Overview

Three-quarters of AP and NWP teachers say that the internet and digital search tools have had a “mostly positive” impact on their students’ research habits, but 87% say these technologies are creating an “easily distracted generation with short attention spans” and 64% say today’s digital technologies “do more to distract students than to help them academically.”

These complex and at times contradictory judgments emerge from 1) an online survey of more than 2,000 middle and high school teachers drawn from the Advanced Placement (AP) and National Writing Project (NWP) communities; and 2) a series of online and offline focus groups with middle and high school teachers and some of their students. The study was designed to explore teachers’ views of the ways today’s digital environment is shaping the research and writing habits of middle and high school students. Building on the Pew Internet Project’s prior work about how people use the internet and, especially, the information-saturated digital lives of teens, this research looks at teachers’ experiences and observations about how the rise of digital material affects the research skills of today’s students.

Overall, teachers who participated in this study characterize the impact of today’s digital environment on their students’ research habits and skills as mostly positive, yet multi-faceted and not without drawbacks. Among the more positive impacts they see: the best students access a greater depth and breadth of information on topics that interest them; students can take advantage of the availability of educational material in engaging multimedia formats; and many become more self-reliant researchers.

At the same time, these teachers juxtapose these benefits against some emerging concerns. Specifically, some teachers worry about students’ overdependence on search engines; the difficulty many students have judging the quality of online information; the general level of literacy of today’s students; increasing distractions pulling at students and poor time management skills; students’ potentially diminished critical thinking capacity; and the ease with which today’s students can borrow from the work of others.

These teachers report that students rely mainly on search engines to conduct research, in lieu of other resources such as online databases, the news sites of respected news organizations, printed books, or reference librarians.

Overall, the vast majority of these teachers say a top priority in today’s classrooms should be teaching students how to “judge the quality of online information.” As a result, a significant portion of the teachers surveyed here report spending class time discussing with students how search engines work, how to assess the reliability of the information they find online, and how to improve their search skills. They also spend time constructing assignments that point students toward the best online resources and encourage the use of sources other than search engines.

These are among the main findings of an online survey of a non-probability sample of 2,462 middle and high school teachers currently teaching in the U.S., Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, conducted between March 7 and April 23, 2012. Some 1,750 of the teachers are drawn from a sample of advanced placement (AP) high school teachers, while the remaining 712 are from a sample of National Writing Project teachers. Survey findings are complemented by insights from a series of online and in-person focus groups with middle and high school teachers and students in grades 9-12, conducted between November, 2011 and February, 2012.

This particular sample is quite diverse geographically, by subject matter taught, and by school size and community characteristics. But it skews towards “cutting edge” educators who teach some of the most academically successful students in the country. Thus, the findings reported here reflect the realities of their special place in American education, and are not necessarily representative of all teachers in all schools. At the same time, these findings are especially powerful given that these teachers’ observations and judgments emerge from some of the nation’s most advanced classrooms.

The internet and digital technologies are significantly impacting how students conduct research: 77% of these teachers say the overall impact is “mostly positive,” but they sound many cautionary notes

Asked to assess the overall impact of the internet and digital technologies on students’ research habits, 77% of these teachers say it has been “mostly positive.” Yet, when asked if they agree or disagree with specific assertions about how the internet is impacting students’ research, their views are decidedly mixed.

On the more encouraging side, virtually all (99%) AP and NWP teachers in this study agree with the notion that the internet enables students to access a wider range of resources than would otherwise be available, and 65% also agree that the internet makes today’s students more self-sufficient researchers.

At the same time, 76% of teachers surveyed “strongly agree” with the assertion that internet search engines have conditioned students to expect to be able to find information quickly and easily. Large majorities also agree with the assertion that the amount of information available online today is overwhelming to most students (83%) and that today’s digital technologies discourage students from using a wide range of sources when conducting research (71%). Fewer teachers, but still a majority of this sample (60%), agree with the assertion that today’s technologies make it harder for students to find credible sources of information.

