Parents’ and teens’ overall assessment of the role of cell phones in their lives

Parents and teens have quite similar overall attitudes about the role of cell phones in their lives, though teens are more likely to salute the upside of constant connectivity and bemoan the downside. Perpetual availability breeds safety – or at least safer feelings — and the capacity to reach others anywhere, any time has some social payoffs. Moreover, the cell phone itself can be a “companion” for many teens when they are bored and want to entertain themselves. Still, there are new realities with which teens must come to terms in the age of mobile communication. What balance should I strike in being available and being more private? What volume of chatter fits my social life and my needs? How much of my time should I allow to be interrupted by others? This survey tried to get at some of these questions by asking parent and teen respondents about their attitudes towards statements about the possibilities and problems associated with cell phones.

Safety first – females are particularly pleased and parents say it’s a major reason for owning a cell phone.

For many cell phone owners, safety is a primary benefit. Fully 98% of parents agree with the statement: “A major reason my child has a cell phone is so we can be in touch no matter where he/she is.” Every African-American parent in our survey whose teenage child has a cell phone agreed with this assertion, as did 98% of white parents and 95% of Hispanic parents.

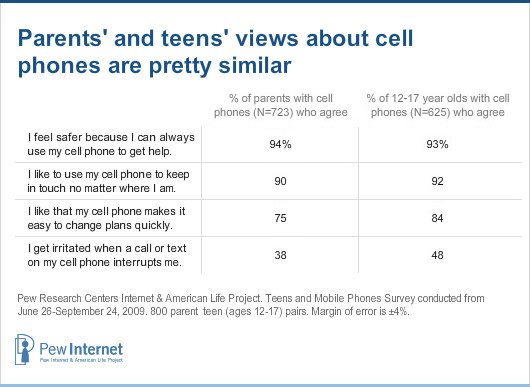

Moreover, personal safety is a significant factor among those who own cell phones. Fully 94% of parents and 93% of those ages 12-17 agreed with the statement: “I feel safer because I can always use my cell phone to get help.” Girls and mothers are more likely than boys and fathers to agree with that. Some 97% of teen girls ages 12-to-17 who own cell phones and 98% of the mothers who own cell phones agree with the statement that they feel safer “because I can always use my cell phone to get help.” That compares with 89% of teen boys and 89% of fathers who say they agree with that statement. Every single girl respondent in our survey who was age 12 or 13 said she agreed with this statement and 95% of the older teen girls – those ages 14-17 – agreed.

In contrast to the near-universal appeal of the safety dimensions of cell ownership, this study wanted to see if parents felt that maintaining their child’s friendships was a primary motivation for acquiring this new communication tool. Just 36% of parents with a teenager who has a cell phone agreed with the statement: “A major reason my child has a cell phone is to keep in touch with friends.” Fathers (44%) were more likely than mothers (31%) to agree that a major reason their children had cell phones was to keep in touch with friends. Parents of older teens were more likely to agree with this than parents of younger teens.

Focus group discussions with teens bore out these findings. Asked when and why they first got a cell phone, most teens cited the safety, security and ease of communication with parents provided by cell phones as the initial reason they got one. Many said that getting a cell phone was their parents’ idea, not their own. Typical is the story of one high school boy, who explained that he got his cell phone “when I was twelve…my mom got it for me to communicate with my parents, if I was going to be late from school or walking home. I didn’t care that much about it. It was cool to have, but I got along fine without it.” Other teens expressed similar sentiments; one high school girl said, “My parents were more of the instigators and actually got it for me, rather than me asking for it,” while a middle school boy explained, “I was ten, but I didn’t really need it. But my parents thought it was time I get one.”

It was clear from the focus groups that at least in the beginning, parents rely more on the cell phone for its connectivity than do their children, and that safety is usually driving the decision to purchase a child his or her first cell phone. Over time, as the teen masters the phone and incorporates it into his or her social life, the balance shifts and the phone becomes a core communication tool for the child.

Still, teens—especially teen girls—appreciate the security a cell phone provides and come to rely on it. One high school girl described herself as being “hysterical” for several hours when she found herself home alone without her cell phone, fearing that something would happen to her and she would not be able to call someone for help. This may be an extreme example, but it speaks to the sense of security a cell phone provides, for both teens and their parents.

