Two-thirds of Americans use the internet to connect with government

Using the internet to interact with the government is hardly foreign to the American public. When the Pew Research Center took an early look at e-government applications in a 2003 survey, some 44% of Americans had used the internet to contact the government (for some reason other than a tax issue).9 A 2009 survey showed that 61% of Americans looked for information about government or did a transaction online with government.10

The figures released in this report are not comparable trend numbers to those previous surveys because the polls asked different questions about people’s online behaviors with government. However, the findings generally suggest more Americans are using the government’s online resources over time — no surprise given the growing numbers of online Americans over that time frame and the governments’ investment in online applications during that period.

Even though the questions asked in this survey also differ from past Pew Research Center surveys, the findings reveal that relatively high levels of Americans use the internet to transact with the government or gather information about government activities. In the past 12 months, about one-third of Americans used the internet or an app to access information or data provided by the three levels of government:

- 37% have used the internet or an app to get information or data about the federal government

- 34% have done so with respect to their state government

- 32% have used online tools to look for data or information about their local government

This comes to 49% of all adults who have done at least one of these three things with respect to using digital tools to find out about government or data it provides. Higher incomes households are more likely to have one of these three things. Two-thirds (66%) of those living in households with annual incomes over $75,000 have used the internet or apps for government information. (See the Appendix A for tables with detailed demographic breakouts for these and other survey results.)

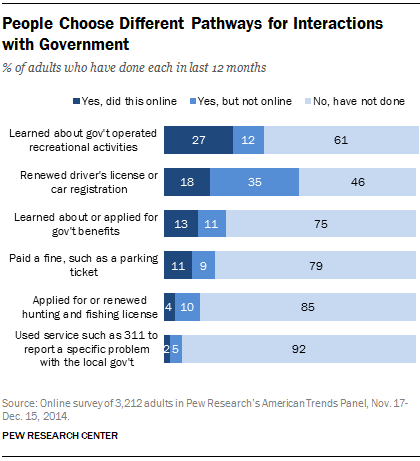

Americans use the internet often in dealing with various layers of government, but in many instances traditional offline methods dominate. Across six different activities people might go online to engage with the government, 46% of American adults did at least one of them online in the prior 12 months. Some 55% of Americans did at least one of the six listed activities offline in the prior 12 months.

Collecting the incidence of Americans who either went online or used an app connected to any level of government or did at least one of the six activities listed above online yields a sense of how many Americans in the prior 12 months have used the internet to connect with government. This number comes to 65%. That is, two-thirds of adults have, in the previous 12 months, used the internet to find out something about government, or the data it provides, whether they are thinking generally about their state, local, or federal government, or when asked about specific online activities.

Collecting the incidence of Americans who either went online or used an app connected to any level of government or did at least one of the six activities listed above online yields a sense of how many Americans in the prior 12 months have used the internet to connect with government. This number comes to 65%. That is, two-thirds of adults have, in the previous 12 months, used the internet to find out something about government, or the data it provides, whether they are thinking generally about their state, local, or federal government, or when asked about specific online activities.

Small numbers think governments are very effective in making data available

Although many Americans have used the internet or an app to search for government information or transact with the government, probing the ins-and-outs of government data is a different thing. What separates government online today compared with 10 years ago is that, in the past, governments typically provided online information: websites listing hours of operation or interfaces to databases that might have more detailed information. Today, many governments are trying to provide underlying data that it collects for public use — and touting it as a feature to the general public. The kinds of entrepreneurial activity new government data sources can spur range from home energy management to analytics for investment decisions.11

At the same time, many government data initiatives play out within government, with their impacts felt only through programmatic impacts. In Indiana, for example, the state Department of Child Services has fostered data sharing across different state bureaucracies to help case workers address child abuse problems more effectively. In Boston, improved data sharing within government helped the city’s 311 call system migrate to the Citizen’s Connect web-based system to address citizen complaints about garbage collection or traffic.12

In both entrepreneurial and service delivery examples, data are inputs that eventually connect to outcomes that consumers and citizens experience. However, as with many products, the inputs may be obscure to the average user. For these reasons, it is perhaps understandable that people are less attuned to them than more traditional online government applications. This shows up when exploring how effectively they think government shares the data it collects with the general public.

