Close to two-thirds of Americans now go online to access the Internet.

- 63% of Americans now go online — last measured in our August 2003 survey.

- That amounts to 47% growth in the U.S. adult population using the Internet, from 86 million in March 2000 to 126 million in August 2003.

- 52% of Internet users go online on a typical day, as of August 2003. That figure amounts to 66 million people and has grown from 52 million who were online during a typical day in March 2000.

- 87% of U.S. Internet users said they have access at home, and 48% said they have access at work in our August survey.

- 25% said they use the Internet at times from some place other than home or work in our March–May 2003 survey.

- 31% of Internet users who go online from home have broadband as of August 2003.

- African-Americans and seniors are among least likely to go online.

- Internet use is strongly tied to higher levels of education and household income.

- Parents are more likely than non-parents to use the Internet.

With fewer new users logging on, the Internet population matures

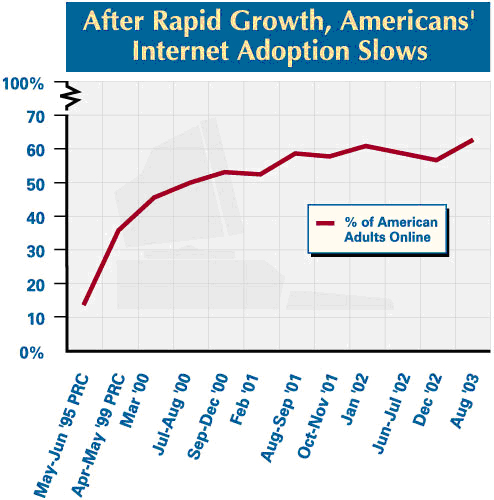

When the Pew Internet & American Life Project first started measuring Internet usage in March 2000, 46% of American adults (roughly 86 million people) had logged on to access the Web or to send and receive email. That portion was more than three times the size of the online population documented by the Pew Research Center for The People & The Press in 1995 — just 14% of Americans were identified as “online users” at that time.13

Internet use proliferated through the late 1990s and into 2000. By August 2003, the Pew Internet Project’s survey found that 63% of American adults were online. Taking the overall growth of the U.S. population into account, that represented an estimated 126 million people, up 47% from the 86 million who were online in our first survey in March 2000.

However, most of that growth occurred over the course of 2000 and slowed dramatically in the fall of 2001 and thereafter, suggesting that the dramatic growth of Web use in America had tapered off. As the Internet increasingly became a part of everyday life for Americans, there were no longer droves of new users rushing online. Instead, small fluctuations in the overall population indicated that as new people came online, others were dropping off. This flattening trend appeared across all demographic groups and not just among those who were early adopters and have reached high penetration levels, such as upper-income and upper-education groups.

The same slowing has also been evident among those who use the Internet on a typical day. While these “daily” users grew by over 10 million Americans between March 2000 and December 2002, the proportion of all Internet users who go online on an average day remained slightly under 3 in 5 throughout 2002.

The percentage of Internet users who said they went online “yesterday” in our surveys is also referred to as those who go online on a “typical day.”

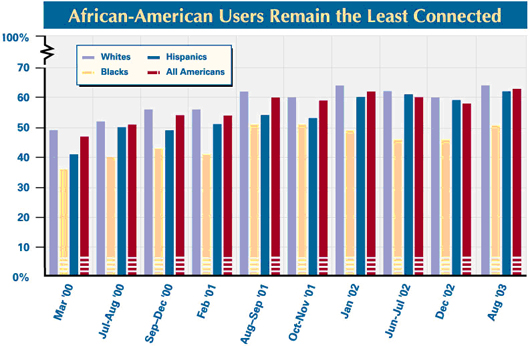

Over time, levels of Internet experience have shifted as well. In March 2000, 18% of Internet users had been online for 6 months or less, 21% had been online for 1 year, 33% for 2-3 years, and 28% had used the Internet for more than 3 years. In contrast, our December 2002 data revealed that the large majority of online Americans had reached “veteran” status; just 1% had used the Internet for less than a year, 6% for about 1 year, 23% for 2-3 years, and 68% had been online for more than 3 years. And most recently, when we surveyed in August 2003, 2% had used the Internet for less than a year, 5% for about 1 year, 19% for 2-3 years and 74% had been online for more than 3 years.