Always connected – a liberating advantage when it comes to parental contact.

Some 92% of 12-17 year-olds who own cell phones and 90% of teens’ parents backed the assertion that they like cell phones because they can “keep in touch no matter where I am.” Again, this benefit was particularly appealing to girls (97%) and mothers (92%) compared with boys and fathers. Other Pew Internet research has shown that females are more likely than males to use – and appreciate – a host of communications tools and the cell phone is no exception.

The survey asked a further question of the younger respondents and found that teen girls who owned cell phones were more likely than boys to agree with the statement: “My cell phone gives me more freedom because I can stay in touch with my parents no matter where I am.” Fully 94% of all teen cell owners agreed with this and the gender breakdown was notable – 97% of girls backed the statement vs. 92% of the boys. The oldest girls, those ages 14-17, were the most likely of all to see cell phones as technologies of freedom. Girls who texted were even more likely to salute the liberating aspects of cell ownership than those who are not texters.

[a cell phone]

Yet, despite the clear upside of connectivity with parents, some teens in the focus groups acknowledged that constant connectivity with parents can be a double-edged proposition. Several teens said that carrying a cell phone meant they “had no excuses” for not telling their parents where they were, and that it provided their parents an easy way to monitor and check up on their teens. As one high school boy put it, his mother uses the cell phone to “just to see where we at, to be in our business.” Asked the worst thing about cell phones, one high school girl said emphatically, “That my parents can contact me at any hour of the day!”

[My parents]

Changing plans on the fly – a major boon.

One of the major changes that mobile phones have introduced to the social world is that they allow people to coordinate their schedules and meeting places and then micro-coordinate a rendezvous. The cell phone gives teens (and others) the ability to call directly to one another and iteratively work out the time and the location of their meeting. Having a cell phone means that they are not stuck sitting at home waiting for the phone to ring as they plan their social lives. Rather, they can be en route to a location and, if better alternatives arise, they can adjust their plans as needed. This individual addressability gives them flexibility in their planning that was not there for earlier generations. Youth ages 12-17 who own cell phones are even more appreciative of this feature of mobile connectivity than their parents are. While 75% of parents appreciate the flexibility the phone gives them, some 84% of cell-owning teens in our survey agreed with the assertion: “I like that my cell phone makes it easy to change plans quickly.” High school-age teens are the most supportive of this feature of mobile life: 87% of the 14-17 year-olds agreed with the statement.

Teens in our focus groups repeatedly cited this benefit of cell phones, a high school boy going so far as to say, “If you didn’t have texting or AIM, I wouldn’t know how to make plans.” Others noted that when planning a get together with many people, texting allows them to communicate plans to the entire group all at once, whereas phoning each person individually or even doing group calls is cumbersome and time-consuming. It is clear that as the number of people to be included increases, this iterative planning becomes more difficult. However, for smaller groups of individuals, planning and coordinating via the cell phone is a boon.

In general, focus group participants extolled these social benefits of cell phones, and described them as central to their social planning and activity. Many felt that without cell phones, their social lives would be quite different. A typical comment from one younger high school boy:

- I think if you have a cell phone, it adds to you being able to, like, actually hang out with people because you can find out, ‘Oh, where you at, I’ll come meet you’ or, ‘I’ll come over to your house’ or, ‘You come over to my house,’ or ‘Do you want to meet you and go to this movie’ or whatever. But if you’re just, if you don’t have a cell phone and you’re out doing stuff, and someone is trying to contact you wanting to hang out, then you have to wait until you go home and check your email or something, because they can’t reach you if you’re out.

Several boys in the same group said that at times, when they had lost their phones, they socialized much less with their friends because it was too difficult to contact them to make plans. As one younger high school boy described it, the week his phone was broken “was the boringest week of my life. The first day without my phone, like, I didn’t text anybody. I felt like, ‘Where did all my friends go?’ like I moved or something, because no one knew my house number. So I just sat there, and it was during summer break too!” Another high school-age boy said that when he was without his phone, he stayed home rather than go to the trouble of walking to his friend’s house to see if he was home.

Not only did teens extol the virtues of phones for making social plans with friends, they also cited many examples of ways that their cell phones allow them to coordinate the activities of social groups to which they belong, such as school clubs and sports teams. It was not uncommon, teens told us, for coaches, captains, counselors and fellow teens to text important messages to the group, such as whether activities were canceled, where meetings would take place, and the like.

