The future of intelligence

Eminent tech scholar and analyst Nicholas Carr wrote a provocative cover story for the Atlantic Monthly magazine in the summer of 20081 with the cover line: “Is Google Making us Stupid?” He argued that the ease of online searching and distractions of browsing through the web were possibly limiting his capacity to concentrate. “I’m not thinking the way I used to,” he wrote, in part because he is becoming a skimming, browsing reader, rather than a deep and engaged reader. “The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas…. If we lose those quiet spaces, or fill them up with ‘content,’ we will sacrifice something important not only in our selves but in our culture.”

Jamais Cascio, an affiliate at the Institute for the Future and senior fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, challenged Carr in a subsequent article in the Atlantic Monthly (http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200907/intelligence). Cascio made the case that the array of problems facing humanity — the end of the fossil-fuel era, the fragility of the global food web, growing population density, and the spread of pandemics, among others – will force us to get smarter if we are to survive. “Most people don’t realize that this process is already under way,” he wrote. “In fact, it’s happening all around us, across the full spectrum of how we understand intelligence. It’s visible in the hive mind of the Internet, in the powerful tools for simulation and visualization that are jump-starting new scientific disciplines, and in the development of drugs that some people (myself included) have discovered let them study harder, focus better, and stay awake longer with full clarity.” He argued that while the proliferation of technology and media can challenge humans’ capacity to concentrate there were signs that we are developing “fluid intelligence—the ability to find meaning in confusion and solve new problems, independent of acquired knowledge.” He also expressed hope that techies will develop tools to help people find and assess information smartly.

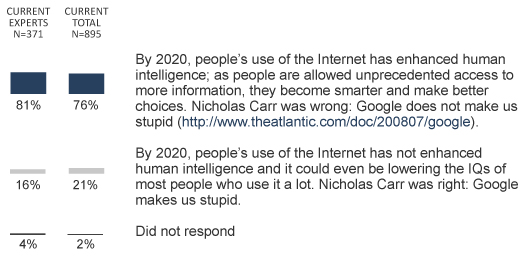

With that as backdrop, respondents were asked to explain their answer to the tension pair statements and “share your view of the Internet’s influence on the future of human intelligence in 2020 – what is likely to stay the same and what will be different in the way human intellect evolves?” What follows is a selection of the hundreds of written elaborations and some of the recurring themes in those answers:

Nicholas Carr and Google staffers have their say

“I feel compelled to agree with myself. But I would add that the Net’s effect on our intellectual lives will not be measured simply by average IQ scores. What the Net does is shift the emphasis of our intelligence, away from what might be called a meditative or contemplative intelligence and more toward what might be called a utilitarian intelligence. The price of zipping among lots of bits of information is a loss of depth in our thinking.”– Nicholas Carr

[the institution of time-management and worker-activity standards in industrial settings]

“Google will make us more informed. The smartest person in the world could well be behind a plow in China or India. Providing universal access to information will allow such people to realize their full potential, providing benefits to the entire world.” – Hal Varian, Google, chief economist

The resources of the internet and search engines will shift cognitive capacities. We won’t have to remember as much, but we’ll have to think harder and have better critical thinking and analytical skills. Less time devoted to memorization gives people more time to master those new skills.

“Google allows us to be more creative in approaching problems and more integrative in our thinking. We spend less time trying to recall and more time generating solutions.” – Paul Jones, ibiblio, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

“Google will make us stupid and intelligent at the same time. In the future, we will live in a transparent 3D mobile media cloud that surrounds us everywhere. In this cloud, we will use intelligent machines, to whom we delegate both simple and complex tasks. Therefore, we will loose the skills we needed in the old days (e.g., reading paper maps while driving a car). But we will gain the skill to make better choices (e.g., knowing to choose the mortgage that is best for you instead of best for the bank). All in all, I think the gains outweigh the losses.” — Marcel Bullinga, Dutch Futurist at futurecheck.com

“I think that certain tasks will be “offloaded” to Google or other Internet services rather than performed in the mind, especially remembering minor details. But really, that a role that paper has taken over many centuries: did Gutenberg make us stupid? On the other hand, the Internet is likely to be front-and-centre in any developments related to improvements in neuroscience and human cognition research.” – Dean Bubley, wireless industry consultant