The internet has changed the very meaning of “research”

Perhaps the greatest impact this group of teachers sees today’s digital environment having on student research habits is the degree to which it has changed the very nature of “research” and what it means to “do research.” Teachers and students alike report that for today’s students, “research” means “Googling.” As a result, some teachers report that for their students “doing research” has shifted from a relatively slow process of intellectual curiosity and discovery to a fast-paced, short-term exercise aimed at locating just enough information to complete an assignment.

These perceptions are evident in teachers’ survey responses: 94% of the teachers surveyed say their students are “very likely” to use Google or other online search engines in a typical research assignment, placing it well ahead of all other sources that we asked about. Second and third on the list of frequently used sources are online encyclopedias such as Wikipedia, and social media sites such as YouTube. In descending order, the sources teachers in our survey say students are “very likely” to use in a typical research assignment:

- Google or other online search engine (94%)

- Wikipedia or other online encyclopedia (75%)

- YouTube or other social media sites (52%)

- Their peers (42%)

- Spark Notes, Cliff Notes, or other study guides (41%)

- News sites of major news organizations (25%)

- Print or electronic textbooks (18%)

- Online databases such as EBSCO, JSTOR, or Grolier (17%)

- A research librarian at their school or public library (16%)

- Printed books other than textbooks (12%)

- Student-oriented search engines such as Sweet Search (10%)

In response to this trend, many teachers say they shape research assignments to address what they feel can be their students’ overdependence on search engines and online encyclopedias. Nine in ten (90%) direct their students to specific online resources they feel are most appropriate for a particular assignment, and 83% develop research questions or assignments that require students to use a wider variety of sources, both online and offline.

Most teachers encourage online research, including the use of digital technologies such as cell phones to find information quickly, yet point to barriers in the school environment impeding quality online research

Asked which online activities they have students engage in, 95% of the teachers in this survey report having students “do research or search for information online,” making it the most common online task. Conducting research online is followed by accessing or downloading assignments (79%) or submitting assignments (75%) via online platforms.

These teachers report using a wide variety of digital tools in their classrooms and assignments, well beyond the typical desktop and laptop computers. Specifically, majorities say they and/or their students use cell phones (72%), digital cameras (66%), and digital video recorders (55%) either in the classroom or to complete school assignments. Cell phones are becoming particularly popular learning tools, and are now as common to these teachers’ classrooms as computer carts. According to respondents, the most popular school task students use cell phones for is “to look up information in class,” cited by 42% of the teachers participating in the survey.

Yet, survey results also indicate teachers face a variety of challenges in incorporating digital tools into their classrooms, some of which, they suggest, may hinder how students are taught to conduct research online. Virtually all teachers surveyed work in a school that employs internet filters (97%), formal policies about cell phone use (97%) and acceptable use policies or AUPs (97%). The degree to which teachers feel these policies impact their teaching varies, with internet filters cited most often as having a “major impact” on survey participants’ teaching (32%). One in five teachers (21%) say cell phone policies have a “major” impact on their teaching, and 16% say the same about their school’s AUP. These impacts are felt most strongly among those teaching the lowest income students.

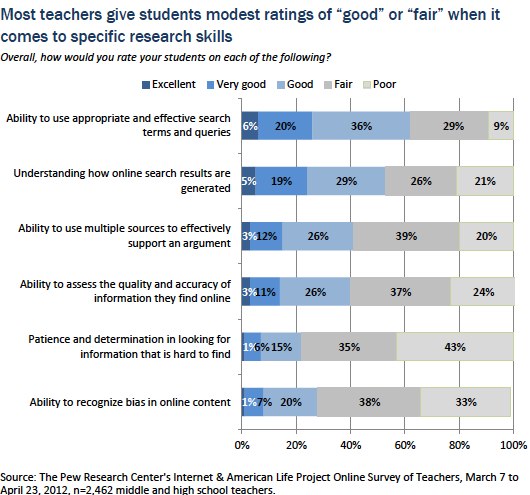

Teachers give students’ research skills modest ratings

Despite viewing the overall impact of today’s digital environment on students’ research habits as “mostly positive,” teachers rate the actual research skills of their students as “good” or “fair” in most cases. Very few teachers rate their students “excellent” on any of the research skills included in the survey. This is notable, given that the majority of the sample teaches Advanced Placement courses to the most academically advanced students.