The way people connect to the Internet has also evolved. Though most online Americans still log on from home (87% of U.S. Internet users had access at home and 48% had access at work in our August 2003 survey), about a third are doing so with high-speed connections. That translates to roughly 39 million American adults who now have some type of high-speed access at home (as of August 2003). In comparison, 25% of home Internet users said they had high-speed connections in our December 2002 survey, and just 6% of home Internet users had broadband when we first started asking about it in June 2000.

During the formative stages of Web use, men were much more prominent in the online world than women. According to Pew Research Center from 1995, 18% of adult men were online in America, while only 10% of adult women were Internet users. Women have since reached parity within the population of Internet users. In August of this year, 65% of men and 61% of women were online. Since there are more women in the United States than men, this meant that the Internet population was about 51% female. However, male Internet users have been more likely than online women to access the Web on a typical day.

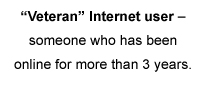

Change has also occurred in the racial and ethnic composition of the Internet population. Whites predominated in the mid-1990s, minorities saw high growth rates at the turn of the century, and the growth in all groups slowed in 2002. Whites hit 63% for Internet penetration in January 2002, dipped somewhat in the months after that, then hit 64% in August 2003. English-speaking Hispanic users, who demonstrated marked growth, reached 61% in September 2002 and then 62% in August 2003.14 Overall, African-Americans have also exhibited considerable growth over the past 3 years, but their penetration rates still remain well below whites and Hispanics. In December of 2002 45% of African-Americans said they were online, and in August 2003, 51% said so.

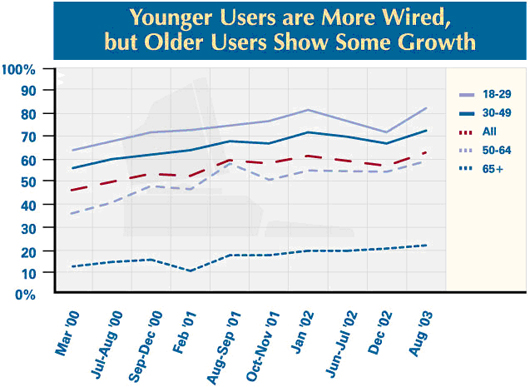

When it comes to age, those who are 18-29 have been among the most wired demographic groups from the onset of Internet growth. By March 2000 when we began our surveys, 64% of these young adults were already online, which compared to 56% of 30- to 49-year olds, 36% of the 50-64 age group, and 12% of those aged 65 and over. Internet use among young adults blossomed over the next 2 years and reached 80% penetration in January of 2002. It then contracted back to 72% by December of that year, but rose back up to 83% in August 2003. The 30-49 age group also leveled off over 2002, so that 67% were online in December. But by August of this year, 73% of 30- to 49-year olds said they used the Internet. Similarly, the 50- to 64-year olds stabilized at exactly 55% for all but one survey period during 2002 but then grew to 59% in our August survey. The least wired age group, those 65 and over, has come online slowly but steadily since 2000, and showed only negligible growth over the course of 2002 and 2003 — 20% of seniors were online in December 2002, and 22% reported use of the Internet in our August 2003 survey.

Other demographics confirm the slowdown in Internet growth.

The data from the various education and income groups further confirms the slowed growth of the online population in 2002. Of particular note was a decline in the number of people with less than a high school degree who are online. Thirty-one percent said they were online in our January 2002 survey, while just 19% said they were Internet users in December 2002. By our August 2003 survey, those with less than a high school degree had gone back up to 26%, but that is still less than half the percentage of high school graduates who said they use the Internet.

