Some evidence about relationships has been alarming.

Robert Putnam argued in 2000 that people are seeing friends and relatives much less than they were in the mid-1960s. For example, family picnics decreased by 60% between 1975 and 1999, and card playing went down from an average of 16 times per year in 1981, to 8 times per year in 1999.

Yet evidence from the Social Ties survey show that the situation is not so dire. For one thing, we did not ask about picnics; we asked directly about social relations. This leads to a focus on social networks, whomever they include and wherever they are located. For example, friends and relatives are now spatially dispersed rather than concentrated in neighborhoods. The difficulty of traveling to get together may explain why picnics have declined as a way for friends and relatives to meet. Yet other ways of interacting have flourished, on- and offline.

Americans have an average of more than 200 relationships with friends, relatives, and acquaintances. The Social Ties survey could not gather information about all these relationships, but it was able to get information about a large number of Americans’ important ties — all of those relationships that are more than just acquaintances. Specifically, the Social Ties survey asked about two types of ties:

- Core Ties: These are the people in Americans’ social networks with whom they have very close relationships — the people to whom Americans turn to discuss important matters, with whom they are in frequent contact, or from whom they seek help. This approach captures three key dimensions of relationship strength — emotional intimacy, contact, and the availability of social network capital.

- Significant Ties: These are the people outside that ring of “core ties” in Americans’ social networks, who are somewhat closely connected. They are the ones with whom Americans discuss important matters to a lesser extent, are in less frequent contact, and are less apt to seek help. They may do some or all of these things, but not as extensively. Nevertheless, although significant ties are weaker than core ties, they are more than acquaintances and they can become important players at times as people access their networks to get help or advice.

By probing these two types of relationships, the Social Ties survey provides novel information about the social networks of a sizable proportion of Americans. This information helps us develop a snapshot of what these networks look like.

Social networks are flourishing in America.

Despite concerns that Americans are living lonely and isolated lives, results from the Social Ties survey show that Americans maintain a sizable number of relationships with people who are more than just acquaintances. These relationships include both very close core ties and somewhat close significant ties.

- If each American were sorted in rank order according to the number of their core ties, the American in the middle would know about 15 people. This statistical median reveals that half of all Americans have at least 15 very close core ties. The mean number (average) is 23 core ties.7

- Americans have a median of 16 somewhat close significant ties in their social networks. The mean number is 27 significant ties.

- Americans have a median of 35 core and significant ties in their networks that represent people who are more than just acquaintances. (The mean is 50 total ties.)

There are important statistical considerations when examining these survey results.

The differences between the median and mean values indicate that a sizable number of Americans report having large networks. For statistical reasons, these “outliers” have a disproportionate influence on the analysis that follows. To deal with this issue, we divide core and significant ties into thirds: small, medium, and large.

- Core ties are divided into small (0 to 10 ties), medium (11 to 22 ties), and large (more than 22 ties).

- Significant ties also are divided into small (0 to 10 ties), medium (11 to 26 ties), and large (more than 26 ties).

The Pew Social Ties survey also shows much different numbers of core ties than the much smaller mean of 2.1 core ties found by McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Brashears in the U.S. General Social Survey of 2004, which itself was a reduction from the 2.9 found by Marsden in the 1985 General Social Survey.8 The reason is that these other studies used only one criterion for identifying core ties: confidants with whom important matters are discussed.

Yet, there is more to being “very close” to a person than being a confidant discussing important matters. Having frequent intimate contact — whether in person or online — and providing help to each other clearly play roles. Hence, we used “people you are very close to” as the key question and prompted survey respondents to tell us about people very close to them, those with whom they are in frequent contact or from whom they get substantial help, as well as those with whom they discuss important matters. The discrepancy is also due to the fact that we asked only about close ties outside of the home, while the other surveys allowed people to include people inside the home, such as spouses.

