This article was originally published in the Fall 2017 edition of Issues in Science and Technology magazine.

For many years, the scientific community has been wondering—and often worrying—about the extent to which the public trusts science. Some observers have warned of a “war on science,” and recently some have expressed concern about the rise of populist antagonism to the influence of experts.

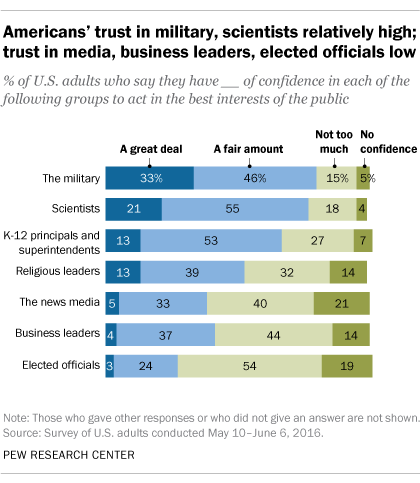

But public confidence in the scientific community appears to be relatively strong, according to a nationally representative survey of adults in the United States by the Pew Research Center in 2016. Furthermore, scientists are the only group among the 13 institutions covered in the General Social Survey conducted by the National Opinion Research Center where public confidence has remained stable since the 1970s. However, this favorable attitude is somewhat tepid. Only four in 10 people reported a great deal of confidence in the scientific community.

A series of other Pew Research Center studies, however, have revealed that public trust in scientists in matters connected with childhood vaccines, climate change, and genetically modified (GM) foods is more varied. Overall, many people hold skeptical views of climate scientists and GM food scientists; a larger share express trust in medical scientists, but there, too, many express what survey analysts call a “soft” positive rather than a strongly positive view.

There are, of course, important differences in opinions about scientists in each of these domains. For example, people’s views about climate scientists vary strongly depending on their political orientation, consistent with more than a decade of partisan division over this issue. But public views about GM food scientists and medical scientists are not strongly divided along political lines. Instead, views about GM food issues connect with people’s concerns about the relationship between food and health; most people are skeptical of scientists working on GM food issues and are deeply skeptical of information from food industry leaders on this issue. On the other hand, older adults, people who care more about childhood vaccine issues, and those who know more about science are, generally, more trusting of medical scientists working on childhood vaccine issues than are other people.

It is important to keep in mind that public beliefs about science and scientists aren’t necessarily indicators of trust, per se. One example involves public support for the products of scientific and technological innovation. A Pew Research Center survey found that about two-thirds of people see the effects of science on society as mostly positive, which is consistent with some 35 years of data from the General Social Survey. Looking at the components of trust in science across these three scientific areas— vaccines, climate change, and GM food— two patterns stand out. First, public trust in scientists is stronger, by comparison, than it is for several other groups in society. For example, many more people report trust in information from medical scientists, climate scientists, and GM food scientists than information from industry leaders, the news media, and elected officials. On the other hand, no more than about half of people hold strongly trusting views of scientists in any of these domains. For example, only 47% of people say that medical scientists understand the health effects of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine “very well.” Some 43% hold soft positive views of medical understanding about the MMR vaccine, saying medical scientists understand this issue “fairly well.”

The scientific enterprise is complex and so, too, is public opinion about science. The notion of trust itself has multiple dimensions. Public trust in scientists encompasses expectations about scientists’ actions, trust in scientists to be honest brokers of information, trust in scientific expertise and understanding, and trust in the motivations and influences operating on science research. Viewed through that lens, levels of public trust in science are quite varied, particularly across scientific domains.

Public confidence in scientists tends to be high compared with other groups

Public confidence in scientists is relatively strong compared with trust in other institutional groups. Only the military earns more confidence from the public. Still, people seem guarded. No more than a third of people report a “great deal” of confidence in any of these groups to act in the public interest. Overall, more people express positive than negative confidence in scientists, but a 55% majority express only a soft confidence in scientists to act in the public interest.