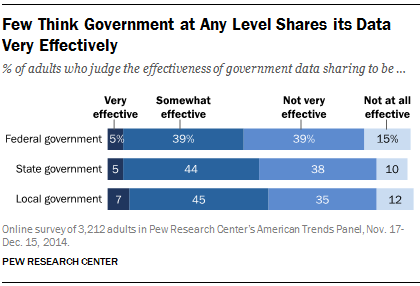

Few people think that governments — no matter what the level — are very effective at sharing data with the public. Just 11% of adults across all three levels of government think this about any level of government. Sizable numbers occupy the middle — three-quarters or somewhat more say governments do this somewhat or not very effectively. Still, 44% think the Federal government shares data at least somewhat effectively and roughly half say this about state and local governments.

Few people think that governments — no matter what the level — are very effective at sharing data with the public. Just 11% of adults across all three levels of government think this about any level of government. Sizable numbers occupy the middle — three-quarters or somewhat more say governments do this somewhat or not very effectively. Still, 44% think the Federal government shares data at least somewhat effectively and roughly half say this about state and local governments.

The main difference between those who think governments share data very effectively compared with those who do not think they share data effectively at all is party affiliation. Among those (11%) who think all levels of government share data effectively, 57% identify as Democrats (including those who lean Democratic) and 34% as Republicans (including those who lean Republican).

People’s tepid awareness of government data shows up when they are asked to state whether they could think of an example where government has done a good job providing information to the public about the data it collects and if they could think of an example where government does not provide enough useful data and information about the data it collects.

- 19% could think of an example where their local government did a good job providing information to the public about data it collects.

- 19% could recall an instance in which local government did not provide enough useful information.

This comes to a minority of respondents — 31% altogether — who could think of a positive or negative example of local government providing to the public information about its data collection activities.

Those who could give an example of how government did a good job or did a bad job sharing data were offered the chance, in an open-ended fashion, to describe it. These comments — a non-scientific dive into people’s perspectives— provide additional context on how people see government data. Among those that offered positive examples, comments suggest that they value the availability of government data on demography, crime, the economy, and government budgets. Many comments touch on basic information, with some noting they appreciate the ease of finding out about park hours, leaf collection, or the time and place of public meetings. Transparency, in other words, is a key value for many commenters on government data-sharing practices.

For those citing examples where government did a bad job sharing data, many communicated frustration with how governments presented data online. These respondents seemed to struggle at getting what they want online when they sought out data or information on a particular topic. Some respondents also criticized their local governments for not updating their websites about things such as road construction or development projects. Finally, some respondents expressed suspicions that their local government had a disposition against being transparent, meaning these respondents doubted that government data and information were complete or reliable.

Two additional things emerge from the comments of respondents who opted to share thoughts about how their local governments share data — both the good and the bad. First, these commenters seem to engage with government data as information-seekers, rather than as heavily engaged citizen-analysts. Second, many commenters express a desire to have more context and meaning be part of their interactions with government data. They value demographic or budget data, but would appreciate additional information (e.g., trends, understanding cost and benefits of projects) that might involve greater analysis of the data. This desire signals an opportunity for those interested in putting government data to better use for the public.

Another sign that Americans are not close followers of government data initiatives is evident when they are asked whether their local government has done more or less with respect to data sharing. Just 7% say government has provided more information about the data it collects in the past 12 months and 14% say it has provided less information. Large numbers either do not know (39%) or think government has provided about the same amount of information about the data it collects (also 39%).

The story is mixed for using government sources to find out about different topics. For topics that have cross-cutting resonance for many people, sizable minorities of Americans have used a government source to search for information:

- 38% have searched for climate, weather or pollution levels.

- 38% have searched for transportation issues, including road conditions and public transit.

- 36% have searched for crime reports in their area.

