For one-third of U.S. adults, the internet is a diagnostic tool

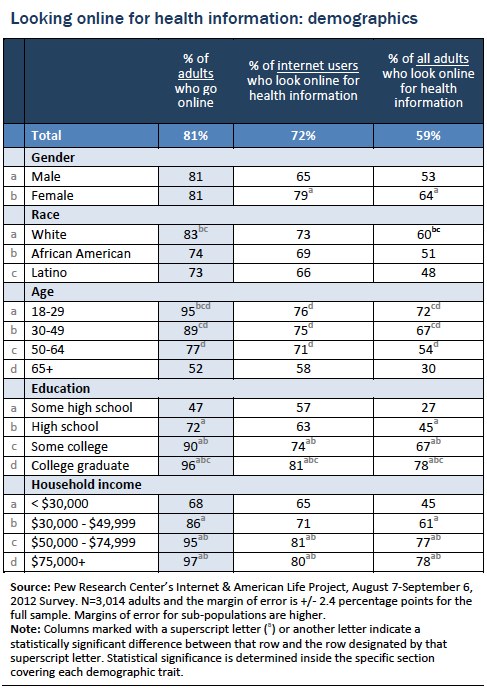

As of September 2012, 81% of U.S. adults use the internet and, of those, 72% say they have looked online for health information in the past year.

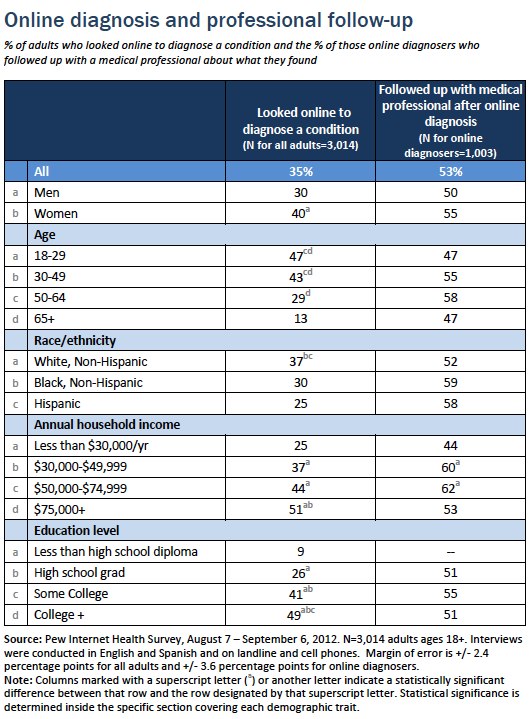

Since online personal diagnosis is a scenario that has intrigued observers for years – and caused some anxiety about people’s ability to navigate the online information landscape – the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project explored it in some depth in its most recent health survey. Of those who have looked online for health information, 59% say they have ever gone online specifically to try to figure out what medical condition they or someone else might have. That translates to 35% of U.S. adults.

Women are more likely than men to go online to figure out a possible diagnosis. Other groups that have a high likelihood of doing so include younger people, white adults, those in the highest income bracket, and those with more education (see table below for details).

The following analysis is based on questions asked only of that 35% of the population who answered that they have gone online to figure out what they or someone else might have. We will refer to them as “online diagnosers.”

First, online diagnosers were asked if the information they found online led them to think that this was a condition that needed the attention of a doctor or other medical professional, or that it was perhaps something they could take care of at home:

- 46% of online diagnosers say that the condition needed the attention of a doctor;

- 38% say it could be taken care of at home; and

- 11% said it was either both or in-between.

Fifty-three percent of online diagnosers say they talked with a medical professional about what they found online, 46% did not (see table below for details).

Separately, we asked if a medical professional confirmed what they thought the condition was and found that:

- 41% of online diagnosers say yes, a medical professional confirmed their suspicions. An additional 2% say a medical professional partially confirmed them.

- 35% say they did not visit a clinician to get a professional opinion.

- 18% say a medical professional either did not agree or offered a different opinion about the condition.

- 1% say their conversation with a clinician was inconclusive – the professional was unable to diagnose what they had.

There is no statistically significant difference between those who have health insurance and those who do not when it comes to using the internet to figure out an illness.