We have repeatedly found in our research that those with higher income and education levels are much more likely to be Internet users. As was noted in our “Ever-Shifting Internet Population” report15, when income is considered independent of all other factors, having a household income above $50,000 annually predicts Internet use. Similarly, a high level of education was also shown to be a strong predictor of Internet use.

Parents have time and again been more likely to access the Internet than non-parents; 55% of parents and 42% of non-parents said they were online in our March 2000 survey compared to 75% of parents and 57% of non-parents who reported usage in August 2003.

Almost all who are online have sent or read email.

- 93% of Internet users have sent or read email according to our December 2002 survey.

- That amounts to 31% growth from 78 million in March 2000 to 102 million in December 2002.

- African-Americans are among the least likely to say they use email.

- More in upper education and income groups use email than those in lower socio-economic groups.

- High-speed connections and experience online matter most when looking at Internet users’ frequency of emailing.

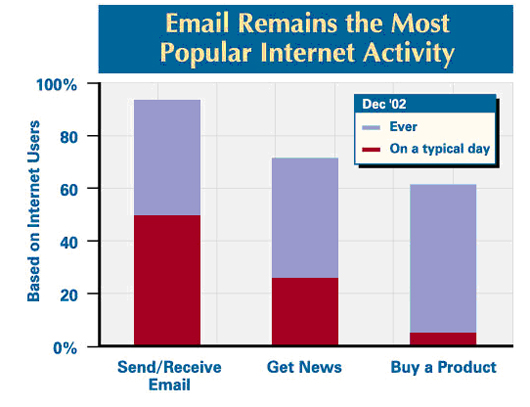

Email remains the most popular Internet activity

Sending and reading email is by far the single most popular use of the Internet. More than nine out of ten Internet users, or approximately 102 million Americans, use email, and half of the online population is sending or reading email on an average day. Learning to use email is often the inaugural activity for new users and is often the impetus for non-users to take the leap and come online.

The use of email has become such a seamless part of everyday life for Americans that it seems hard to imagine life without it. Having an email address is the norm, and checking one’s email inbox has become almost as routine as stepping out one’s front door to check for “snail” mail.

When the Pew Research Center polled Americans in 1995, only 72% of online Americans said they had used email, but 5 years later, in our March 2000 survey, that number had leapt to 91%. While the percentage of Internet users who had used email did not change dramatically over the next 3 years, the online population continued to grow, and the number of emailers swelled by roughly 24 million people between 2000 and 2002. The number of online Americans who send or read email on a typical day grew from 45 million in March 2000 to 54 million in December 2002.

We have documented the power and impact of email in our reports. For example, we have found that the use of email reinforces Internet users’ social connectedness to family and friends; the longer a user is online, the more likely she is to cite the positive effect email has on her social ties.16 Email has also become an effective tool at the workplace; the vast majority of work emailers say it helps them communicate better on the job.17 Further, we have reported that email has helped citizens communicate more efficiently with their local government officials; among other benefits, email is helping officials better understand their constituents and helping to facilitate public debate.18

In the first report the project issued, “Tracking Online Life: How Women Use the Internet to Cultivate Relationships with Family and Friends,” we noted that the social impact of email was particularly pronounced among women. Women were much more likely than men to say that email had played a role in improving relationships, and they were also more likely to say that they looked forward to checking their email. That positive attitude toward email has been reflected in female Internet users’ slightly more aggressive uptake of email over the course of our research. In December 2002, for example, 95% of female Internet users said they used email, while only 90% of male Internet users said so. However, men and women were equally as likely to say they receive or send email on a typical day.

African-American Internet users have been less likely than white users to say they use email. In our June–July 2002 survey, for example, 87% of online African-Americans said they used email, compared to 93% of online whites. This trend is even more apparent on any given day online; 39% of African-American users were emailing on a typical day in November 2002, while 54% of white users were doing so.

Email usage by online English-speaking Hispanics has also differed most noticeably on a typical day. In November 2002, for instance, 94% of Hispanics had used email compared to 93% of whites. However, on a typical day during that survey period, 39% of online Hispanics were sending and reading email, while 54% of white users were doing so.

