Introduction

Like many technical innovations, the internet was greeted enthusiastically by those who thought it would “change everything” when it comes to democratic governance. Among its predicted salutary effects is the capacity of the internet to permit ordinary citizens to short-circuit political elites and deal directly with one another and public officials; to foster deliberation, enhance trust, and create community; and—of special interest to us—to facilitate political participation.

Other observers have been doubtful about the expected benefits, pointing out that every technological advance has been greeted with the inflated expectations that faster transportation and easier communication will beget citizen empowerment and civic renewal. This insight leads to the more cautious assessment that, rather than revolutionizing democratic politics, it would end up being more of the same and reinforcing established political patterns and familiar political elites. Even more sober were those who feared that, far from cultivating social capital, the internet would foster undemocratic tendencies: greater political fragmentation, “hacktivism,” and incivility.

For a variety of reasons, the internet might be expected to raise participation: The interactive capacities of the internet allow certain forms of political activity to be conducted more easily; vast amounts of political information available on the internet could have the effect of lowering the costs of acquiring political knowledge and stimulating political interest; the capacities of the internet facilitate mobilization to take political action. However, it is widely known that, with respect to a variety of politically relevant characteristics, political activists are different from the public at large. And more participation does not necessarily mean that participants are socially and economically more diverse. For one thing, internet access is far from universal among American adults, a phenomenon widely known as the “digital divide,” and the contours of the digital divide reflect in certain ways the shape of participatory input. Moreover, access to the internet does not necessarily mean use of the internet for political activity. Therefore, it seems important to investigate the extent to which online political and civic activities ameliorate, reflect, or even exaggerate the long-standing tendencies in offline political activity.

There are several ways in which digital tools might facilitate political participation. For one thing, several forms of political activity—including making donations, forming a group of like-minded people, contacting public officials, and registering to vote—are simply easier on the internet. Because activity can be undertaken any time of day or night from any locale with a computer and an internet connection, the costs of taking part are reduced. The capacities of the internet are also suited to facilitate the process of the formation of political groups. By making it so cheap to communicate with a large number of potential supporters, the internet reduces the costs of getting a group off the ground. The internet reduces almost to zero the additional costs of seeking to organize many rather than few potential adherents even if they are widely scattered geographically.

Perhaps as important in fostering political activity directly is the wealth of political information available to those who have access to the internet. Just about every offline source of political information is now on the Web, usually without charge: governments at all levels along with such visible public officials as members of the House and Senate, governors, and mayors of large cities; candidates for public office, political parties and organizations; print sources of political news including newspapers, wire services, newsmagazines as well as broadcast news sources that mix print material with audio and video clips. In addition, indigenous to the internet are various potentially politicizing experiences. For example, online conversations, often about political subjects, in a variety of internet venues are in most ways analogous to the political discussions that routinely take place over the dinner table or at the water cooler but have the capacity to bring together large numbers of participants spread over vast distances.

The third mechanism by which the internet might enhance political activity follows directly from its capacity to communicate with large numbers of geographically dispersed people at little cost. Candidates, parties, and political organizations do not simply use the internet as a way or disseminating information, they also use its capabilities to communicate with adherents and sympathizers and to recruit them to take political action—either on or offline.

This report examines the state of civic engagement in America. One major goal of the survey was to compare certain offline political activities—for example, signing petitions or making donations—with their online counterparts. Another objective was to investigate the possibility of political and civic engagement through blogs and social networking sites. This survey allows us to compare the offline and online worlds in a variety of ways:

- How and to what extent are digital and online tools being used by Americans to communicate with civic groups, or to engage with the political system?

- Are online avenues for political activity bringing new voices and groups into civic and political life?

- Where do relatively new venues for civic debate such as blogs or social networking sites fit into the overall spectrum of civic and political involvement? Are these tools bringing new voices into the broader civic debate?

All these results come from a national telephone survey of 2,251 American adults (including 1,655 internet users) conducted between August 12 and August 31, 2008. This sample was gathered entirely on landline phones. There was no extra sample of cell-phone users, who tend to be younger and slightly more likely to be internet users.

Political Participation: Nearly two-thirds of all Americans have participated in some form of political activity in the past year. Just under one-fifth engaged in four or more political acts on a scale of eleven different activities.