Interestingly, the teens in the focus groups recognized a trade-off in this element of cell phones as well. As one high school girl expressed it, while cell phones allow teens to change plans on the fly, that also means “plans can be more tentative because you can change them on a moment’s notice. So that can be bad or good.” It seems at least some teens are concerned that mobile connectivity might result in people being less committed to plans once set.

[emphasis added]

The prospect of constant interruptions – an annoyance to boys and younger teens.

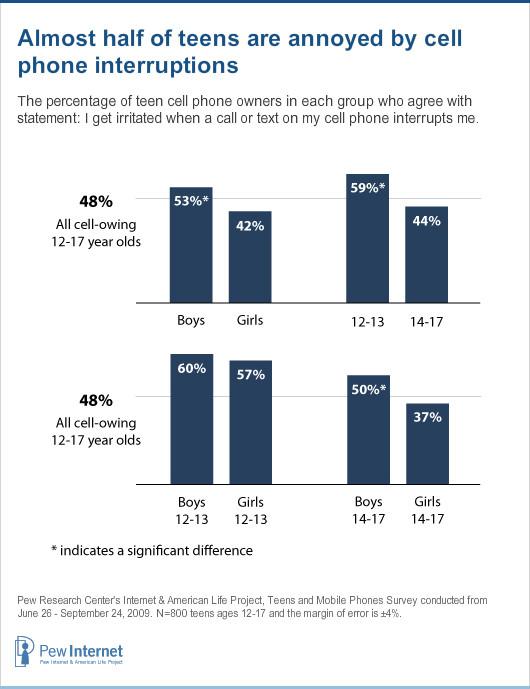

While many cell owners appreciate that they can initiate contact with others whenever the urge strikes them, a portion of cell owners see an annoying element to constant connectivity: the likelihood of interruptions. As much as they like their mobile phones, teen owners are more likely than parent owners to agree with the statement: “I get irritated when a call or text on my cell phone interrupts me.” Nearly half of 12-17 year-old cell owners (48%) agree with that statement compared with 38% of parents. Teen boys and younger owners of either gender are likely to back this notion: 53% of cell-owning boys and 59% of all cell owners ages 12 and 13 agree that cell-initiated interruptions are irritating. Older girls ages 14-17 are calmer about interruptions. Only 37% of cell-owning older girls say cell calls or text interruptions can be annoying. Overall, teens send and receive more text messages than parents, which may contribute to their greater sense of irritation – the typical teen sends or receives 50 text messages a day, while the average adult 18 and older has sent and received 10 messages in the last 24 hours.

Another possible explanation for these differences is that younger teens may be learning how to incorporate cell phones into the social rhythms of their lives and finding it harder at the earlier stages of ownership to balance the new demands for accessibility and “interrupt-ability” that mobile phones bring.

The gender differences can also explain some of the fact that teen boys generally do not use their cell phones as avidly as girls. So, boys might not be as willing to accept the fact that interruptions are part of the lifestyle that goes with perpetual connectivity. The focus groups illustrated many of these gender differences in how boys and girls perceive and use the phone. Boys in the group consistently described texting with their friends as task-driven, and used phrases like “taking care of business” and “more to the point” to described the succinct nature with which they communicate with friends. In contrast, they described texting with girls as being more about flirting and getting to know one another. Typical of their comments are the following:

- [Texting with girls] is just like b.s., like you don’t really need to be talking to them but you just are because you like them, they like you. With your other [male] friends, it’s just like ‘Oh, we’re going to go to the movies and then do this and do that.’ And that’s it. (Boy, high school)

- If I text my friend, it’s not for conversation. It’s like ‘Hey, I’m headed home from school, where are you?’ And then ‘Oh, I’m over here at the store or something, I’ll be over in a minute.’ And that’s it. But when I’m talking with my girlfriend, it’s all day. So all day conversation. (Boy, middle school)

From these comments, it was apparent that the boys we spoke with were accustomed to using their phones as very direct, succinct communication tools to make plans and check in with one another, and would likely be less tolerant of more trivial contact.