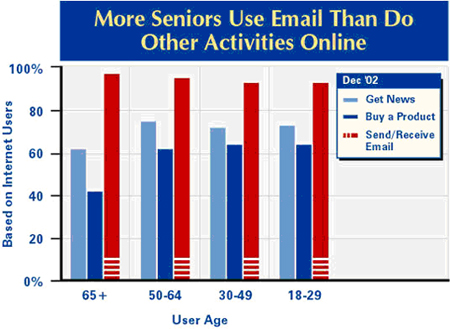

Even though many other online activities hold limited appeal to senior citizens, email has been completely embraced by Internet users over the age of 65. Often encouraged by younger family members to start using email, wired seniors can be fervent message senders. In our surveys, their use of email has typically held steady or marginally surpassed the overall trend of all users. This is also true of seniors who use email on any given day.

Other demographics

Over time, education and income levels have become less important factors distinguishing heavy email users from others. For example, while 39% of high school graduates were sending email on a typical day in December 2002, 61% of college graduates were doing so. Thirty-seven percent of users living in households earning less than $30,000 per year sent or read email on a typical day last December, compared to 58% of users living in households earning $75,000 or more.

Experience online has also come to matter most when looking at the frequency of email use — 28% of those who have been online for 1 year or less sent or read email on a typical day in December while 49% of those with 4-5 years of experience did so.

High-speed Internet connections appear to influence the rate of email use as well; broadband users send and receive email more frequently than dial-up users. In December 2002, 70% of home broadband users were sending or reading email on a typical day while just 47% of dial-up users were doing so.

For more information on email use, please visit the following Pew Internet & American Life Project Reports:

- Email at Work: Few feel overwhelmed and most are pleased with the way email helps them do their jobs. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2002/Email-at-work.aspx

- Spam: How it is hurting email and degrading life on the Internet: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2003/Spam-How-it-is-hurting-email-and-degrading-life-on-the-Internet.aspx

About half of Internet users send Instant Messages.

- 46% of online Americans have sent instant messages according to our June–July 2002 survey.

- That represents growth of 33% from 39 million in March 2000, to 52 million in June-July 2002.

- Young adults and Internet veterans are among the most fervent IM users. (Our special study of teenagers showed they are the most fervent IM users of all.)19

- There are more IM users in lower education and income groups than in many other online activities.

- A high proportion of online Hispanics are IM users.

- Those with broadband access and those with high levels of experience online are more likely to have used IM compared to dial-up users and those with less experience online.

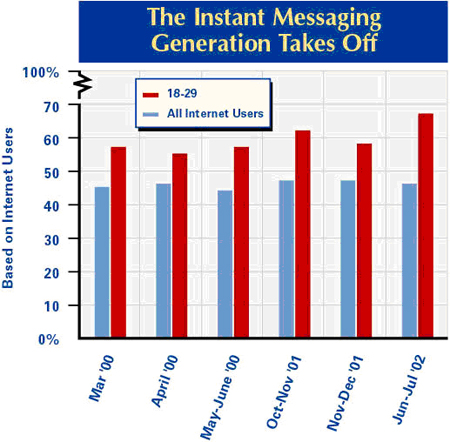

Instant messaging programs allow Internet users to have real-time conversations with other “buddies” who are online at the same time. While instant messaging (also referred to as IM) has overwhelmingly been the province of teenagers, nearly half of all American adults who are online have sent an instant message at one time or another. When we last asked about this activity in the summer of 2002, about 52 million people (46% of all Internet users) had tried some type of instant messaging and about 10 million (11% of Internet users) were exchanging IMs on any given day online. That is up from 39 million (45% of Internet users) who had used IM in March 2000 and 10 million (12% of Internet users) who used it on a typical day. Comparatively, when we interviewed teenagers in November and December 2000, three-quarters (74%) had used IM and a third (35%) said they did so every day.

