Overview of responses

In a survey about the future impact of the internet, a solid majority of technology experts and stakeholders said the Millennial generation will lead society into a new world of personal disclosure and information-sharing using new media. These experts said the communications patterns “digital natives” have already embraced through their use of social networking technology and other social technology tools will carry forward even as Millennials age, form families, and move up the economic ladder.

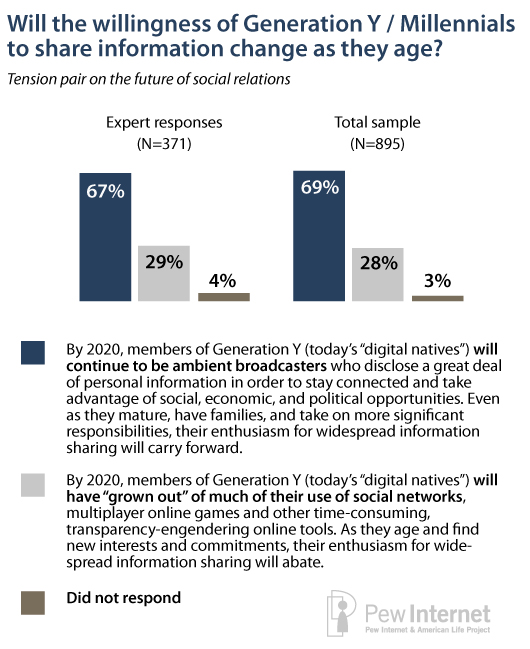

The highly engaged, diverse set of respondents to an online, opt-in survey included 895 technology stakeholders and critics. The study was fielded by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center.

Some 67% agreed with the statement:

- “By 2020, members of Generation Y (today’s “digital natives”) will continue to be ambient broadcasters who disclose a great deal of personal information in order to stay connected and take advantage of social, economic, and political opportunities. Even as they mature, have families, and take on more significant responsibilities, their enthusiasm for widespread information sharing will carry forward.”

Some 29% agreed with the opposite statement, which posited:

- “By 2020, members of Generation Y (today’s “digital natives”) will have “grown out” of much of their use of social networks, multiplayer online games and other time-consuming, transparency-engendering online tools. As they age and find new interests and commitments, their enthusiasm for widespread information sharing will abate.”

Most of those surveyed noted that the disclosure of personal information online carries many social benefits as people open up to others in order to build friendships, form and find communities, seek help, and build their reputations. They said Millennials have already seen the benefits and will not reduce their use of these social tools over the next decade as they take on more responsibilities while growing older.

The majority argued in answers to the survey that new social norms that reward disclosure are already in place among the young The experts also expressed hope that society will be more forgiving of those whose youthful mistakes are on display in social media such as Facebook picture albums or YouTube videos.

Some said new definitions of “private” and “public” information are taking shape in networked society. They argued that this means that Millennials might change the kinds of personal information they share as they age, but the aging process will not fundamentally change the incentives to share.

At the same time, some experts said an awkward trial-and-error period is unfolding and will continue over the next decade, as people adjust to new realities about how social networks perform and as new boundaries are set about the personal information that is appropriate to share.

Nearly 30 percent of respondents disagreed with the majority, most of them noting that life stages and milestones do matter and do prompt changes in behavior. They cited an array of factors that they believe will compel Millennials to pull back on their free-wheeling lifecasting, including: fears that openness about their personal lives might damage their professional lives, greater seriousness in dating and family formation as people age, and the arrival of children in their lives.

Among other things, many of the dissenting experts also said Millennials will not have as much time in the future to devote to popular activities such as frequently posting to the world at large on YouTube, Twitter or Facebook about the nitty-gritty of their lives.

Also in this report:

» The future of Millennials: Main findings and respondents’ thoughts

‘Tension pairs’ were designed to provoke detailed elaborations

This material was gathered in the fourth “Future of the Internet” survey conducted by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center. The surveys are conducted through online questionnaires to which a selected group of experts and the highly engaged Internet public have been invited to respond. The surveys present potential-future scenarios to which respondents react with their expectations based on current knowledge and attitudes. You can view detailed results from the 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010 surveys here: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/topics/Future-of-the-Internet.aspx and http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/default.xhtml. Expanded results are also published in the “Future of the Internet” book series published by Cambria Press.

The surveys are conducted to help accurately identify current attitudes about the potential future for networked communications and are not meant to imply any type of futures forecast.

Respondents to the Future of the Internet IV survey, fielded from Dec. 2, 2009 to Jan. 11, 2010, were asked to consider the future of the Internet-connected world between now and 2020 and the likely innovation that will occur. They were asked to assess 10 different “tension pairs” – each pair offering two different 2020 scenarios with the same overall theme and opposite outcomes – and they were asked to select the one most likely choice of two statements. The tension pairs and their alternative outcomes were constructed to reflect previous statements about the likely evolution of the Internet. They were reviewed and edited by the Pew Internet Advisory Board. Results have been released in six reports over the course of 2010. The results in this sixth and final report are responses to a tension pair that relates to the future use of social technology applications by Generation Y, also known as the Millennials. About the other reports:

- REPORT 1: Results to five tension pairs relating to the Internet and the evolution of intelligence, reading and the rendering of knowledge, identity and authentication, gadgets and applications, and the core values of the Internet were released earlier in 2010 at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/Future-of-the-Internet-IV.aspx.