“What the internet (here subsumed tongue-in-cheek under “Google”) does is to support SOME parts of human intelligence, such as analysis, by REPLACING other parts such as memory. Thus, people will be more intelligent about, say, the logistics of moving around a geography because “Google” will remember the facts and relationships of various locations on their behalf. People will be better able to compare the revolutions of 1848 and 1789 because “Google” will remind them of all the details as needed. This is the continuation ad infinitum of the process launched by abacuses and calculators: we have become more “stupid” by losing our arithmetic skills but more intelligent at evaluating numbers.” – Andreas Kluth, writer, Economist magazine

“It’s a mistake to treat intelligence as an undifferentiated whole. No doubt we will become worse at doing some things (‘more stupid’) requiring rote memory of information that is now available though Google. But with this capacity freed, we may (and probably will) be capable of more advanced integration and evaluation of information (‘more intelligent’).” – Stephen Downes, National Research Council, Canada

“The new learning system, more informal perhaps than formal, will eventually win since we must use technology to cause everyone to learn more, more economically and faster if everyone is to be economically productive and prosperous. Maintaining the status quo will only continue the existing win/lose society that we have with those who can learn in present school structure doing ok, while more and more students drop out, learn less, and fail to find a productive niche in the future.” – Ed Lyell, former member of the Colorado State Board of Education and Telecommunication Advisory Commission

“The question is flawed: Google will make intelligence different. As Carr himself suggests, Plato argued that reading and writing would make us stupid, and from the perspective of a preliterate, he was correct. Holding in your head information that is easily discoverable on Google will no longer be a mark of intelligence, but a side-show act. Being able to quickly and effectively discover information and solve problems, rather than do it “in your head,” will be the metric we use.” – Alex Halavais, vice president, Association of Internet Researchers

“What Google does do is simply to enable us to shift certain tasks to the network – we no longer need to rote-learn certain seldomly-used facts (the periodic table, the post code of Ballarat) if they’re only a search away, for example. That’s problematic, of course – we put an awful amount of trust in places such as Wikipedia where such information is stored, and in search engines like Google through which we retrieve it – but it doesn’t make us stupid, any more than having access to a library (or in fact, access to writing) makes us stupid. That said, I don’t know that the reverse is true, either: Google and the Net also don’t automatically make us smarter. By 2020, we will have even more access to even more information, using even more sophisticated search and retrieval tools – but how smartly we can make use of this potential depends on whether our media literacies and capacities have caught up, too.” – Axel Bruns, Associate Professor, Queensland University of Technology

“My ability to do mental arithmetic is worse than my grandfathers because I grew up in an era with pervasive personal calculators…. I am not stupid compared to my grandfather, but I believe the development of my brain has been changed by the availability of technology. The same will happen (or is happening) as a result of the Googleization of knowledge. People are becoming used to bite sized chunks of information that are compiled and sorted by an algorithm. This must be having an impact on our brains, but it is too simplistic to say that we are becoming stupid as a result of Google.” – Robert Acklund, Australian National University

“We become adept at using useful tools, and hence perfect new skills. Other skills may diminish. I agree with Carr that we may on the average become less patient, less willing to read through a long, linear text, but we may also become more adept at dealing with multiple factors…. Note that I said ‘less patient,’ which is not the same as ‘lower IQ.’ I suspect that emotional and personality changes will probably more marked than ‘intelligence’ changes.” – Larry Press, California State University, Dominguz Hills

Technology isn’t the problem here. It is people’s inherent character traits. The internet and search engines just enable people to be more of what they already are. If they are motivated to learn and shrewd, they will use new tools to explore in exciting new ways. If they are lazy or incapable of concentrating, they will find new ways to be distracted and goof off.

“The question is all about people’s choices. If we value introspection as a road to insight, if we believe that long experience with issues contributes to good judgment on those issues, if we (in short) want knowledge that search engines don’t give us, we’ll maintain our depth of thinking and Google will only enhance it. There is a trend, of course, toward instant analysis and knee-jerk responses to events that degrades a lot of writing and discussion. We can’t blame search engines for that…. What search engines do is provide more information, which we can use either to become dilettantes (Carr’s worry) or to bolster our knowledge around the edges and do fact-checking while we rely mostly on information we’ve gained in more robust ways for our core analyses. Google frees the time we used to spend pulling together the last 10% of facts we need to complete our research. I read Carr’s article when The Atlantic first published it, but I used a web search to pull it back up and review it before writing this response. Google is my friend.” – Andy Oram, editor and blogger, O’Reilly Media