Scientists are seen as trustworthy communicators of science-relevant information compared with other groups

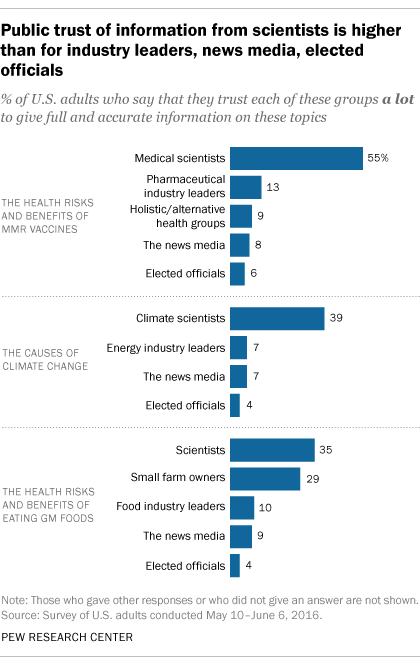

Public trust in scientists as sources of information is generally higher than it is for any of several other groups in society. For example, far more people trust medical scientists to provide full and accurate information about the health effects of childhood vaccines than they trust information from pharmaceutical industry leaders, the news media, or elected officials. The same pattern occurs for public trust in information from climate scientists and from GM food scientists.

But only a minority of people (39%) report “strong” trust in information from climate scientists. An equal share of adults say they have “some” trust in information from climate scientists, and about 22% are more skeptical, saying they do not trust information from climate scientists at all or not too much. The same pattern occurs for trust in information from GM food scientists.

Medical scientists are the most trusted of the three groups. Yet here, too, some 35% of adults have only soft trust in medical scientists to give full and accurate information about the effects of the MMR vaccine.

These findings suggest that the authority of scientists to speak on matters directly relevant to their expertise is often met with some skepticism.

There is limited public trust in the knowledge and understanding of scientists in areas directly relevant to their expertise

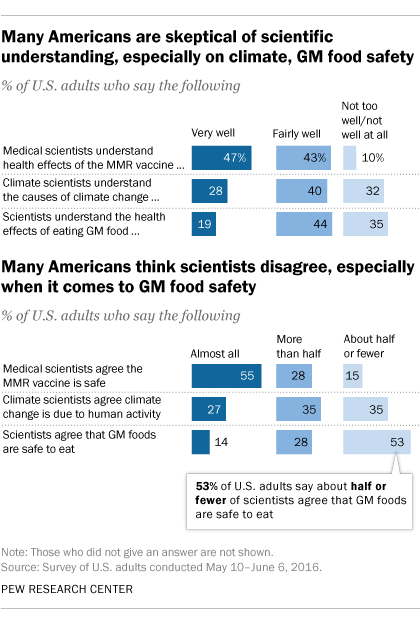

Minorities of people express strong trust in scientists’ understanding of the causes of climate change (28%) or the health effects of eating GM foods (19%), saying that scientists understand these matters “very well.” About half of people (47%) say the same about medical scientists’ understanding of the health effects of the MMR vaccine.

At least four in 10 people say that scientists understand each of these matters “fairly well.” A sizable share of people are skeptical of climate scientists’ and GM food scientists’ understanding about the causes of climate change and the health effects of GM foods, respectively, saying that scientists understand these matters “not too well” or “not at all well.”

Perceptions of scientific consensus align closely with people’s views of scientific understanding. From the public’s perspective, there is considerable scientific disagreement about all three of these issues, particularly GM foods.

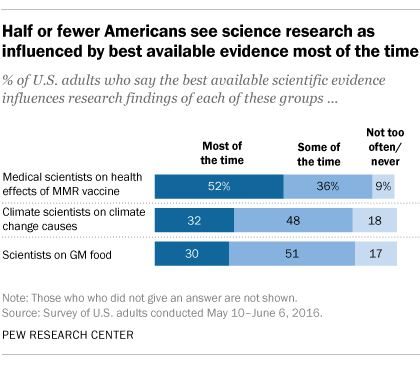

Half or fewer of people see the best available scientific evidence as routinely influencing scientific research in these domains

People hold mixed assessments about the influences operating on science research. About half of people (52%) say that the best available scientific evidence influences medical research on childhood vaccines “most of the time,” while some 36% say this occurs “some of the time” and another 9% say this seldom or never happens. There is even less public trust in research connected with climate change and GM foods; roughly three in 10 people say the best available scientific evidence influences climate research or GM food research “most of the time.”