It is important to note what these findings mean – and what they don’t mean. Historically, people have always tried to answer their health questions at home and made personal choices about whether and when to consult a clinician. Many have now added the internet to their personal health toolbox, helping themselves and their loved ones better understand what might be ailing them. This study was not designed to determine whether the internet has had a good or bad influence on health care. It measures the scope, but not the outcome, of this activity.

Eight in ten online health inquiries start at a search engine

Again, 72% of internet users say they looked online for health information within the past year. For brevity’s sake, we will refer to this group as “online health seekers.”

When asked to think about the last time they did so, 77% of online health seekers say they began at a search engine such as Google, Bing, or Yahoo. Another 13% say they began at a site that specializes in health information, like WebMD. Just 2% say they started their research at a more general site like Wikipedia and an additional 1% say they started at a social network site like Facebook.

Using a search engine is somewhat associated with being younger. For example, 82% of online health seekers age 18-29 years old say they used Google, Bing, Yahoo, or another search engine, compared with 73% of those ages 50 and older.

Overall, this pattern matches what we found in our very first health survey, conducted in 2000, when just half of U.S. adults had internet access. Then, as now, eight in ten online health seekers started at a general search engine when looking online for health or medical information.

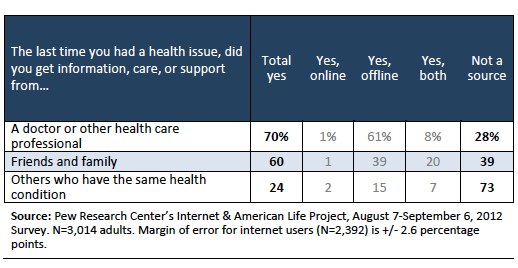

Clinicians are a central resource for information or support

To try to capture an accurate picture of people’s health information seeking strategies, we asked respondents to think about the last time they had a serious health issue and to whom they turned for help:

- 70% of U.S. adults got information, care, or support from a doctor or other health care professional.

- 60% of adults got information or support from friends and family.

- 24% of adults got information or support from others who have the same health condition.

The vast majority of this care and conversation took place offline (see table below).

Certain groups are significantly more likely to report calling upon a clinician for health advice: women, adults ages 50 and older, non-Hispanic whites, and adults with at least some college education. Fully three-quarters of people who have health insurance consulted a doctor or other health care professional, compared with half (49%) of the uninsured.

Women are more inclined than men to seek information, care, or support from friends and family: 68% vs. 53%. Non-Hispanic whites, adults with health insurance, and those with some college education are also more likely than other groups to turn to friends and family. Almost two-thirds (63%) of those with insurance approached friends and family, while half (48%) of the uninsured did so.

Differences among demographic groups are less apparent when looking at peer health support, but two groups stand out: women and people with health insurance. Twenty-eight percent of women have sought advice from others who have the same health condition, compared with 21% of men. One-quarter (26%) of the insured sought out others with the same health condition, compared to 19% of those without insurance.

These findings reflect differences we first observed in 2010, with little change over the past two years.

Half of online health inquiries are on behalf of someone else

When asked to think about the last time they went online for health or medical information, 39% of internet users who have done this type of research say they looked for information related to their own situation. Another 39% say they looked for information related to someone else’s health or medical situation. And 15% of these internet users say they were looking both on their own and someone else’s behalf.

Online health seekers age 65 and older are more likely than those in the middle age groups to say their last search was on their own behalf: 48%, compared with 39% of 50-64 year-olds, for example. Parents are more likely than non-parents to look on behalf of someone else: 44%, compared with 36%.

This trend has not changed significantly since we first began tracking it in 2000: more than half of health searches are conducted on behalf of someone not touching the keyboard.