“For people who are readers and who are willing to explore new sources and new arguments, we can only be made better by the kinds of searches we will be able to do. Of course, the kind of Googled future that I am concerned about is the one in which my every desire is anticipated, and my every fear avoided by my guardian Google. Even then, I might not be stupid, just not terribly interesting.” – Oscar Gandy, emeritus professor, University of Pennsylvania

“I don’t think having access to information can ever make anyone stupider. I don’t think an adult’s IQ can be influenced much either way by reading anything and I would guess that smart people will use the Internet for smart things and stupid people will use it for stupid things in the same way that smart people read literature and stupid people read crap fiction. On the whole, having easy access to more information will make society as a group smarter though.” – Sandra Kelly, market researcher, 3M Corporation

“The story of humankind is that of work substitution and human enhancement. The Neolithic revolution brought the substitution of some human physical work by animal work. The Industrial revolution brought more substitution of human physical work by machine work. The Digital revolution is implying a significant substitution of human brain work by computers and ICTs in general. Whenever a substitution has taken place, men have been able to focus on more qualitative tasks, entering a virtuous cycle: the more qualitative the tasks, the more his intelligence develops; and the more intelligent he gets, more qualitative tasks he can perform…. As obesity might be the side-effect of physical work substitution my machines, mental laziness can become the watermark of mental work substitution by computers, thus having a negative effect instead of a positive one.” – Ismael Peña-Lopez, lecturer at the Open University of Catalonia, School of Law and Political Science

“Well, of course, it depends on what one means by ‘stupid’ — I imagine that Google, and its as yet unimaginable new features and capabilities will both improve and decrease some of our human capabilities. Certainly it’s much easier to find out stuff, including historical, accurate, and true stuff, as well as entertaining, ironic, and creative stuff. It’s also making some folks lazier, less concerned about investing in the time and energy to arrive at conclusions, etc.” – Ron Rice, University of California, Santa Barbara

[Carr]

“Google isn’t making us stupid – but it is making many of us intellectually lazy. This has already become a big problem in university classrooms. For my undergrad majors in Communication Studies, Google may take over the hard work involved in finding good source material for written assignments. Unless pushed in the right direction, students will opt for the top 10 or 15 hits as their research strategy. And it’s the students most in need of research training who are the least likely to avail themselves of more sophisticated tools like Google Scholar. Like other major technologies, Google’s search functionality won’t push the human intellect in one predetermined direction. It will reinforce certain dispositions in the end-user: stronger intellects will use Google as a creative tool, while others will let Google do the thinking for them.” – David Ellis, York University, Toronto

It’s not Google’s fault if users create stupid queries.

“To be more precise, unthinking use of the Internet, and in particular untutored use of Google, has the ability to make us stupid, but that is not a foregone conclusion. More and more of us experience attention deficit, like Bruce Friedman in the Nicholas Carr article, but that alone does not stop us making good choices provided that the “factoids” of information are sound that we use to make out decisions. The potential for stupidity comes where we rely on Google (or Yahoo, or Bing, or any engine) to provide relevant information in response to poorly constructed queries, frequently one-word queries, and then base decisions or conclusions on those returned items.” – Peter Griffiths, former Head of Information at the Home Office within the Office of the Chief Information Officer, United Kingdom

“The problem isn’t Google; it’s what Google helps us find. For some, Google will let them find useless content that does not challenge their minds. But for others, Google will lead them to expect answers to questions, to explore the world, to see and think for themselves.” – Esther Dyson, longtime Internet expert and investor

“People are already using Google as an adjunct to their own memory. For example, I have a hunch about something, need facts to support, and Google comes through for me. Sometimes, I see I’m wrong, and I appreciate finding that out before I open my mouth.” – Craig Newmark, founder Craig’s List

“Google is a data access tool. Not all of that data is useful or correct. I suspect the amount of misleading data is increasing faster than the amount of correct data. There should also be a distinction made between data and information. Data is meaningless in the absence of an organizing context. That means that different people looking at the same data are likely to come to different conclusions. There is a big difference with what a world class artist can do with a paint brush as opposed to a monkey. In other words, the value of Google will depend on what the user brings to the game. The value of data is highly dependent on the quality of the question being asked.” – Robert Lunn, consultant, FocalPoint Analytics

The big struggle is over what kind of information Google and other search engines kick back to users. In the age of social media where users can be their own content creators it might get harder and harder to separate high-quality material from junk.