- REPORT 2: Results from a tension pair on the impact of the internet on institutions were discussed at the Capital Cabal in Washington, DC, on March 31, 2010: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/Impact-of-the-Internet-on-Institutions-in-the-Future.aspx.

- REPORT 3: Results from a tension pair assessing people’s opinions on the future of the semantic web were announced at the WWW2010 and FutureWeb conferences in Raleigh, NC, April 28, 2010: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/Semantic-Web.aspx

- REPORTS 4 and 5: Other results were released here: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/The-future-of-social-relations.aspx and https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/The-future-of-cloud-computing.aspx.

A presentation summarizing the full Future of the Internet IV findings are being released July 9 at the 2010 World Future Society conference (http://www.wfs.org/meetings.htm).

About the survey and the participants

Please note that this survey is primarily aimed at eliciting focused observations on the likely impact and influence of the Internet – not on the respondents’ choices from the pairs of predictive statements. Many times when respondents “voted” for one scenario over another, they responded in their elaboration that both outcomes are likely to a degree or that an outcome not offered would be their true choice. Survey participants were informed that “it is likely you will struggle with most or all of the choices and some may be impossible to decide; we hope that will inspire you to write responses that will explain your answer and illuminate important issues.”

Experts were located in two ways. First, several thousand were identified in an extensive canvassing of scholarly, government, and business documents from the period 1990-1995 to see who had ventured predictions about the future impact of the Internet. Several hundred of them participated in the first three surveys conducted by Pew Internet and Elon University, and they were recontacted for this survey. Second, expert participants were selected due to their positions as stakeholders in the development of the Internet.

Here are some of the respondents: Clay Shirky, Esther Dyson, Doc Searls, Nicholas Carr, Susan Crawford, David Clark, Jamais Cascio, Peter Norvig, Craig Newmark, Hal Varian, Howard Rheingold, Andreas Kluth, Jeff Jarvis, Andy Oram, Kevin Werbach, David Sifry, Dan Gillmor, Marc Rotenberg, Stowe Boyd, Andrew Nachison, Anthony Townsend, Ethan Zuckerman, Tom Wolzien, Stephen Downes, Rebecca MacKinnon, Jim Warren, Sandra Brahman, Barry Wellman, Seth Finkelstein, Jerry Berman, Tiffany Shlain, and Stewart Baker.

The respondents’ remarks reflect their personal positions on the issues and are not the positions of their employers, however their leadership roles in key organizations help identify them as experts. Following is a representative list of some of the institutions at which respondents work or have affiliations: Google, Microsoft. Cisco Systems, Yahoo!, Intel, IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Ericsson Research, Nokia, New York Times, O’Reilly Media, Thomson Reuters, Wired magazine, The Economist magazine, NBC, RAND Corporation, Verizon Communications, Linden Lab, Institute for the Future, British Telecom, Qwest Communications, Raytheon, Adobe, Meetup, Craigslist, Ask.com, Intuit, MITRE Corporation, Department of Defense, Department of State, Federal Communications Commission, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Social Security Administration, General Services Administration, British OfCom, World Wide Web Consortium, National Geographic Society, Benton Foundation, Linux Foundation, Association of Internet Researchers, Internet2, Internet Society, Institute for the Future, Santa Fe Institute, Yankee Group

Harvard University, MIT, Yale University, Georgetown University, Oxford Internet Institute, Princeton University, Carnegie-Mellon University, University of Pennsylvania, University of California-Berkeley, Columbia University, University of Southern California, Cornell University, University of North Carolina, Purdue University, Duke University , Syracuse University, New York University, Northwestern University, Ohio University, Georgia Institute of Technology, Florida State University, University of Kentucky, University of Texas, University of Maryland, University of Kansas, University of Illinois, Boston College.

While many respondents are at the pinnacle of Internet leadership, some of the survey respondents are “working in the trenches” of building the web. Most of the people in this latter segment of responders came to the survey by invitation because they are on the email list of the Pew Internet & American Life Project or are otherwise known to the Project. They are not necessarily opinion leaders for their industries or well-known futurists, but it is striking how much their views were distributed in ways that paralleled those who are celebrated in the technology field.

While a wide range of opinion from experts, organizations, and interested institutions was sought, this survey should not be taken as a representative canvassing of Internet experts. By design, this survey was an “opt in,” self-selecting effort. That process does not yield a random, representative sample. The quantitative results are based on a non-random online sample of 895 Internet experts and other Internet users, recruited by email invitation, Twitter, or Facebook. Since the data are based on a non-random sample, a margin of error cannot be computed, and results are not projectable to any population other than the respondents in this sample.

Many of the respondents are Internet veterans – 50% have been using the Internet since 1992 or earlier, with 11% actively involved online since 1982 or earlier. When asked for their primary area of Internet interest, 15% of the survey participants identified themselves as research scientists; 14% as business leaders or entrepreneurs; 12% as consultants or futurists, 12% as authors, editors or journalists; 9% as technology developers or administrators; 7% as advocates or activist users; 3% as pioneers or originators; 2% as legislators, politicians or lawyers; and 25% specified their primary area of interest as “other.”

The answers these respondents gave to the questions are given in two columns. The first column covers the answers of 371 longtime experts who have regularly participated in these surveys. The second column covers the answers of all the respondents, including the 524 who were recruited by other experts or by their association with the Pew Internet Project. Interestingly, there is not great variance between the smaller and bigger pools of respondents.