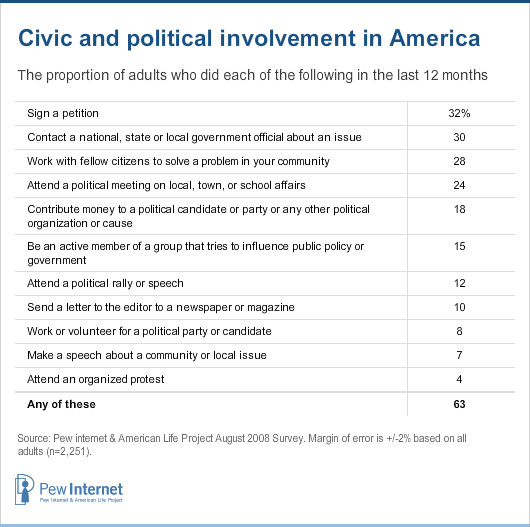

In attempting to measure the state of political participation in America, we asked about participation in eleven forms of political activity ranging from working with fellow citizens to solve local problems, to participating actively in organizations that try to influence public policy, to volunteering for a political party or candidate.2 Fully 63% of all adults have done at least one of the following eleven activities over the previous twelve months:

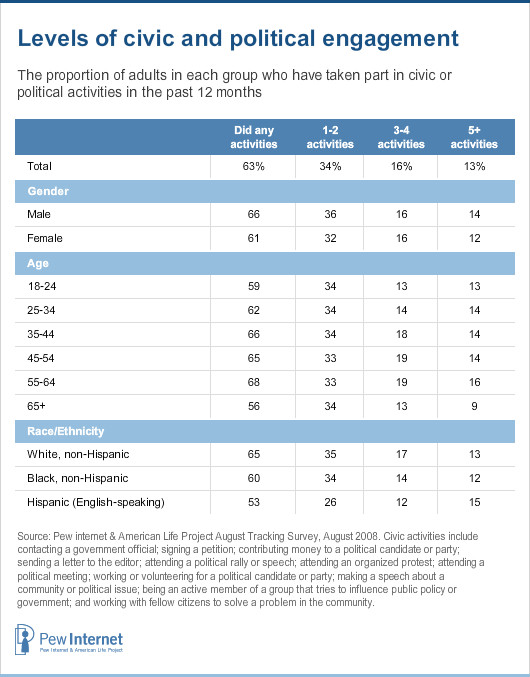

Taken together, 34% of all adults did one or two of the above activities this year, while an additional 16% took part in 3-4 activities. A highly-engaged 13% of Americans have taken part in five or more of these activities in the last year.