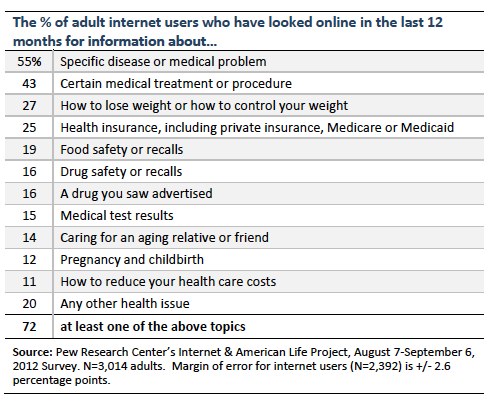

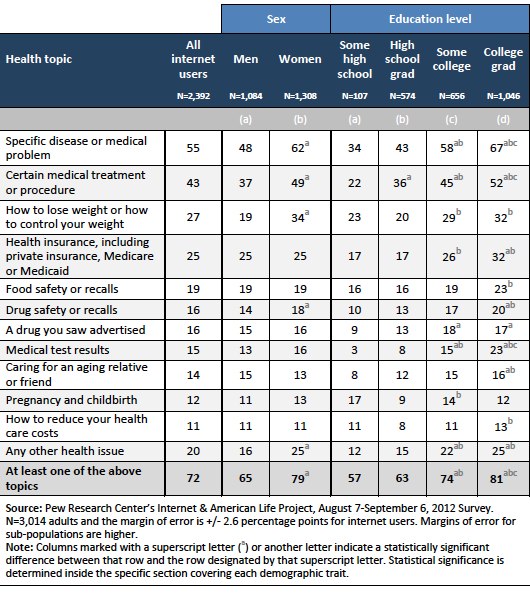

Specific diseases and treatments continue to dominate people’s online queries

In past surveys, the Pew Internet Project has not defined a time period for health searches online. This time, the phrase “in the past 12 months” was added to help focus respondents on recent searches.

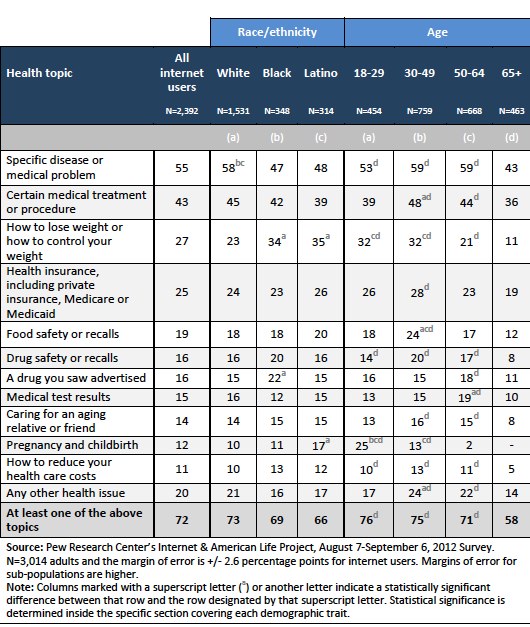

As one would expect, the percentages dipped for each of the topics we include in the list. For example, 55% of internet users say they looked online for information about a specific disease or medical problem in the past year, compared with 66% of internet users who, in 2010, said they had ever done such a search.

Women are more likely than men to seek health information online, as are internet users with higher levels of education:

There are only four significant differences among white, African American, and Latino internet users when it comes to health topics: specific diseases, weight control, a drug seen in advertising, and pregnancy. Differences among age groups are a much more mixed bag of topics.

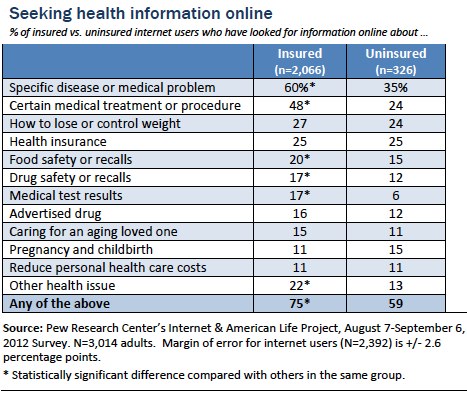

Internet users with health insurance are significantly more likely than those without health insurance to research certain topics, such as a specific disease or treatment. Other topics, such as food and drug safety, are moderately more popular among internet users with health insurance, compared with those who do not report having insurance coverage.

Internet access drives information access

Since one in five U.S. adults do not go online, the percentage of online health information seekers is lower when calculated as a percentage of the total population: 59% of all adults in the U.S. say they looked online for health information within the past year.