The substantial numbers of core and significant ties show that most Americans are not isolated. But are these results accurate, given that they are estimates given during phone interviews? We are reassured that two earlier North American studies showed similar results — Claude Fischer’s study in northern California that took place in the late 1970s, and Wellman and Wortley’s research in southern Ontario that took place about a decade later. Moreover, similar numbers show up in three recent studies in France, Germany, and Iran.9

Larger social networks include proportionally more friends than immediate family.

Survey respondents told us the number of their ties that are immediate family — parents, adult children, brothers and sisters, and the corresponding in-laws — as well as about other family members, workmates, neighbors, and friends. These numbers were then added together to give the total number core ties and significant ties for each respondent.

Overall, among core ties, a mean of 35% are immediate family, 19% are other family, 12% are workmates, 9% are neighbors, and 24% are friends. Significant ties include a smaller percentage of immediate family and a higher percentage of workmates and neighbors: a mean of 21% are immediate family, 18% are other family, 19% are workmates, 12% are neighbors, and 24% are friends.

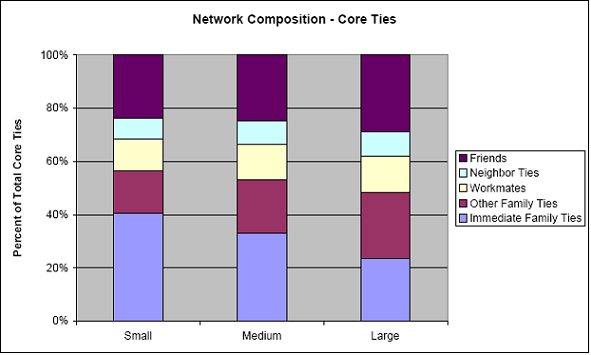

We found that as the number of core ties grows, the percentage of those ties that represents immediate family members — parents, adult children, brothers, and sisters, and inlaws — becomes smaller. At the same time, the percentage that represents friends and other family members becomes larger. (See Figure 1) For example, people with small numbers of core ties report that 41% of their core ties are immediate family members, while people with large numbers of core ties report that about 24% of their core ties are with immediate family members. By contrast, people with small numbers of core ties report that 16% of their core ties are other family members and 24% are friends, while people with large numbers of core ties report that 25% of their core ties are other family members and 29% are with friends.

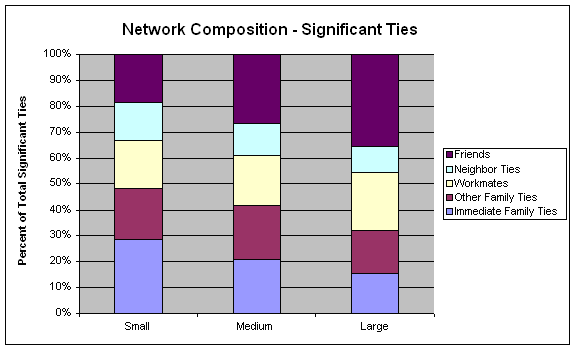

As the number of significant ties becomes larger, the percentage of these ties that are immediate family members becomes smaller. At the same time, the percentage that represents friends becomes larger. (See Figure 2) People with small numbers of significant ties report that 28% of these ties are immediate family, while people with large numbers of significant ties report that about 16% of these ties are immediate family. By contrast, people with small numbers of significant ties report that 18% of these ties are friends, while people with large numbers of significant ties report that 35% of these ties are friends.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Internet users have more significant ties than non-users.

Internet users have about the same number of core ties as internet non-users, a median of 15.10 However, internet users have larger numbers of significant ties. Where non-users have a median of 15 significant ties, internet users have a median of 18 significant ties. Moreover, as described in Part 5, internet users communicate with more of their core ties as well as their significant ties — not only by email but also in person and by phone.

There are few significant demographic differences among those with different size networks.

People with many core ties tend to be female, older, and better educated. People with many significant ties tend to be better educated and to work in professional occupations. More information is presented in the Methodology section at the end of this report.