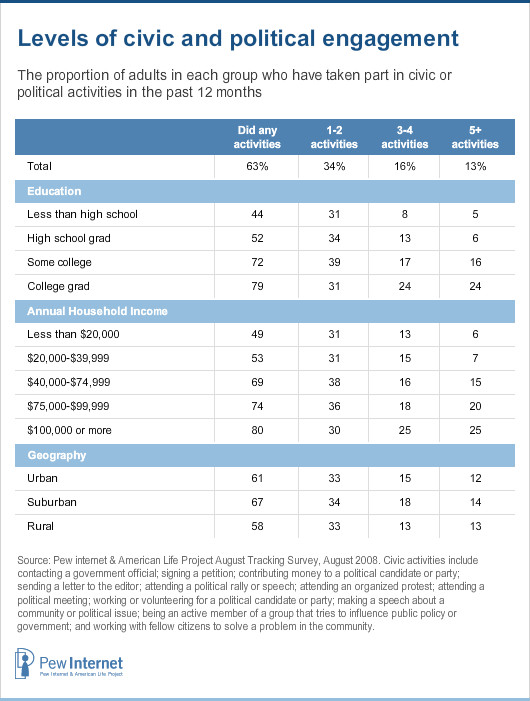

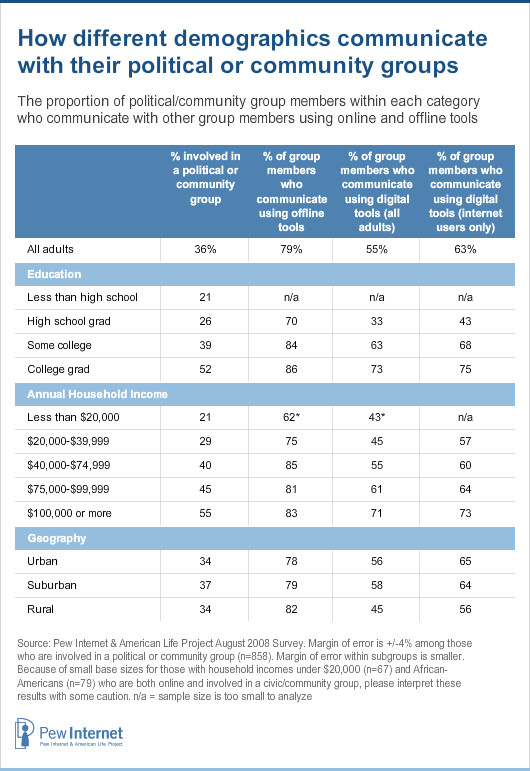

Our results are consistent with previous research in finding that individuals with high levels of income and education tend to be much more likely to take part politically. As income and education levels increase, so does participation in a wide range of political activities, in particular, working with fellow citizens to solve community problems; attending political meetings; taking part in a civic or political group; attending a political rally or speech; working or volunteering for a political party or candidate; making political contributions; or getting in touch with public officials.

When we consider individual political acts, we sometimes find that a particular subgroup is especially active. For example, those under 30 and English-speaking Hispanics were especially likely to have attended an organized protest in the previous twelve months; suburbanites were more likely to have attended a political meeting on local, town, or school affairs; and fifty and sixty-somethings were especially likely to have contacted a government official. Otherwise, the group differences on the basis of gender, age, race or ethnicity, kind of community are much less substantial than the differences on the basis of income or, especially, education.

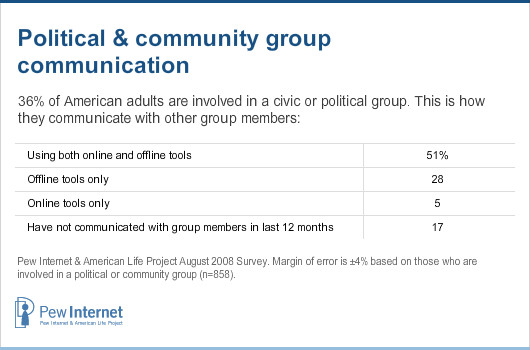

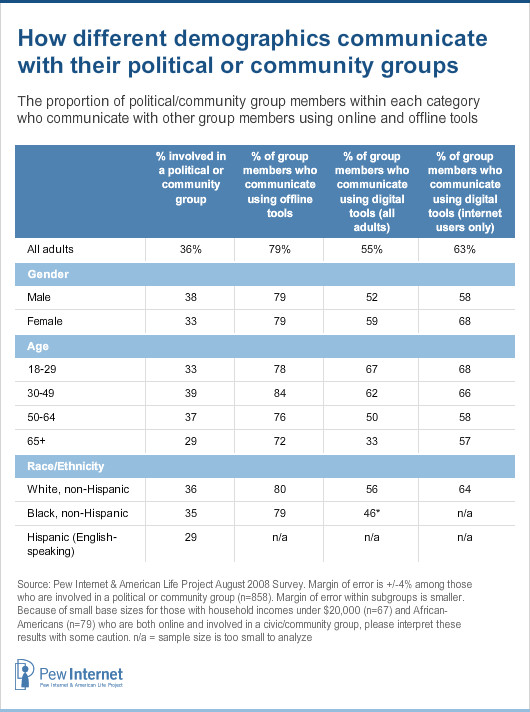

More than a third of Americans (36%) have gotten involved in a political or community group in the past year by doing at least one of the following: working with fellow citizens to solve a local problem; being active in a group that tries to influence public policy or government; or working or volunteering for a political party or candidate. Fully 83% of those who are involved in such groups have communicated with other group members in the past 12 months and they use a range of approaches to keep in touch. Some 51% indicated that they communicated with other group members online (using tools such as email, text messaging, or the group’s website) as well as offline (using face-to-face meetings, letters/newsletters or phone calls). An additional 5% communicated using only online tools such as email, and another 28% interacted with group members using only offline means: in person, by phone, or through letters or newsletters.

