Introduction

Traditional offline political participation has long been the domain of certain groups: in particular, those with high levels of income and education. As opportunities for political activity have expanded with the internet, we wished to know whether these possibilities for online political engagement have potential to change that pattern. Does the internet bring in new kinds of activists by making it easier to take part politically, or does online engagement simply mirror the stratification seen in traditional offline civic activities?

To explore this question, we constructed separate scales measuring political participation on and off the internet, each containing five political activities that can be conducted either online or offline. These measures were:

|

Offline Activities |

Online Activities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

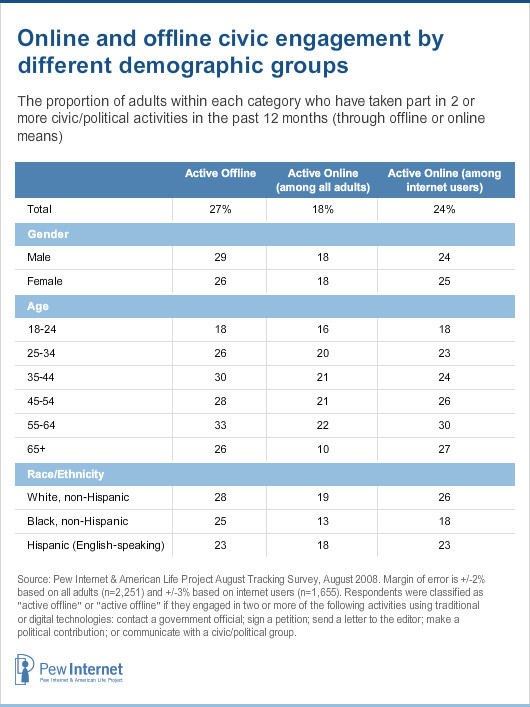

Respondents were classified as “active offline” or “active online” if they took part in two or more of the above activities during the preceding year. In all, 27% of American adults have taken part in two or more offline activities, while 18% (representing 24% of internet users) have engaged in two or more activities online. Interestingly, while there is a good deal of overlap between these two groups, those who are active online are more likely also to be active offline than vice versa: fully 73% of online activists are also active offline, compared to the 48% of offline activists who are also active online.

In addition to analyzing overall involvement along these two dimensions, we also considered the activities individually. In conducting this analysis, we sought to address the following questions:

- Is online political participation characterized by higher levels of activity by the well-educated and the affluent that have long been observed for offline political activities?

- To what extent is political engagement on blogs or social networking sites characterized by the same kinds of socio-economic effects as offline political engagement?

Online political activities are marked by the same high levels of stratification by income and education as their offline counterparts.