When it comes to more detailed searches that involve monitoring government performance, fewer users take advantage of government sources for these purposes:

When it comes to more detailed searches that involve monitoring government performance, fewer users take advantage of government sources for these purposes:

- 20% have used government sources to find information about student or teacher performance.

- 17% have used government sources to look for information on the performance of hospitals or healthcare providers.

- 7% have used government sources to find out about contracts between government agencies and outside firms.

Whether it is perceptions about government’s effectiveness in sharing data, recollections of local governments sharing data or use of government sources to monitor performance, only a minority have deep connections to data resources that really dig into government.

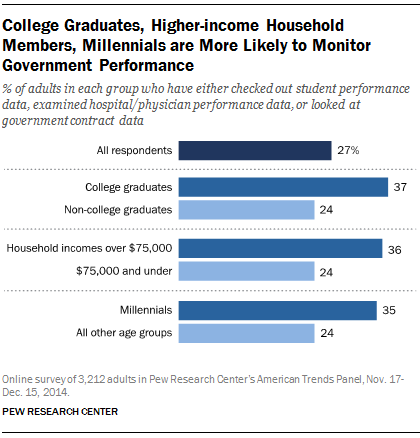

Overall, some 27% of Americans have done at least one of the three activities listed above that pertain to monitoring government performance. The main differences across demographic categories are education, income and age. Some 37% of college graduates have done one of the activities associated with monitoring government performance, as do 36% of those whose household incomes exceed $75,000 per year. Some 35% of millennials have done one of the three activities associated with monitoring government performance.

People often use government data, even if they do not recognize that — especially those who rely on weather and location apps

Although most people do not go too deeply into the inner workings of government data, the story is different when it comes to applications that rely on government data. The survey asked smartphone users in the sample — about two-thirds in all — whether they used specific apps on their smartphone. Here is what smartphone users say:

- 84% of smartphone owners use weather apps that let them know the weather forecast where they are.

- 81% use map apps that allow them to navigate through a city or neighborhood.

- 66% use apps that let them know about nearby restaurants, bars or stores.

- 31% use apps that inform them about public transportation, such as bus or train schedules.

- 14% use apps such as Uber or Lyft that allow them to hire nearby cars.

Nearly all smartphone owners (92%) have used at least one of these apps.

These apps are location-based services that build off of the Global Positioning System, while weather apps also rely on data from the U.S. government’s National Weather Service. For the most part, smartphone users are fine with letting their devices share their location with app providers. Some 56% share their location for at least some of their apps (38% do so for some of them, 18% for all of them).

Yet smartphone users have mixed views on the bargain that usually goes with downloading apps: share behavioral data with app providers in exchange for a free or cheap app. Specifically:

- 47% say this describes their views: Allowing apps to know their location is worth it because of the services they get. 51% say it does not describe their views.

- Just 20% agree with the idea that sharing their location with apps created from government data improves how government provides services. Fully 79% say it does not describe their views.

- 35% say this statement describes their views: “I usually read the ‘terms of service’ statements of location apps before I agree to allow my location data to be collected.” Some 63% says it does not describe their views.

The findings point to a familiar dynamic in how people approach many online consumer applications. They like the convenience of internet-enabled applications, use them when they need them, but express caution at having their use of data understood or monitored by others. And most do not often delve into the details.

Through their usage patterns, people clearly indicate that mobile apps have value to them, notwithstanding some hesitancy in sharing personal data that help make them run, particularly when it means sharing data with government. People are supportive of the notion that government sharing data with the public creates value for the economy, if not that wholeheartedly. Some 50% of all Americans say the data the government shares with the public helps businesses create new products and services at least somewhat. But only 9% think this helps “a lot” and 41% say it helps “somewhat.” The remainder either think the impact is minor (34% say government data helps the economy either not much or not at all, and 16% had no opinion). Smartphone users are only slightly more likely to say this — 53% say government data sharing helps businesses create new products and services.