Instant messaging is far from outpacing email, but we have repeatedly found that Internet users are almost twice as likely to use IM as they are to take part in a chat room. Furthermore, they are three times as likely to use IM on a typical day compared to chatting.

Instant messaging has appealed similarly to both men and women as an online communication tool. Overall, IM is slightly more common among women than men. However, men are more likely than women to be IM-ing on any given day.

Similar to the racial trends in chatting online, IM-ing is especially popular among English-speaking Hispanic users. More often than not, Hispanics have been the most enthusiastic users of IM compared to African-American and white users. In the summer of 2002, 64% of English-speaking Hispanic users said they had used IM, while only 46% of whites and blacks reported doing so. The difference was even more pronounced for those who were using IM on a typical day (23% of English-speaking Hispanics, 10% of whites, and 7% of blacks).20

In keeping with our findings on teens’ disproportionately high usage of IM, the greatest variations among instant messaging use are most evident when comparing activity levels across different age groups. Considering that some of the teens we interviewed in 2000 are now young adults, it is not surprising to see that by the summer of 2002, 18- to 29-year-olds were by far the most enthusiastic adult users of IM.

Other Demographics

Because instant messaging has been such a youth-oriented activity, it is understandable that there are higher proportions of IM users in the lower education and income groups. When we last asked about IM in 2002, half of those with a high school education or less had used IM, while only 39% of those with a college degree had done so. Similarly, 54% of those who had a household income below $30,000 used IM, compared to 44% of those with income levels of $75,000 and above.

We have repeatedly found that when it comes to adults, instant messaging is an activity where experience matters. Our 2002 data showed that those with 4 or more years of experience were almost three times as likely to have used IM on an average day compared to those with only 1 year (or less) of experience online. Broadband users were somewhat more ardent instant messagers than dial-up users; 16% of them used IM on a typical day, while 12% with dial-up connections did so.

For more information on Instant Messaging and Youth, please see the Instant Messaging section of the Pew Internet Project report:

-

Teenage Life Online: The rise of the Instant Message generation and the Internet’s impact on friendships and family relationships https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2001/Teenage-Life-Online.aspx

About a quarter of Internet users have taken part in chat rooms or online discussions.

- 25% of users have participated in chat rooms or online discussions, according to our latest figures from a survey in June–July 2002.

- The number of people who have used chat rooms or online discussions has grown a modest 21% — from 24 million in March 2000, to 29 million in June-July 2002.

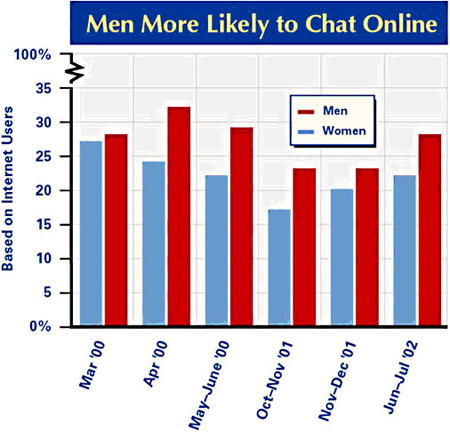

- Men are more likely than women to have used chat rooms or online discussions.

- Chat rooms and online discussions are most popular among young adults, and minority Internet users.

- Relatively high proportions of those in lower income groups and those with lesser educational attainment have used chat rooms and online discussions.

- Compared to IM, a very small percentage of Internet users take part in chat rooms or online discussions on a typical day online.

Participation in chat rooms and online discussions plateaus

Engaging in chat rooms or online discussions has grown minimally over the course of our research, but more than a quarter of Internet users — roughly 29 million Americans — said they had used this mode of communication the last time we polled this question in the summer of 2002. That compares to 52 million who said they used instant messaging during that period and 106 million who used email. The proportion of Internet users who were taking their discussions online was actually slightly higher in March 2000 (28%) than in 2002 (25%), but because the total online population has grown, the estimated number of people doing this activity grew by approximately five million Americans in that time (from 24 million to 29 million).