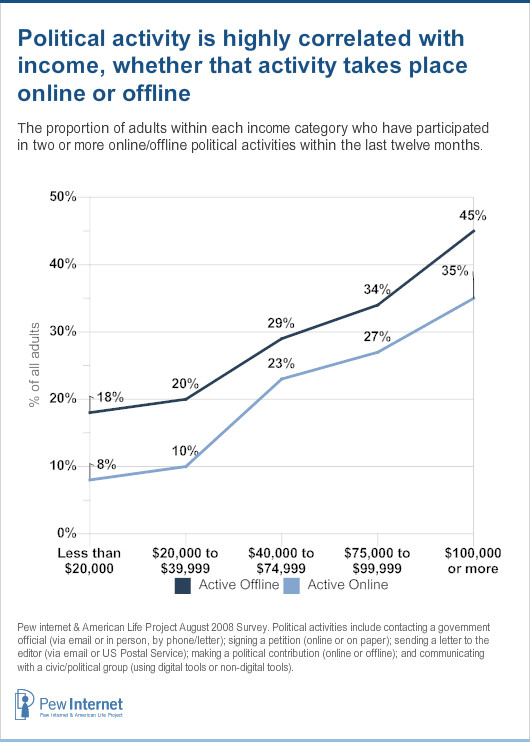

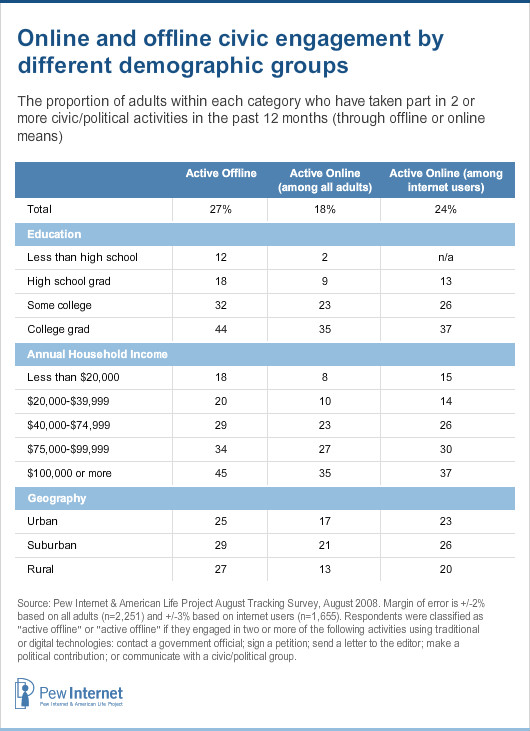

Nearly all traditional forms of civic activity are stratified by socio-economic status. That is, as income and educational levels increase, so do community involvement, political activism, and other types of civic engagement. This stratification holds not only for offline political acts but also for political participation online. One in five (18%) of those in the lowest income category (who earn less than $20,000 per year) take part in two or more offline activities, compared to 45% of those earning $100,000 or more per year, a difference of 27 percentage points. For online acts the difference between these two income groups is identical: 8% of those in the lowest income category as opposed to 35% for those in the highest income group.

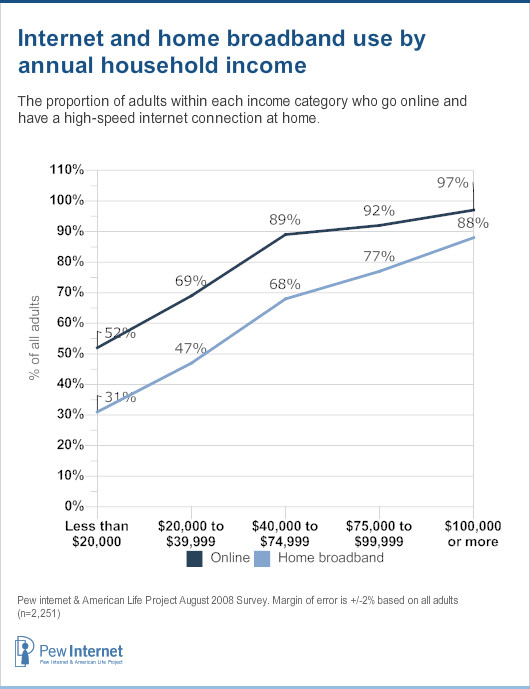

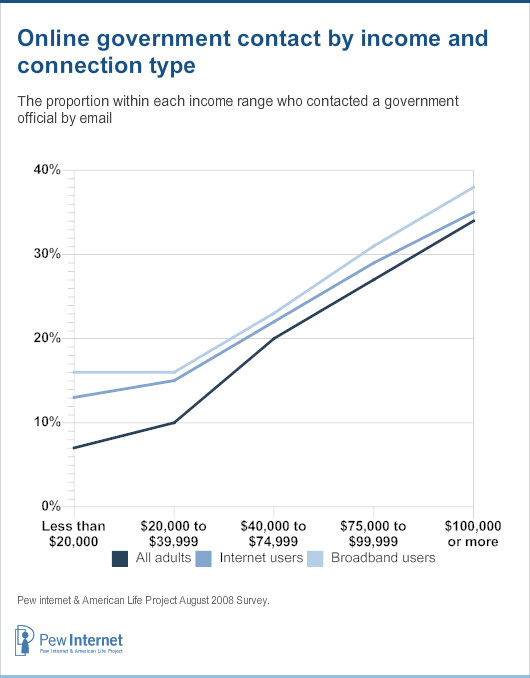

To be sure, access to the internet is part of the story. Those with higher levels of income are much more likely than those at lower levels of income both to use the internet and to have high-speed internet access at home. Moving from the lowest income category to the highest, internet usage rates rise from roughly 50% to more than 90%, and home broadband adoption rises from roughly one in three to nearly nine in ten. Thus, at least one factor responsible for lower levels of online political activity among those at the lower end of the income spectrum is lack of internet access.