Students receive the highest marks from these teachers for their ability to use appropriate and effective search queries and their understanding of how online search results are generated. Yet even for these skills, only about one-quarter of teachers surveyed here rate their students “excellent” or “very good.” Indeed, in our focus groups, many teachers suggest that despite being raised in the “digital age,” today’s students are surprisingly lacking in their online search skills. Students receive the lowest marks for “patience and determination in looking for information that is hard to find,” with 43% of teachers rating their students “poor” in this regard, and another 35% rating their students “fair.”

Given these perceived deficits in key skills, it is not surprising that 80% of teachers surveyed say they spend class time discussing with students how to assess the reliability of online information, and 71% spend class time discussing how to conduct research online in general. Another 57% spend class time helping students improve their search skills and 35% devote class time to helping students understand how search engines work and how search results are generated. In addition, asked what curriculum changes might be necessary in middle and high schools today, 47% “strongly agree” and 44% “somewhat agree” that courses or content focusing on digital literacy must be incorporated into every school’s curriculum.

A richer information environment, but at the price of distracted students?

Teachers are evenly divided on the question of whether today’s students are fundamentally different from previous generations; 47% agree and 52% disagree with the statement that “today’s students are really no different than previous generations, they just have different tools through which to express themselves.” Responses to this item were consistent across the full sample of teachers regardless of the teachers’ age or experience level, the subject or grade level taught, or the type of community in which they teach.

At the same time, asked whether they agree or disagree that “today’s students have fundamentally different cognitive skills because of the digital technologies they have grown up with,” 88% of the sample agree, including 40% who “strongly agree.” Teachers of the lowest income students are the most likely to “strongly agree” with this statement (46%) but the differences across student socioeconomic status are slight, and there are no other notable differences across subgroups of teachers in the sample.

Overwhelming majorities of these teachers also agree with the assertions that “today’s digital technologies are creating an easily distracted generation with short attention spans” (87%) and “today’s students are too ‘plugged in’ and need more time away from their digital technologies” (86%). Two-thirds (64%) agree with the notion that “today’s digital technologies do more to distract students than to help them academically.” In focus groups, some teachers commented on the connection they see between students’ “overexposure” to technology, and the resulting lack of focus and diminished ability to retain knowledge they see among some students. Time management is also becoming a serious issue among students, according to some teachers; in their experience, today’s digital technologies not only encourage students to assume all tasks can be finished quickly and at the last minute, but students also use various digital tools at their disposal to “waste time” and procrastinate.

Thus, despite 77% of the survey respondents describing the overall impact of the internet and digital technologies on students’ research habits as “mostly positive,” the broad story is more complex. While majorities of teachers surveyed see the internet and other digital technologies encouraging broader and deeper learning by connecting students to more resources about topics that interest them, enabling them to access multimedia content, and broadening their worldviews, these teachers are at the same time concerned about digital distractions and students’ abilities to focus on tasks and manage their time. While some frame these issues as stemming directly from digital technologies and the particular students they teach, others suggest the concerns actually reflect a slow response from parents and educators to shape their own expectations and students’ learning environments in a way that better reflects the world today’s students live in.

About the data collection

Data collection was conducted in two phases. In phase one, Pew Internet conducted two online and one in-person focus group with middle and high school teachers; focus group participants included Advanced Placement (AP) teachers, teachers who had participated in the National Writing Project’s Summer Institute (NWP), as well as teachers at a College Board school in the Northeast U.S. Two in-person focus groups were also conducted with students in grades 9-12 from the same College Board school. The goal of these discussions was to hear teachers and students talk about, in their own words, the different ways they feel digital technologies such as the internet, search engines, social media, and cell phones are shaping students’ research and writing habits and skills. Teachers were asked to speak in depth about teaching research and writing to middle and high school students today, the challenges they encounter, and how they incorporate digital technologies into their classrooms and assignments.