A relatively small proportion of Internet users take part in chat rooms or online discussions on a typical day. Just 4% reported doing so in the summer of 2002, compared to 11% who were sending instant messages and 46% who were sending and reading email on an average day during that period. Overall, the estimated number of users taking their discussions online on a typical day grew from 4 million to 5 million between 2000 and 2002.

Online discussions can take place in a variety of different settings and the topics that people choose to engage range from lighthearted gossip to serious elicitations about severe medical conditions. Aside from social and health-related issues, Americans will discuss just about anything online; we have found that pop culture, hobbies, politics and religion are just a few of the many things people bond over and debate about online. In addition, many Web sites now offer online help and consultation via chat technologies as a standard feature. For example, users can readily ask questions of librarians, nurses, and computer experts or participate in live discussions with celebrities via the Internet.

The archivable nature of online discussions makes them a valuable resource for documenting public reaction to significant historical events. Following the events of September 11th, many Americans turned to chat rooms as a place to discuss the tragedy. The transcripts of these exchanges provide a powerful record — containing personal stories, opinions, and reflections — of the way people responded and interacted after this traumatic period.21

However, this potential for electronic documentation also causes some users to shy away from sharing their thoughts online for fear that their comments could be traced or otherwise be used against them. Others feel that the relative anonymity of chat rooms and online discussions provides safe harbor to discuss issues that they may not feel comfortable talking about in face-to-face interactions.

In contrast to what we have found with email and instant messaging, men have been somewhat more likely than women to participate in chat rooms or online discussions. In a 2002 survey, 28% of online men had conversed online, while 22% of online women said they had done so. On a typical day, men and women have become equally likely to chat and engage in online discussions —4% of each group did so in 2002.

Over time, there has been evidence that online English-speaking Hispanics and online African-Americans are more likely to have participated in online discussions and chat rooms compared to online whites. In the June–July 2002 survey, 40% of English-speaking Hispanic users had engaged in online conversations, while 35% of African-American users and only 22% of white users had done so.22

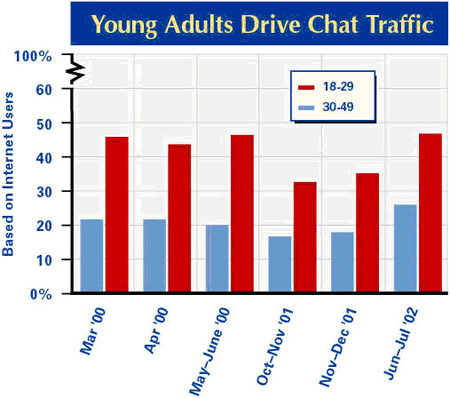

As is the case with instant messaging, teens and young adults clearly occupy most of the traffic to chat rooms and other online discussions. In our research on teens in mid-2001, we found that 55% of online teens had visited a chat room (they were not asked about participation in an online discussion other than chat rooms). In our 2002 research on adult Internet users, 47% of 18- to 29-year-olds said they communicated via online discussions and chat, but less than half as many, only 21% of the next age bracket (30- to 49-year-olds) said they had done this. That age gap has been consistently reproduced every time we ask this question, with users over the age of 50 being the least likely to use these communication tools.

Other demographics

Those with the least education and lowest income levels are among the most likely to have participated in online conversations. In the summer of 2002, 27% of Internet users with high school educations had participated in chat rooms or online discussions, while just 17% of college graduates reported doing so. During the same survey, 39% of Internet users in households earning under $30,000 per year had tried chatting online, but just 19% of those in households earning $75,000 or more had done this.

Connection speed seems to affect the frequency with which a user is likely to converse online, but broadband users are generally no more likely to have tried chat or online discussions than dial-up users.

Another finding that may be linked to age is that users with less experience online have become more likely to use these communication features. In addition, single online parents are more likely to say they have had conversations on the Internet than married parents who are online. Likewise, Internet users in college are twice as likely to have online discussions compared to the overall online population.23