Twitter conversations have six different structures ranging from Polarized Crowds that focus on political issues to Community Clusters that gather to comment on global news stories

Media contacts

Lee Rainie – lrainie@pewresearch.org/pewresearch-org/internet and 202-419-4510 Marc A. Smith –marc@smrfoundation.org and (425) 241-9105

Washington (February 20, 2014) – People connect to form groups on Twitter for a variety of purposes. The networks they create have identifiable contours that are shaped by the topic being discussed, the information and influencers driving the conversation, and the social network structures of the participants.

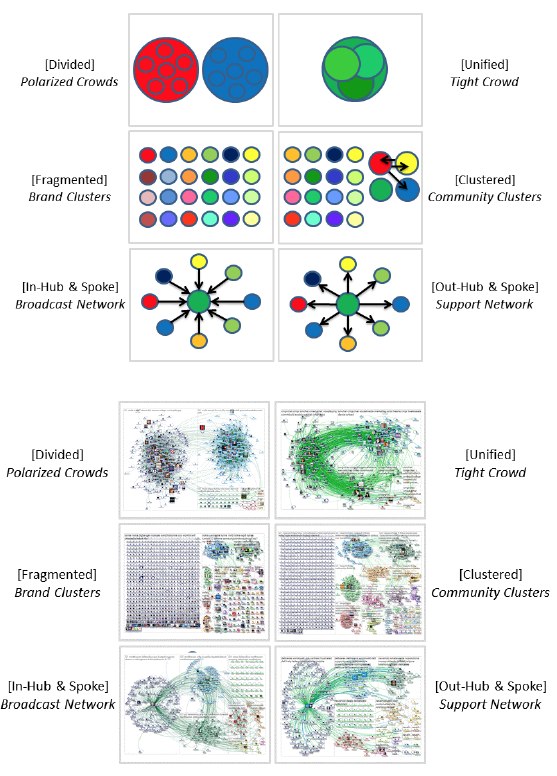

A special analysis by the Pew Research Center and the Social Media Research Foundation of thousands of Twitter conversations finds there are six distinct patterns to the conversational and social structures that take place on Twitter:

- Polarized Crowds often form around political topics: If the subject is political, it is common on Twitter to see two separate, polarized crowds take shape. The participants in one group mostly do not interact with people in the other group. Those in each cluster commonly mention very different collections of website URLs and use distinct hashtags and words in their tweets. Each group centers on different influential tweeters. Why this matters: It underscores that partisan Twitter users rely on different information sources and commonly do not interact with those on the other side on Twitter.

- Tight Crowds are shared spaces of learning and passion: Many conferences, professional topics, hobby groups, and other subjects that attract likeminded communities form the shape of a Tight Crowd. There are different clusters of conversations in these networks, but people are closely tied to each other, even to those in other groups. Why this matters: These structures show how networked learning communities function and how sharing and mutual support can be facilitated by social media.

- Brand Clusters are formed around products and celebrities: When well-known products or services or popular subjects like celebrities are discussed in Twitter, there are often many comments from participants who have no connections to one another. Well-known brands and other popular subjects can attract large fragmented Twitter populations who Tweet about it but not to each other. Why this matters: There are still institutions and topics that command mass interest but do not lead to the creation of connected conversations in a group.

- Community Clusters are created around global news: Some popular topics may develop multiple smaller groups, which often form around a few hubs each with its own audience, influencers, and sources of information. Conversations in these Community Clusters look like bazaars which host multiple centers of activity. Global news stories often attract coverage from many news outlets, each with its own following. Why this matters: Some information sources and subjects ignite multiple conversations, each cultivating its own audience and community. Community Clusters networks can reveal the diversity of opinion and perspective on a social media topic.

- Broadcast Network structures are created when people re-tweet breaking news and commentary from pundits: Twitter commentary around breaking news stories and the output of well-known media outlets and pundits has a distinctive hub and spoke structure in which many people repeat what prominent news and media organizations tweet. The members of the Broadcast Network audience are often connected only to the hub news source, without connecting to one another. Why this matters: Broadcast Network hubs are potent agenda setters and conversation starters in the new social media world. Enterprises and personalities with loyal followings can still have a large impact on the conversation.

- Support Network conversations revolve around a singular source: Customer complaints for a major business are often handled by a Twitter service account that attempts to resolve and manage customer issues around their products and services. This produces a hub and spoke structure that is different from the Broadcast Network pattern. In the Support Network structure, the hub account replies-to many otherwise disconnected users, creating an outward hub. In contrast, in the Broadcast pattern, the hub gets replied to or re-tweeted by many disconnected people, creating an inward hub. Why this matters: As government, businesses, and groups increasingly provide services and support via social media, the support network structures becomes an important benchmark for evaluating the performance of these institutions.

We can visualize the different structures using a schematic diagram and a real world example of that pattern in Twitter:

The analysis and these maps of social structures were created using an open-source tool called NodeXL that is a plug-in to Excel spreadsheets which allows researchers to examine the interplay of tweets, retweets, Twitter messages and the social networks of Twitter users – the people they follow and who follow them.

“Social media is increasingly home to civil society, the place where knowledge sharing, public discussions, debates, and disputes are carried out,” noted Marc A. Smith, the Director of the Social Media Research Foundation and a main author of a new report on Twitter maps. “These network maps provide new insights into the role social media play in society. Our work is in the spirit of observational researchers like 17th century botanists describing the variety of flowers on a newly discovered island or astronomers whose new telescopes that allow them to see different categories of galaxies. We are looking at things that have existed for a while, but with new tools that allow us to describe them in fresh ways.”

It is important to remember that the people who take the time to post and talk about any subject — political or otherwise – on Twitter are a special group. Their conversations are not representative of the views or behaviors of the full Twitterverse. Moreover, Twitter users are only 18% of internet users and 14% of the overall adult population. Still, the structure of these Twitter conversations says something meaningful about how engaged users discuss topics, find each other, and share information.

“These maps provide insights into people’s behavior in a way that complements and expands on traditional research methods such as public opinion surveys, focus groups, and even sentiment analysis of texts,” said Lee Rainie, Director of the Pew Research Center Internet Project. “It gives us a way to take the digital equivalent of aerial photos of crowds and simultaneously listen to their conversations.”

One of the main insights of this work is that each of the network structures has an opposite: They can be divided into pairs: divided Polarized Crowds in contrast to unified Tight Crowds; fragmented Brand Clusters in contrast to relatively cohesive Community Clusters; inward facing hubs and spoke Broadcast Networks in contrast to outward facing Support Networks.

“In polarized crowds, typically triggered by controversial political issues, users interact with like-minded users, receive their information from sources they agree with and link to websites that support their opinions,” noted Professor Itai Himelboim from the University of Georgia and a co-author of the report. “It reminds me of ‘high school politics’ – we don’t talk with you, we don’t listen to you, but we definitely talk about you.”

Among other things, social network mapping can identify and highlight key people in influential locations in a discussion network.

“These are data-driven early steps in understanding Twitter discussion structures that contribute to the emerging science of social participation,” said Prof. Ben Shneiderman of the University of Maryland, who is also a report co-author. “This new field is emerging right before our eyes and could eventually have a large impact on our understanding of everything from health to community safety, from business innovation to citizen science, and from civic engagement to sustainable energy programs.”