When government data hits close to home, people have mixed views

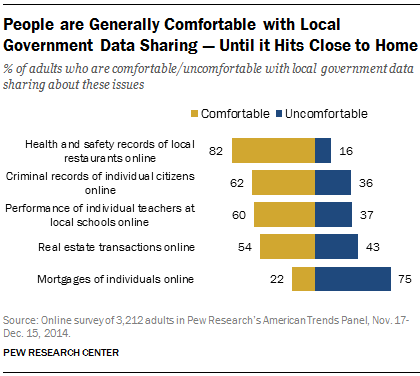

Another dimension of government data initiatives which the survey explored was people’s attitudes about applications involving government sharing data online. Some of those applications relate to information about individuals or their communities. People’s level of comfort with data sharing varied depending on the different uses of the data.

In general, people are fairly comfortable about the government putting online data on topics such as health and safety records of restaurants or criminal records. However, as the questions touch on things that are close to home, some worry arises. Three-quarters are uncomfortable about information about people’s mortgage being posted to the internet. About four- in-ten (43%) are uncomfortable about government providing online general information about real estate transactions.

When looking across all five topics, some 82% of adults are uncomfortable with at least one of the items listed and 66% are uncomfortable with two. This suggests that, even in light of solid levels of comfort with government providing specific information about individuals and communities online, there is a degree of concern in the general population about this practice — especially when it comes to people’s homes.

When looking across all five topics, some 82% of adults are uncomfortable with at least one of the items listed and 66% are uncomfortable with two. This suggests that, even in light of solid levels of comfort with government providing specific information about individuals and communities online, there is a degree of concern in the general population about this practice — especially when it comes to people’s homes.

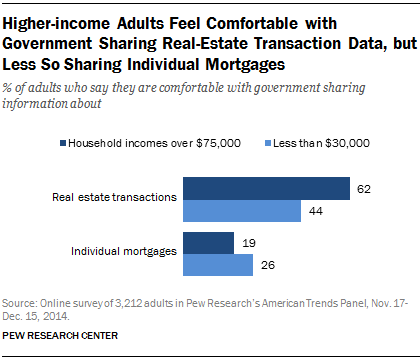

As to demographics, an interesting pattern emerges when looking at people’s levels of comfort about sharing real estate information generally versus sharing information on individual mortgages. When it comes to income, relatively well-off and lower income respondents present contrasts. More than half (62%) of those in homes with annual incomes over $75,000 per year are comfortable sharing information about real estate transactions online, while less than half (44%) of those in homes where annual incomes fall beneath $30,000 say this. For online sharing of individual mortgage information, just 19% of those in higher income homes are comfortable with this while a larger share (26%) of lower income respondents say this. The same pattern is true for education. Some 65% of college graduates feel comfortable sharing information about real estate transactions versus 44% of those with high school educations or less; 19% of college grads are fine sharing individual mortgage information online compared with 24% of less educated respondents.

People more likely to own homes (i.e., well-off respondents) are more skittish about sharing individual mortgage information online than those less likely to own homes. Those who are better off financially are more likely to be comfortable about having general information about real estate available online than lower-income homes, perhaps because such information is useful to well-off households who are more likely to be active in the real estate market.

People more likely to own homes (i.e., well-off respondents) are more skittish about sharing individual mortgage information online than those less likely to own homes. Those who are better off financially are more likely to be comfortable about having general information about real estate available online than lower-income homes, perhaps because such information is useful to well-off households who are more likely to be active in the real estate market.

There are also differences across racial and ethnic categories. Whites are somewhat more likely than African Americans and Hispanics to say they are comfortable having information about real estate shared online; 56% of whites are, compared with 51% of Hispanics and 49% of African Americans. However, African Americans and Hispanics are significantly more likely to be comfortable with having information about individual mortgages shared online. Specifically:

- 30% of African Americans are comfortable with individual mortgage information being shared online.

- 29% of Hispanics say this.

- 18% of white respondents say this.

The differences could be attributable, in part at least, to lower homeownership rates for African Americans and Hispanics. Some 42.1% of African Americans own their home and 44.5% of Hispanics do; this compares with the 72.3% figure for whites and 64.0% for all Americans.13