Face-to-face meetings and telephone communication are the two single most common ways that members of community/political groups communicate with fellow group members. Among those individuals who are involved in a community or political group:

- 63% have communicated with other group members by having face-to-face meetings

- 60% have done so by telephone

- 35% have done so through print letter or group newsletter

Nearly nine in ten community or political group members go online, and email has emerged as a key communications tool for facilitating group communications. Fully 57% of wired members of a community or political group communicate with other group members via email — making email nearly as popular as face-to-face meetings and telephone communication. Furthermore, among those who are involved in a political or community group:

- 32% of internet users have communicated with group members by using the group’s website, and 10% have done so via instant messaging.

- 24% of social networkers have communicated with group members by using a social networking site.

- 17% of cell phone owners have communicated with group members by text messaging on a cell phone or PDA.

Communication: Nearly half of all Americans have expressed their opinions in a public forum on topics that are important to them, and blogs and social networking sites provide new opportunities for political engagement.

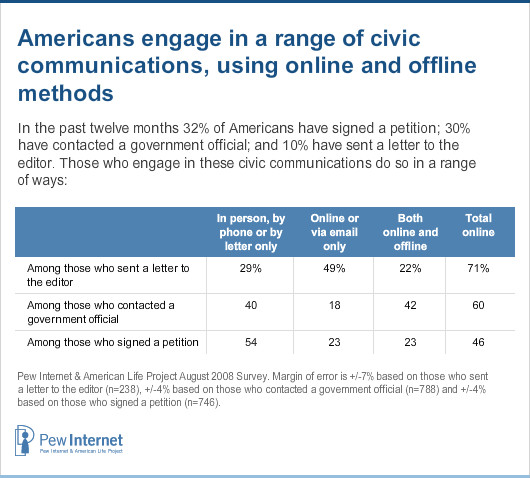

In addition to participating directly in civic groups or activities, 49% of Americans have spoken out about an issue that is important to them in the past year by contacting a government agency or official, signing a petition, writing a letter to the editor or calling into a radio or television show. Over this time period:

- 32% of all adults have signed a petition. One-quarter (25%) of all adults have signed a paper petition, while 19% of internet users have signed a petition online.

- 30% of all adults have contacted a national, state, or local government official about an issue that is important to them. One-quarter (24%) of all adults have done so in person, by phone or by letter, while 25% of internet users have done so via email.

- 10% of all adults have sent a “letter to the editor” to a newspaper or magazine. Five percent of all adults have sent a physical letter to the editor through the US Postal Service, while 10% of internet users have done so via email.

- 8% of all adults have called into a live radio or TV show to express an opinion.

As the numbers above indicate, many people engage in civic communications using multiple channels—for instance, they may sign a paper petition for one issue and an online petition for another—and certain types of communications are especially likely to take place online. Letters to the editor are most commonly sent via email: among those who sent a letter to the editor using any delivery method, fully 49% did so online or via email, and an additional 22% did so both electronically and via the US Postal Service. In contrast, among those who have signed a petition more than half signed a paper petition only.

Among those Americans who have done at least one of these activities in the last year, fully 54% did so online—whether by signing an online petition, sending an email to a government official or sending a letter to the editor via email—while 81% did so offline.

Interestingly, the method citizens use to contact government officials appears to have little relationship to whether or not they receive a response, or whether they are satisfied with the result of their communication. Among those who contacted a government official in person, by phone, or by letter, 67% said they received a response to their query, a rate little different from the 64% who received a response after sending a government official an email.

Similarly, 66% of individuals who contacted a government official by phone, letter or in person were satisfied with the response they received, once again little different from the 63% who were satisfied with the response to their email communication.