Teens in the focus groups also addressed the issue of unwanted interruptions, and expressed annoyance at friends and acquaintances who violate cell phone etiquette. In the words of one high school boy,

- At least me personally, I’m the type of person where if I want to talk to you then I’ll talk to you. But people call me like all the time, like all types of times at night and in the mornings. It’s just like I don’t want to be bothered! Then, like, they text me and they get mad if I don’t text back, like, five seconds later. It just becomes a problem.

In particular, teens expressed annoyance with other teens who “don’t get the hint” when they do not return a text message or who insist on trying to reach them at times when they know the teen is unavailable (for example, during doctor’s appointments, class time, at night, etc.). As one girl related,

- I hate like, especially when it’s just me and my boyfriend hanging out, and my friends will just text me over and over, ‘what r u doing?, what r u doing?’ and they’ll resend it because they think you didn’t get it when really you’re just busy, and that’s when I’ll turn [my phone] off.

This was one of many stories teens related of friends texting the same message repeatedly, over the course of just a few minutes, in an attempt to get a response, or of texting question marks or “r u there?” messages if they do not get a response quickly enough. Teens are also annoyed when they do try to respond to a message immediately, and before they have a chance to hit send, the other person has already sent them another text.

To further probe the potential hassles of having cell phones, the survey asked teens to respond to the following item: “It is a lot of trouble to keep my cell phone with me all the time.” Just 26% of cell-owning 12-17 year-olds agreed with that statement. Again, boys and younger users were the most likely to agree: 32% of boys backed the assertion vs. 21% of girls; 33% of those ages 12 and 13 agreed vs. 23% of those ages 14-17. The largest cohort of those who said it was trouble to keep their phone with them all the time were 12- and 13 year-old boys: 42% of them agreed with the statement.

Connectivity can beat back boredom for two-thirds of teen cell owners.

In the survey, we asked teens about using their phones as a source of entertainment. Some 69% of teen cell owners agreed with the statement: “When I am bored, I use my cell phone to entertain myself.” This is especially true of girls. Some 77% of them say cell phones are good boredom killers, compared with 61% of boys.

Those who have more expensive and expansive cell phone plans are the most likely to say they use their cell phones to stave off boredom. Some 76% of teens who have unlimited text plans agree they use their phones to entertain themselves when they are bored. Furthermore, those who agree with this statement are likely to have used their cell phones in multiple ways and to use those data features often – not just for making calls. For instance:

- 83% of those who have used their cell phones to buy things agree that they use their phones for entertainment when they are bored.

- 72% of those who take pictures with their cell phones and 91% of those who use their cells several times a day to take pictures agree that they use their phones to entertain themselves when they are bored.

- 84% of those who send emails on their cell phones and 89% of those who send emails several times a day say they use their phones to entertain themselves when they are bored.

- 72% of text message users and 79% of those who send text messages several times a day say they use their phones to entertain themselves when they are bored.

- 79% of those who play music on their cell phones and 85% of those who play music on their cell phones several times a day say they use their phones to entertain themselves when they are bored.

Teens in the focus groups confirmed these findings, citing all of these activities as ways they use their phones for entertainment. Those who did not engage in these activities typically said it was because their phone did not have that particular feature or it was too expensive (i.e. to download a game to their phone). Not surprisingly, many focus group participants expressed a desire for high-end phones with the latest features, such as iPhones and phones with touch screens. One entertainment function teens seemed to use quite often is taking pictures with their phones. As mentioned earlier in this report, several focus group respondents, mostly girls, said that they often take pictures of silly or interesting things they come across, just for fun or to share with friends.

Speaking to the extent to which teens rely on their phones for entertainment, several of the teens in the focus groups said they would not know how to occupy their time if they did not have their phones. In the words of one high school boy, when asked what it is like to not have your phone,

- It really sucks…you grow accustomed to having it so much, so like when you don’t have it you’ve got to find other things to occupy your time. I’ll be like, ‘I should read a book! No I shouldn’t, I should have my phone!’ And it just really sucks. But actually, like if you really think about how much you use your phone and how much more you could be doing with your time, if you look at it like that, then you are really wasting a lot of time.

Apart from the social and safety functions of cell phones, teens clearly utilize them as a tool for personal enjoyment, made easier with the increasingly advanced features of today’s cell phones.

Going off the grid – the coping strategy that works for half of teen cell owners.