There are two forces at play: access to the internet and interest in health information. For example, women and men are equally likely to have access to the internet, but women are more likely than men to report gathering health information online, which explains the gender gap in the chart below. For the other groups, their overall lower rate of internet adoption combined with lower levels of health information seeking online drives their numbers down significantly when compared with other adults.

Younger adults and minorities lead the way with mobile health information search

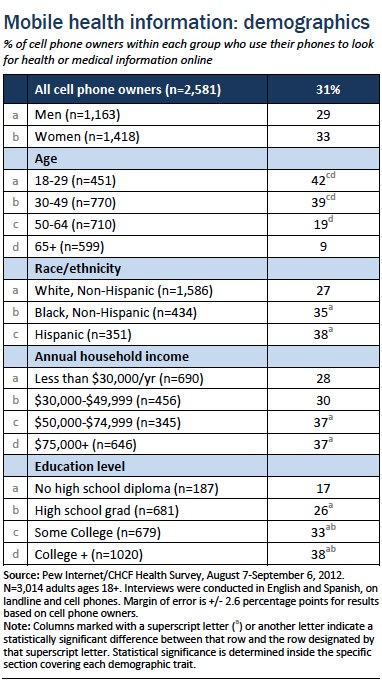

Some 85% of U.S. adults own a cell phone and, of those, 31% say they have used their phone to look for health or medical information online. Some groups are more likely than others to look for health information on their phones: Latinos, African Americans, those between the ages of 18 and 49, and those who have attended at least some college education.

Half of smartphone owners have used their phone to look up health information

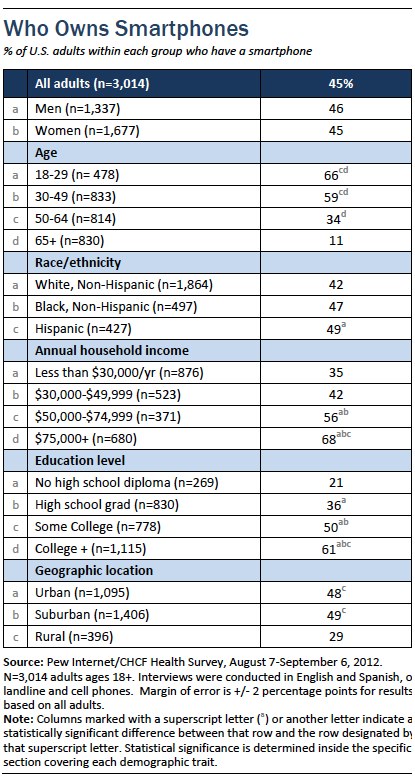

Half of cell phone owners in the U.S. (53%) say that they own a smartphone. This translates to 45% of all American adults. Younger people are more likely than older adults to own a smartphone, as are people with higher income and education levels.

Fifty-two percent of smartphone owners have looked up health information on their phone, compared with just 6% of other cell phone owners.

A person’s likelihood to use his or her cell phone to look for health information is amplified by each of the characteristics identified in the tables above: relative youthfulness, having a higher level of education, living in a higher-income household, being Latino, being African American – and owning a smartphone. Each of these observations holds true under statistical analysis isolating each factor. In other words, it is not just that smartphone owners are likely to be younger than other American adults and both groups are likely to use their phones to look up health information. Each characteristic has an independent effect on mobile health information consumption.

One in four people seeking health information online have hit a pay wall

Twenty-six percent of internet users who look online for health information say they have been asked to pay for access to something they wanted to see online. Seventy-three percent say they have not faced this choice while seeking health or medical information online.

Of those who have been asked to pay, just 2% say they did so. Fully 83% of those who hit a pay wall say they tried to find the same information somewhere else. Thirteen percent of those who hit a pay wall say they just gave up.

Men, women, people of all ages and education levels were equally likely to report hitting a pay wall when looking for health information. Respondents living in lower-income households were significantly more likely than their wealthier counterparts to say they gave up at that point. Wealthier respondents were the likeliest group to say they tried to find the same information elsewhere. No income group was more likely to say they paid the fee.