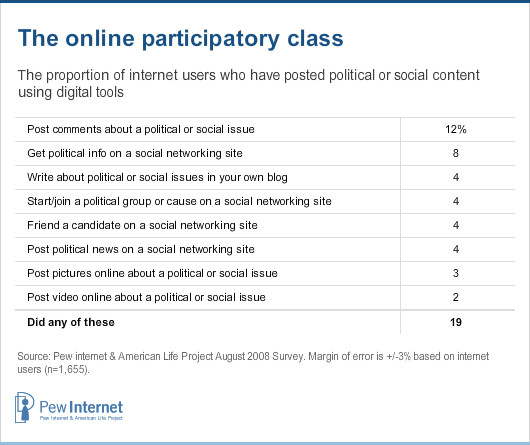

Today’s wired citizens are offered a range of other avenues for civic involvement. With the rise of the blogosphere, social networking sites and other online tools, interested citizens can now take part in the online community of political and civic activists by posting their own commentary on social issues online. Indeed, 15% of internet users (representing 11% of all adults) have gone online to add to the political discussion in this way. One in eight internet users (12%) have posted comments on a website or blog about a political or social issue, 3% have posted pictures, 2% have posted video content and 4% have posted political content for their friends to read on an online social network. In addition, 31% of bloggers have used their blog to explore political or social issues. Since 13% of internet users maintain an online journal or blog, that means that 4% of internet users have blogged about political or social issues.

In addition to the possibilities for posting content on blogs and other websites, social networking sites have also become fertile ground for engagement with the political process. As of August 2008, 33% of internet users had a profile on a social networking site and 31% of these social network site members had engaged in activities with a civic or political focus (such as joining a political cause, or getting campaign or candidate information). That works out to 10% of all internet users who used a social networking site for some form of political or civic engagement.

Taking these two activities (posting content online and engaging politically on a social networking site) together, fully 19% of all internet users can be considered members of the online “participatory class”.

As we shall see, the nature of this online activism differs in some important respects from the other civic or political activities discussed in this report.

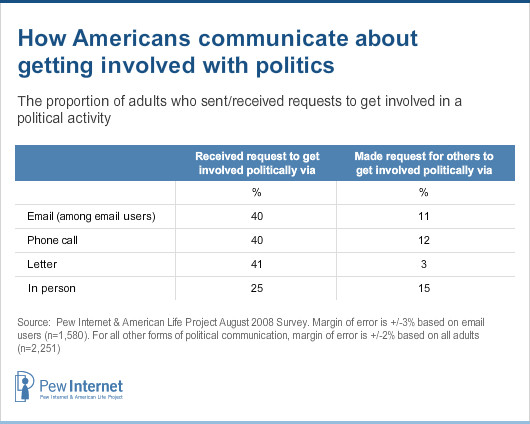

Mobilization: 40% of email users received requests by email to take part in a political activity in 2008, and an additional one in ten used email to ask others to get involved in politics.

In 2008, Americans were frequently asked — and, in turn, asked others — to take part in political activities. Two in five adults received at least occasional requests to take part politically via email, telephone, or letter, while an additional 25% were asked to do so in person. Although very few (just 3%) sent letters asking others to take part politically, roughly one in ten sent emails or made phone calls asking others to get involved, and 15% did so in person.

For a small share of the public, email functioned in 2008 as a key tool for daily political communication and mobilization. Five percent of email users say they receive emails on a daily basis asking them to get involved in a political activity, and an additional 7% receive such emails every few days. Far fewer Americans receive phone calls (1% get phone calls on a daily basis, and 3% do so every few days), letters (1% daily, 3% every few days) or in-person requests (1% daily, 1% every few days) to take some form of political action.

As of August 2008, 7% of internet users had gone online to donate to a political candidate or organization. Supporters of the Democratic Party led the way in online giving.

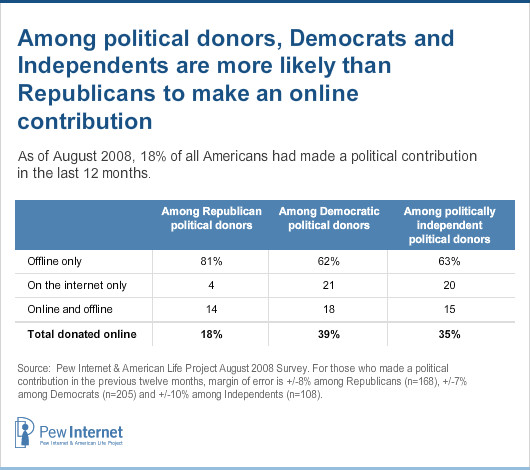

As of August 2008, just under one in five (18%) Americans had contributed money to a political candidate, party or other political organization or cause. Among these political donors, more than two-thirds (69%) made a contribution solely through offline means—over the phone, by mail, or in person. Three in ten went online to make a political donation—15% donated money only over the internet, while an additional 15% donated both online and offline. Put another way, 7% of internet users (representing 6% of all adults) made an online political contribution by the summer of 2008.3