For some teens, the mobile phone isn’t something that must remain on and connected at all time. Half of those ages 12-17 who own cells (50%) agree with the statement: “I occasionally turn off my cell phone when I do not have to do so.” Teens who have prepaid plans are more likely than those on family or individual cell plans to say they shut off the phone from time to time. Some 61% of those on prepaid plans shut the phone off occasionally vs. 48% of those on family plans and 47% of those on a separate plan. The analysis shows that 66% of those who pay for each text message are more likely to shut the phone off occasionally than those who buy a set number of text messages or have unlimited plans.

Younger users – those ages 12 and 13 – are notably more likely than older teens to say they voluntarily shut down their cell from time to time: 59% agreed with the statement vs. 47% of those ages 14-17. Boys in that younger cohort were the most likely to go off the grid from time to time: 61% reported shutting down their phones. Non-texters were more likely than texters (62% vs. 49%) to shut off their cell phones from time to time.

Focus groups revealed that teens are generally reluctant to shut their phones off completely, with many of the teens we spoke with saying adamantly that they never turn their phones off or turn them off only when the battery is dying or when they are getting spammed. When they want a “break” from their phones or are in a social setting where a noisy phone might be inappropriate or disrespectful, most teens prefer putting their phones on vibrate rather than turning them off completely. As one middle school boy explained, “If I’m sitting and watching TV I’ll have it on vibrate because like. . . or the sports game thing. . . my dad will normally be watching it with me or my mom and it gets really annoying if every time you get a text it goes ‘do-da-do-da-doo-doo.’”

Teens who do turn their phones off occasionally do so for a variety of reasons. Some do so when they want to concentrate on a task at hand, such as driving, taking a test, playing sports, or playing a video game. Others said they turn their phones off when on vacation, on holidays, when at church, or when at the dinner table. Still others said they turn their phones off when in a bad mood, when feeling uncommunicative, or when they are trying to avoid someone.

[my parents]

A small number of teens in the focus groups acknowledged that they welcome a break from their phones. As one high school girl explained, “I go to camp every year and we’re not supposed to bring our phones and I don’t like bringing my phone . . . It’s nice having a two-week break and you’re just like focused on camp and all the people there and stuff.” But statements like these were the exception. Teens in the focus groups more commonly described themselves as feeling “lost,” “naked” or “exposed” when they are without their phones. In the words of one high school girl,

- I know I never consider myself a person who is constantly on the phone, but then when I lost it for a couple of days I felt…I felt really exposed. I felt like I was missing a lot. Because I feel like it becomes almost like a security blanket, you know you can contact anybody if you have to. You can talk to a friend if you have to and even if you don’t, just the idea that you have it there in case you need it. I feel most people feel really uncomfortable when you don’t have it. Like, what if my mom was in an accident, what if she’s not going to pick me up, what do I do then? I don’t know what to do, and so even though I’m not constantly on it, without it, it is a little unnerving.

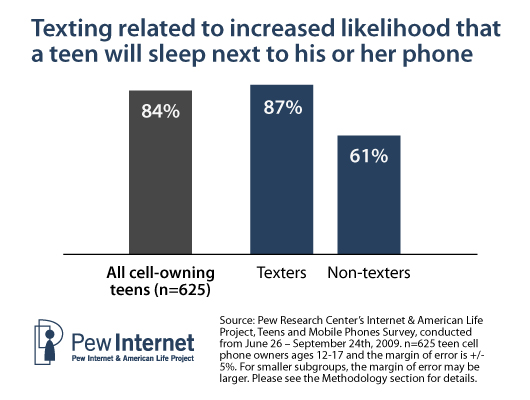

More than 4 in 5 teens with cell phones sleep with the phone on or near the bed.

To explore the how teens manage the deep connection some have with their cell phones, the survey asked whether they had ever slept with their phones on or with it right next to their beds. More than eight in ten cell-owning teens (84%) said yes, they had done this at some point. One motivation for having the phone nearby when sleeping is eventual connectivity. It is also worth noting that many teens use the clock function on their phone as an alarm clock. These middle school boys noted:

- Boy 1: I don’t turn it off at night, I always want to be able to check the time because I can’t really look at the clock without my glasses so I just look at the time.

- Boy 2: This is my clock. This is my watch.

- Boy 3: This is my alarm.