“Access to more information isn’t enough — the information needs to be correct, timely, and presented in a manner that enables the reader to learn from it. The current network is full of inaccurate, misleading, and biased information that often crowds out the valid information. People have not learned that ‘popular’ or ‘available’ information is not necessarily valid.”– Gene Spafford, Purdue University CERIAS, Association for Computing Machinery U.S. Public Policy Council

“If we take ‘Google’ to mean the complex social, economic and cultural phenomenon that is a massively interactive search and retrieval information system used by people and yet also using them to generate its data, I think Google will, at the very least, not make us smarter and probably will make us more stupid in the sense of being reliant on crude, generalised approximations of truth and information finding. Where the questions are easy, Google will therefore help; where the questions are complex, we will flounder.” – Matt Allen, former president of the Association of Internet Researchers and associate professor of internet studies at Curtin University in Australia

“The challenge is in separating that wheat from the chaff, as it always has been with any other source of mass information, which has been the case all the way back to ancient institutions like libraries. Those users (of Google, cable TV, or libraries) who can do so efficiently will beat the odds, becoming ‘smarter’ and making better choices. However, the unfortunately majority will continue to remain, as Carr says, stupid.” – Christopher Saunders, managing editor internetnews.com

“The problem with Google that is lurking just under the clean design home page is the “tragedy of the commons”: the link quality seems to go down every year. The link quality may actually not be going down but the signal to noise is getting worse as commercial schemes lead to more and more junk links.” – Glen Edens, former senior vice president and director at Sun Microsystems Laboratories, chief scientist Hewlett Packard

Literary intelligence is very much under threat.

“If one defines — or partially defines — IQ as literary intelligence, the ability to sit with a piece of textual material and analyze it for complex meaning and retain derived knowledge, then we are indeed in trouble. Literary culture is in trouble…. We are spending less time reading books, but the amount of pure information that we produce as a civilization continues to expand exponentially. That these trends are linked, that the rise of the latter is causing the decline of the former, is not impossible…. One could draw reassurance from today’s vibrant Web culture if the general surfing public, which is becoming more at home in this new medium, displayed a growing propensity for literate, critical thought. But take a careful look at the many blogs, post comments, Facebook pages, and online conversations that characterize today’s Web 2.0 environment…. This type of content generation, this method of ‘writing,’ is not only sub-literate, it may actually undermine the literary impulse…. Hours spent texting and e-mailing, according to this view, do not translate into improved writing or reading skills.” – Patrick Tucker, senior editor, The Futurist magazine

New literacies will be required to function in this world. In fact, the internet might change the very notion of what it means to be smart. Retrieval of good information will be prized. Maybe a race of “extreme Googlers” will come into being.

“The critical uncertainty here is whether people will learn and be taught the essential literacies necessary for thriving in the current infosphere: attention, participation, collaboration, crap detection, and network awareness are the ones I’m concentrating on. I have no reason to believe that people will be any less credulous, gullible, lazy, or prejudiced in ten years, and am not optimistic about the rate of change in our education systems, but it is clear to me that people are not going to be smarter without learning the ropes.” – Howard Rheingold, author of several prominent books on technology, teacher at Stanford University and University of California-Berkeley

“Google makes us simultaneously smarter and stupider. Got a question? With instant access to practically every piece of information ever known to humankind, we take for granted we’re only a quick web search away from the answer. Of course, that doesn’t mean we understand it. In the coming years we will have to continue to teach people to think critically so they can better understand the wealth of information available to them.” — Jeska Dzwigalski, Linden Lab

“We might imagine that in ten years, our definition of intelligence will look very different. By then, we might agree on “smart” as something like a ‘networked’ or ‘distributed’ intelligence where knowledge is our ability to piece together various and disparate bits of information into coherent and novel forms.” – Christine Greenhow, educational researcher, University of Minnesota and Yale Information and Society Project

“Human intellect will shift from the ability to retain knowledge towards the skills to discover the information i.e. a race of extreme Googlers (or whatever discovery tools come next). The world of information technology will be dominated by the algorithm designers and their librarian cohorts. Of course, the information they’re searching has to be right in the first place. And who decides that?” – Sam Michel, founder Chinwag, community for digital media practitioners in the United Kingdom

One new “literacy” that might help is the capacity to build and use social networks to help people solve problems.