In our August sample, Democrats and Republicans were equally likely make a political contribution—23% of Republicans and 24% of Democrats did so. However, Democratic donors were far more likely than their Republican counterparts to donate money over the internet. In total, 39% of Democrats who donated money this election cycle did so online, compared to 18% of Republicans. Indeed, fully 21% of Democrats who donated money this election cycle did so only online. Just 4% of Republican donors relied exclusively on the internet to make political contributions.

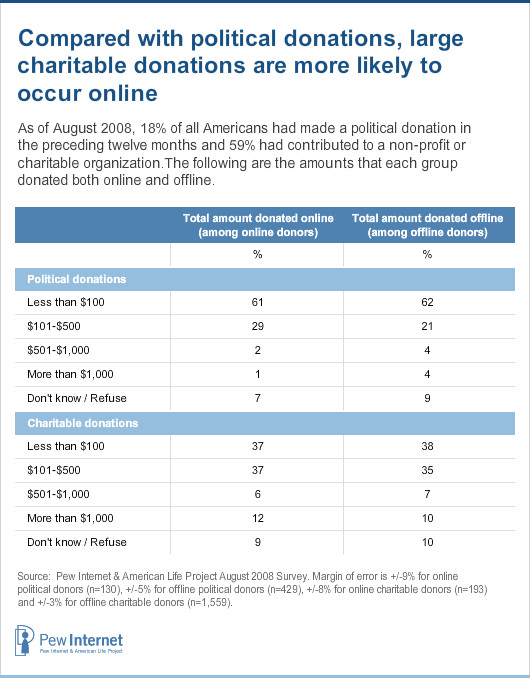

Compared to political donors, charitable donors are less likely to go online to make their contributions, but charitable donors are more likely to make a large contribution over the internet.

Fully 80% of all Americans have made a contribution to a political, religious, or charitable organization in the past year, with religious and charitable giving being particularly widespread. Within the last twelve months, six in ten Americans (59%) contributed money, property or other items to a church, synagogue, mosque or other place of worship while two-thirds (67%) contributed to a charity or non-profit organization other than their place of worship.

Compared to political donations, donations to non-profit and charitable organizations (excluding places of worship) are far more likely to take place offline. Among those who contributed to a non-profit or charitable organization in the past year, just 12% did so online (In comparison, 30% of political donors gave money online.) Still, because there are a large number of charitable donors within the population, this means that fully 11% of internet users (representing 9% of all adults) went online to donate money to a non-profit or charitable organization in the past year.

While much was made in this election cycle of the phenomenon of the “small online donor,” online and offline political contributors in our survey were equally likely to have contributed small amounts of money to a political party or candidate or any other political organization or cause. Among those who made at least one political contribution online, 35% contributed a total of $50 or less while 26% contributed between $50 and $100. This is nearly identical to the rates for those who made an offline political donation: within this group, 35% donated less than $50, and 27% donated between $50 and $100.

Although online and offline political donors do not differ significantly at the low end of the contribution scale, larger political contributions are confined primarily to the offline world. Among political donors who gave money online, just 3% said they had contributed more than $500 online in the past year. By contrast, 8% of those who had donated money to a candidate or campaign offline said they had contributed in excess of $500 in the preceding year.

This tendency for large political donations to occur offline is especially interesting when compared to donations to non-profit institutions or charitable causes. Those who make charitable donations are less likely one the whole to make online donations than are political donors. Nevertheless, in contrast to political donors, who are less likely to make a large contribution if they are contributing on the internet, charitable contributors are equally likely to make large contributions regardless of whether they are donating online or offline. Among those who made charitable donations online about one in six (17%) contributed more than $500, and 12% contributed more than $1000. For offline charitable donors, the analogous figures are nearly identical—18% of offline charitable donors contributed more than $500 and 10% contributed in excess of $1000. For whatever reason, the tendency of political donors to make large contributions offline is not apparent when it comes to charitable giving.