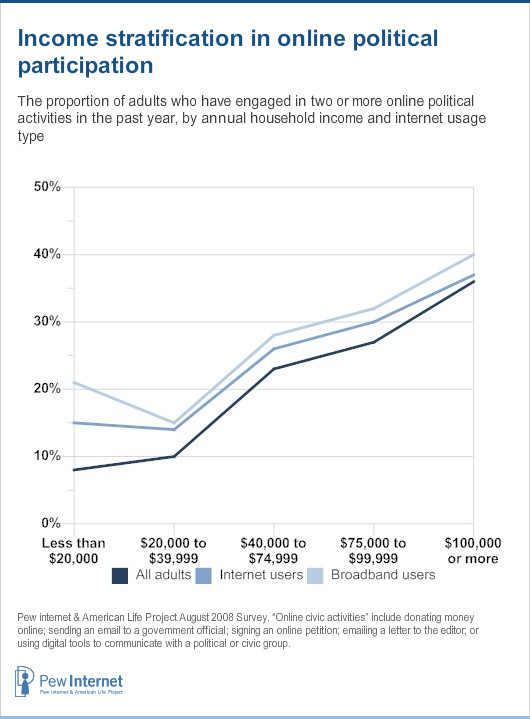

Lack of internet access is a partial, but not a full, explanation for the lesser levels of online political activity among those with low levels of income. When we consider three groups—all adults, internet users, and those have a home broadband connection—separately, we find that for all groups there is a strong relationship between online internet political activity and income.

A similar pattern holds for education as well. Those with higher levels of education (some college experience or a college degree) are much more likely to take part politically than are those with a high school diploma or less — regardless of whether that political activity occurs online or offline. Even among who use the internet, college experience is strongly associated with participation in online political activities.

In short, income and education have the same relationship to online and offline political activity, and there is no evidence that Web-based political participation fundamentally alters the long-established association between offline political participation and these socio-economic factors.

Compared to income and education, the relationship between age and these political activities is somewhat more complex. For offline political participation, young adults (those ages 18-24) are the group that is least likely to take part. In contrast, when it comes to online political activity, for the population as a whole, the participatory deficit of young adults is less pronounced, and it is seniors who are the least active group. This relationship, however, is largely a function of very high rates of internet use among young adults. When we consider just the internet users within each age cohort, young adults are again the least likely group to engage in political acts online, and the relatively small group of internet users who are 65 and over are quite active. In other words, the underrepresentation of the young with respect to political participation over the internet is related to their greater likelihood to be internet users and not necessarily to any innate propensity to use the internet politically once online.

