerly of DARPA and currently with Price Waterhouse Coopers and the Internet Society Board of Trustees, predicts more breakthroughs, but says they will appear incrementally and not cause conflict. “I doubt there will be a new digital divide along the lines postulated here,” he responded. “I think there will be a continuum of technology use that can be measured as ‘face time’ versus ‘screen time.’ I think there are good reasons that ‘screen time’ will never overtake ‘face time.’ Well, maybe one exception. There will probably be some pathological cases of being addicted to virtual realities. Interestingly enough, this may be caused by spending too much time in youth interacting with games (and perfecting that genre) instead of interacting with other kids (and perfecting the pleasures of inter-personal relationships in the real world). By the way, in 2020, it may no longer be ‘screens’ with which we interact. What I mean by ‘screen time’ in 2020 is time spent thinking about and interacting with artificially-generated stimuli. Human-to-human non-mediated interaction counts as ‘face time’ even if you do it with a telephone or video wall.”

It’s expected that people will resist too much connection in various ways.

“Off the grid” was originally a phrase constructed to refer to the idea of living in a space that is not tied to the nation’s power grid. The definition has been sliding toward a more generalized concept of living an un-networked life that excludes the use of items such as televisions, cell phones. Some people even aim to live a life that can’t be tracked and logged onto databases by the government and corporations. Some survey respondents see resistance to connection as a possible trend. The reason for such resistance was articulated by Charlie Breindahl, a professor at the University of Copenhagen: “By 2020 every citizen of the world will be as closely monitored as the Palestinians are in the Gaza Strip today. No one will be able to get off the grid.”

Brian Nakamoto of Everyone.net predicted, “Living off the grid (comfortably) will be extremely difficult in 2020.” Barry Chudakov, principal partner of The Chudakov Company, agreed. “My sense is that technology will become like skin – so common that we forget we’re in it,” he wrote. “Devices will be infused with some manner of intelligence and fit into all manner of objects, from clothing to prescriptions. So it won’t be a simple thing to live ‘off the grid’ – unless, of course, you’re a Unabomber type. But those types are rare and live only at the antisocial fringe.”

“I’m already familiar with several colleagues who have chosen to only pay cash for items and to eschew cellular telephones because they can be tracked,” wrote William Kearns of the University of South Florida. “Being ‘always connected’ is not healthy, any more than it’s healthy to be always awake. It’s also not particularly good for your survival to be out of touch with your surroundings (the wolf may be outside the door). Specialized intelligent filters will become popular to self-select information for people and filter out adware, pop-ups, nuisance mail, and everything we haven’t thought of yet. The motivation will be to reduce the annoyance factor with dealing with the mountain of detritus that passes for information on the network. Humans do a remarkably good job of making decisions without having access to all the facts. We should revel in that ability.”

Martin Kwapinski of FirstGov wrote, “There will absolutely be those who attempt to live ‘off the grid.’ The changes these technologies are bringing are massive, difficult to conceive and terrifying to many.” Mitchell Kam of Willamette University responded, “Most will just choose to live in isolation and in separate societies.” Judy Laing of Southern California Public Radio responded, “They’ll probably pick up where the ’60s left off; their communities will be the resorts of their time.”

Walter Broadbent, vice president of The Broadbent Group, has a solution for that. “Allowing/encouraging others to create a place for themselves off the grid is a viable solution for them,” he responded. “We can use the power and influence of the Web to support others and encourage them to participate.”

‘Transparent, humane’ technology is most likely to be accepted.

Some respondents said innovations in interface design will make technology more approachable and accessible for the mass population, thus making it less likely to inspire protests of any sort.

Frederic Litto of the University of Sao Paulo responded, “In 1994, an international conference in London on resistance to new technologies concluded that: (1) a certain amount of such resistance is useful to society because it serves as a ‘rein’ to control possible excesses in the use of the new technology; (2) such resistance is frequently the product of bad design of the interface between the user and the system (like the first automobiles, which required every driver to know how to fix his own auto, because there were no mechanics on every street-corner – today, the interface design has improved, and the whole auto is a ‘black box’ to every driver). Just as those who used to throw stones at ‘horseless carriages’ are no longer with us, so, too, the crazies who protest against very useful and environmentally-friendly technologies, will eventually be drawn to other pursuits.”

Martin Murphy, an IT consultant for the City of New York, wrote, “In 2020 I will be 75 years old. Many of the ‘Baby-Boomers’ will be over 70 years old. This large group of people may indeed be sick of the constant intrusion of technology and nostalgic for a more human-centered time. If they get together with young, philosophically-inspired anti-technology activists, things could get interesting. The trick will be to make the technology transparent and humane.”