While the functionality of the clock might legitimize having the cell phone bedside, it is also a potential communication channel.

Older teens are more likely to sleep with their phones than younger teens. While 78% of cell-owning 12 and 13 year-olds have slept with their phones right next to them, that figure is 86% among cell-owning teens age 14 and older. Moreover, African-American teens and those from households with incomes below $50,000 are slightly more likely to engage in this behavior than other teen cell phone users. Among African-American cell-owning teens, 91% say they have slept with their phone on or right next to their bed, and among lower income cell-owning teens, 89% say they have done this.

But the biggest driver of whether a teen sleeps with their phone is texting. Teens who use their cell phones to text are 42% more likely to sleep with their phones than cell-owning teens that do not text.

The focus groups provided some insights into how and why teens stay connected to their phones at night. A fairly common practice seems to be sleeping with one’s phone under the pillow, so that it will wake the teen if someone is trying to contact them. Others say they fall asleep with the phone in their hand, sometimes mid-conversation, or keep the phone in bed with them or right beside them on their nightstand. Those who keep the phone under the pillow or in the bed say it is for practical reasons—they are concerned that the phone will fall off of their nightstands during the night and break, so they feel safer keeping it in bed with them.

Most teens in the focus groups said they do not like being called during the night unless it is an emergency, and they leave their phones on with the assumption that if they do get a call, it will be about something important. For this reason, most of the teens we spoke with said they are reluctant to turn their phones off altogether at night and turn it to vibrate instead so they can be contacted if necessary.

A small minority of teens we spoke with said they turn their phones off while sleeping, or set limits with friends for when it is, and is not, okay to contact them at night. As one girl explained, her voicemail recording tells friends that it is okay to contact her up until 10:30 PM, but no later. And another boy explained that his mother has set his phone to deactivate at 11:00 PM on school nights, and that he often has to tell his friends, much to their surprise, that he must end a conversation because he is going to bed.

Despite these measures, teens lament intrusive and frivolous calls and texts received at all hours of the night. Often, they are the pranks of bored friends or mischievous siblings. Other times, they are friends reaching out to chat. At those times, some teens feel obligated to respond. As one high school girl explained, “Our friends are texting constantly, and the people will wake me up at like midnight and I have to like wake up and talk to them or like they’ll think I’m mad at them or something.”

Feeling obligated to stay connected

The social expectations that are created by constant connectivity are not lost on teens, and are evident in some of the excerpts above. In addition, during the focus groups, teens related many stories of friends and acquaintances who get insulted, angry or upset if a text message or phone call is not responded to immediately. As a result, many teens we heard from said they feel obligated to return texts and calls as quickly as possible, to avoid such tensions and misunderstandings.

Several teens spoke to the perceived obligation that accompanies cell phones to always be reachable. One high school girl explained her frustration at these expectations:

- That is one aggravating thing I find about phones…when it gets to the point where you can receive like all your messages and all this, then you have no way of disconnecting. That didn’t used to bother me until on a family vacation, my uncle, the entire time typing his emails, doing his business. It’s like, ‘Why is it so hard for you to put that away for one day and enjoy like a family meal?’ And see because like everybody knows that this person can be contacted 24/7, that’s what they do, and then that person feels obligated…. A person gets to the point where they can’t, where you can’t just be like, ‘I’m going on a trip people, I’ll be gone for a week!’

At the end of several of the focus groups, participants were asked to share with the group what they thought were the best and worst things about having a cell phone. Several responded to this question by noting the tension between the benefits of always being connected with those around them and the downside of always being expected to be available. As one boy put it, “The best thing is that it’s so convenient and you can just talk to people all the time, and like even if you’re not at home, and like, the worst thing is like, when people keep calling you…it just gets annoying.” A high school girl echoed his sentiments when she said, “It just keeps you connected and you can talk to other people, but in return it also sometimes just gets annoying. People calling you…so kind of a give and take.”

Such feelings, while common, were not universal. There were a very small number of teens in the focus groups who seemed unconcerned with the social expectations that accompanied cell phone ownership or who managed others’ expectations by simply limiting their availability. As one boy explained, he is simply “bad at answering my cell phone, and um, I just leave it on the counter and walk somewhere else and come back and see missed call. So people expect that from me. They don’t expect necessarily a quick answer.”