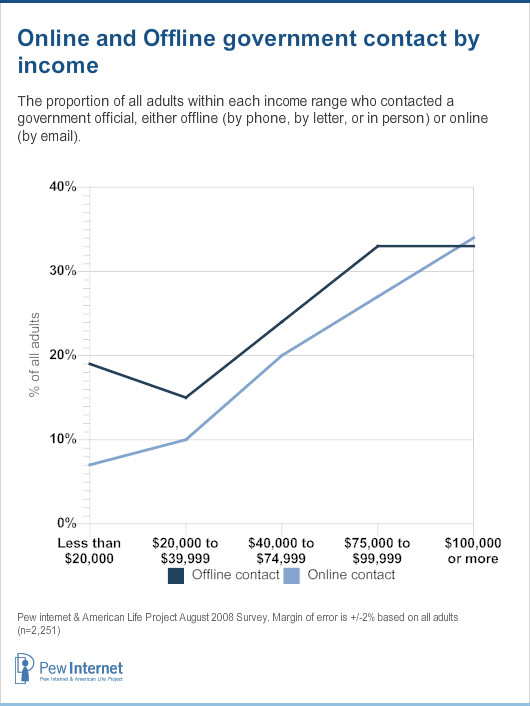

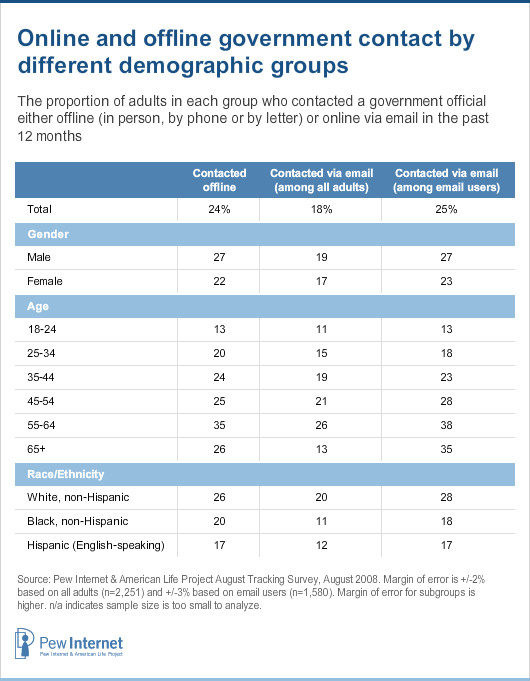

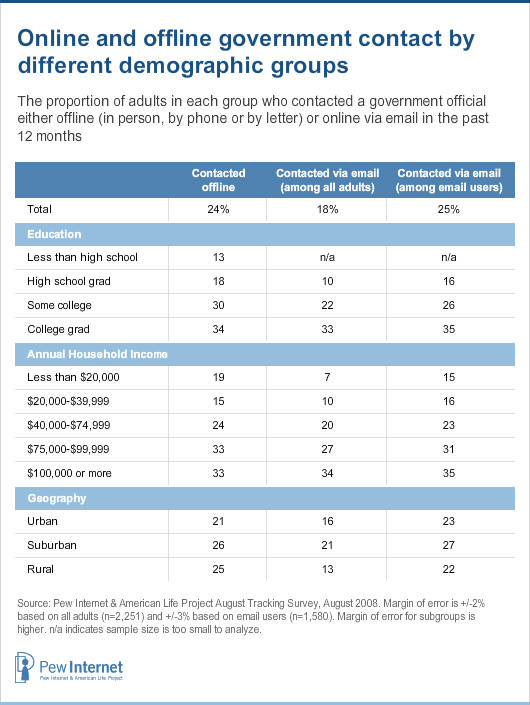

The patterns are similar for specific activities—for instance, contacting a government official directly about an important issue. There is a high correlation with income for both online and offline methods of contacting government officials. Indeed, the difference between the highest and lowest income groups is actually higher for contacting a government official by email than it is for contacting a government official by phone or by letter (27 percentage points for online contact, compared to 14 percentage points for offline contact).

As with the broader measure of online political participation discussed earlier, low rates of internet access among lower-income Americans tell part, but only part, of the story. Even when we focus on those respondents who go online or have a high-speed connection at home, those at the high end of the income scale are still much more likely than those at the bottom to contact a government official via email.

When we look at the relationship of age and education to contacting a government official, we see patterns similar to what we saw earlier for overall online and offline civic involvement. Education is highly correlated with both online and offline government contact — even among internet users. With respect to age, the relative likelihood of young adults to email a government official is largely a function of their high rates of internet use: within the online population, those aged 65 and older are roughly three times more likely to contact a government official via email as are those aged 18 to 24 (35% vs. 13%).

The second individual activity that drew our interest is donating money to a political candidate, party or other political organization. Because it offers the potential to bring new voices into the political system, we were particularly interested in investigating the making small donations online.

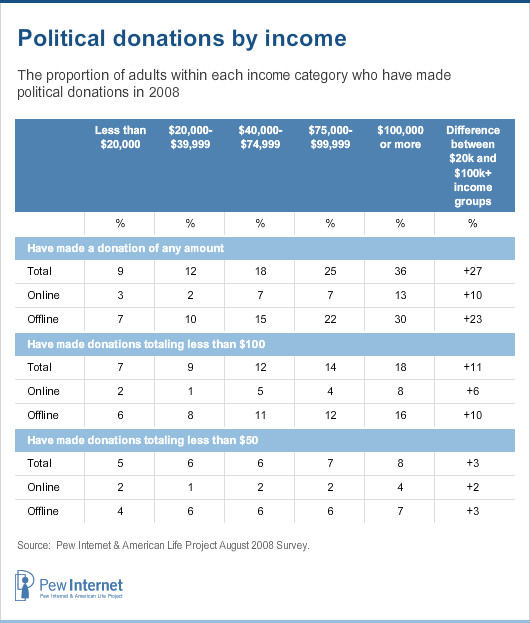

As with the other activities we have examined, the likelihood of making political contributions rises steadily with income. Just 9% of those with incomes under $20,000 per year made one or more political contributions in 2008, compared to more than one-third (36%) of those with incomes over $100,000—a difference of 27 percentage points. As might be expected, this difference shrinks as the amount donated decreases. For donations under $100, the difference between the lowest and highest income groups is 11 percentage points. For donations of less than $50 the difference between these two groups is substantially smaller: 5% of those in the lowest income group, compared to 8% of those in the highest, made a small donation of $50 or less.

Interestingly, these differences do not exhibit a great deal of variation for online versus offline donations. The difference between the lowest and highest income categories with respect to making small contributions of no more than $50 is nearly identical for online versus offline donations—2% versus 3%. In other words, the ability to make small donations online does not in and of itself appear to be drawing large numbers of low-income small contributors into the political system. However, it is important to reiterate that this survey was conducted in August, prior to Barack Obama’s autumn online fundraising push, and should be interpreted accordingly.