Focus group discussions were instrumental in developing a 30-minute online survey, which was administered in phase two of the research to a national sample of middle and high school teachers. The survey results reported here are based on a non-probability sample of 2,462 middle and high school teachers currently teaching in the U.S., Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Of these 2,462 teachers, 2,067 completed the entire survey; all percentages reported are based on those answering each question. The sample is not a probability sample of all teachers because it was not practical to assemble a sampling frame of this population. Instead, two large lists of teachers were assembled: one included 42,879 AP teachers who had agreed to allow the College Board to contact them (about one-third of all AP teachers), while the other was a list of 5,869 teachers who participated in the National Writing Project’s Summer Institute during 2007-2011 and who were not already part of the AP sample. A stratified random sample of 16,721 AP teachers was drawn from the AP teacher list, based on subject taught, state, and grade level, while all members of the NWP list were included in the final sample.

The online survey was conducted from March 7–April 23, 2012. More details on how the survey and focus groups were conducted are included in the Methodology section at the end of this report, along with focus group discussion guides and the survey instrument.

About the teachers who participated in the survey

There are several important ways the teachers who participated in the survey are unique, which should be considered when interpreting the results reported here. First, 95% of the teachers who participated in the survey teach in public schools, thus the findings reported here reflect that environment almost exclusively. In addition, almost one-third of the sample (NWP Summer Institute teachers) has received extensive training in how to effectively teach writing in today’s digital environment. The National Writing Project’s mission is to provide professional development, resources and support to teachers to improve the teaching of writing in today’s schools. The NWP teachers included here are what the organization terms “teacher-consultants” who have attended the Summer Institute and provide local leadership to other teachers. Research has shown significant gains in the writing performance of students who are taught by these teachers.1

Moreover, the majority of teachers participating in the survey (56%) currently teach AP, honors, and/or accelerated courses, thus the population of middle and high school students they work with skews heavily toward the highest achievers. These teachers and their students may have resources and support available to them—particularly in terms of specialized training and access to digital tools—that are not available in all educational settings. Thus, the population of teachers participating in this research might best be considered “leading edge teachers” who are actively involved with the College Board and/or the National Writing Project and are therefore beneficiaries of resources and training not common to all teachers. It is likely that teachers in this study are developing some of the more innovative pedagogical approaches to teaching research and writing in today’s digital environment, and are incorporating classroom technology in ways that are not typical of the entire population of middle and high school teachers in the U.S. Survey findings represent the attitudes and behaviors of this particular group of teachers only, and are not representative of the entire population of U.S. middle and high school teachers.

Every effort was made to administer the survey to as broad a group of educators as possible from the sample files being used. As a group, the 2,462 teachers participating in the survey comprise a wide range of subject areas, experience levels, geographic regions, school type and socioeconomic level, and community type (detailed sample characteristics are available in the Methodology section of this report). The sample includes teachers from all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. All teachers who participated in the survey teach in physical schools and classrooms, as opposed to teaching online or virtual courses.

English/language arts teachers make up a significant portion of the sample (36%), reflecting the intentional design of the study, but history, social science, math, science, foreign language, art, and music teachers are also represented. About one in ten teachers participating in the survey are middle school teachers, while 91% currently teach grades 9-12. There is wide distribution across school size and students’ socioeconomic status, though half of the teachers participating in the survey report teaching in a small city or suburb. There is also a wide distribution in the age and experience levels of participating teachers. The survey sample is 71% female.

About the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project

The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project is one of seven projects that make up the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan, nonprofit “fact tank” that provides information on the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. The Project produces reports exploring the impact of the internet on families, communities, work and home, daily life, education, health care, and civic and political life. The Pew Internet Project takes no positions on policy issues related to the internet or other communications technologies. It does not endorse technologies, industry sectors, companies, nonprofit organizations, or individuals. While we thank our research partners for their helpful guidance, the Pew Internet Project had full control over the design, implementation, analysis and writing of this survey and report.

About the College Board

The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of over 6,000 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org.

About the National Writing Project

The National Writing Project (NWP) is a nationwide network of educators working together to improve the teaching of writing in the nation’s schools and in other settings. NWP provides high-quality professional development programs to teachers in a variety of disciplines and at all levels, from early childhood through university. Through its nearly 200 university-based sites serving all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, NWP develops the leadership, programs and research needed for teachers to help students become successful writers and learners. For more information, visit www.nwp.org.