“There’s no doubt that the internet is an extension of human intelligence, both individual and collective. But the extent to which it’s able to augment intelligence depends on how much people are able to make it conform to their needs. Being able to look up who starred in the 2nd season of the Tracey Ullman show on Wikipedia is the lowest form of intelligence augmentation; being able to build social networks and interactive software that helps you answer specific questions or enrich your intellectual life is much more powerful. This will matter even more as the internet becomes more pervasive. Already my iPhone functions as the external, silicon lobe of my brain. For it to help me become even smarter, it will need to be even more effective and flexible than it already is. What worries me is that device manufacturers and internet developers are more concerned with lock-in than they are with making people smarter. That means it will be a constant struggle for individuals to reclaim their intelligence from the networks they increasingly depend upon.” – Dylan Tweney, senior editor, Wired magazine

Nothing can be bad that delivers more information to people, more efficiently. It might be that some people lose their way in this world, but overall, societies will be substantially smarter.

“The Internet has facilitated orders of magnitude improvements in access to information. People now answer questions in a few moments that a couple of decades back they would not have bothered to ask, since getting the answer would have been impossibly difficult.” – John Pike, Director, globalsecurity.org

“Google is simply one step, albeit a major one, in the continuing continuum of how technology changes our generation and use of data, information, and knowledge that has been evolving for decades. As the data and information goes digital and new information is created, which is at an ever increasing rate, the resultant ability to evaluate, distill, coordinate, collaborate, problem solve only increases along a similar line. Where it may appear a ‘dumbing down’ has occurred on one hand, it is offset (I believe in multiples) by how we learn in new ways to learn, generate new knowledge, problem solve, and innovate.” — Mario Morino, Chairman, Venture Philanthropy Partners

Google itself and other search technologies will get better over time and that will help solve problems created by too-much-information and too-much-distraction.

“I’m optimistic that Google will get smarter by 2020 or will be replaced by a utility that is far better than Google. That tool will allow queries to trigger chains of high-quality information – much closer to knowledge than flood. Humans who are able to access these chains in high-speed, immersive ways will have more patters available to them that will aid decision-making. All of this optimism will only work out if the battle for the soul of the Internet is won by the right people – the people who believe that open, fast, networks are good for all of us.” – Susan Crawford, former member of President Obama’s National Economic Council, now on the law faculty at the University of Michigan

“If I am using Google to find an answer, it is very likely the answer I find will be on a message board in which other humans are collaboratively debating answers to questions. I will have to choose between the answer I like the best. Or it will force me to do more research to find more information. Google never breeds passivity or stupidity in me: It catalyzes me to explore further. And along the way I bump into more humans, more ideas and more answers.” – Joshua Fouts, Senior Fellow for Digital Media & Public Policy at the Center for the Study of the Presidency

The more we use the internet and search, the more dependent on it we will become.

“As the Internet gets more sophisticated it will enable a greater sense of empowerment among users. We will not be more stupid, but we will probably be more dependent upon it.” – Bernie Hogan, Oxford Internet Institute

Even in little ways, including in dinner table chitchat, Google can make people smarter.

[Family dinner conversations]

‘We know more than ever, and this makes us crazy.’

“The answer is really: both. Google has already made us smarter, able to make faster choices from more information. Children, to say nothing of adults, scientists and professionals in virtually every field, can seek and discover knowledge in ways and with scope and scale that was unfathomable before Google. Google has undoubtedly expanded our access to knowledge that can be experienced on a screen, or even processed through algorithms, or mapped. Yet Google has also made us careless too, or stupid when, for instance, Google driving directions don’t get us to the right place. It ahs confused and overwhelmed us with choices, and with sources that are not easily differentiated or verified. Perhaps it’s even alienated us from the physical world itself – from knowledge and intelligence that comes from seeing, touching, hearing, breathing and tasting life. From looking into someone’s eyes and having them look back into ours. Perhaps it’s made us impatient, or shortened our attention spans, or diminished our ability to understand long thoughts. It’s enlightened anxiety. We know more than ever, and this makes us crazy.” – Andrew Nachison, co-founder, We Media

A final thought: Maybe Google won’t make us more stupid, but it should make us more modest.

“There is and will be lots more to think about, and a lot more are thinking. No, not more stupid. Maybe more humble.” — Sheizaf Rafaeli, Center for the Study of the Information Society, University of Haifa