Teenagers’ lives are filled with writing. All teens write for school, and 93% of teens say they write for their own pleasure. Most notably, the vast majority of teens have eagerly embraced written communication with their peers as they share messages on their social network pages, in emails and instant messages online, and through fast-paced thumb choreography on their cell phones. Parents believe that their children write more as teens than they did at that age.

This raises a major question: What, if anything, connects the formal writing teens do and the informal e-communication they exchange on digital screens? A considerable number of educators and children’s advocates worry that James Billington, the Librarian of Congress, was right when he recently suggested that young Americans’ electronic communication might be damaging “the basic unit of human thought – the sentence.”1 They are concerned that the quality of writing by young Americans is being degraded by their electronic communication, with its carefree spelling, lax punctuation and grammar, and its acronym shortcuts. Others wonder if this return to text-driven communication is instead inspiring new appreciation for writing among teens.

While the debate about the relationship between e-communication and formal writing is on-going, few have systematically talked to teens to see what they have to say about the state of writing in their lives. Responding to this information gap, the Pew Internet & American Life Project and National Commission on Writing conducted a national telephone survey and focus groups to see what teens and their parents say about the role and impact of technological writing on both in-school and out-of-school writing. The report that follows looks at teens’ basic definition of writing, explores the various kinds of writing they do, seeks their assessment about what impact e-communication has on their writing, and probes for their guidance about how writing instruction might be improved.

At the core, the digital age presents a paradox. Most teenagers spend a considerable amount of their life composing texts, but they do not think that a lot of the material they create electronically is real writing. The act of exchanging emails, instant messages, texts, and social network posts is communication that carries the same weight to teens as phone calls and between-class hallway greetings.

At the same time that teens disassociate e-communication with “writing,” they also strongly believe that good writing is a critical skill to achieving success – and their parents agree. Moreover, teens are filled with insights and critiques of the current state of writing instruction as well as ideas about how to make in-school writing instruction better and more useful.

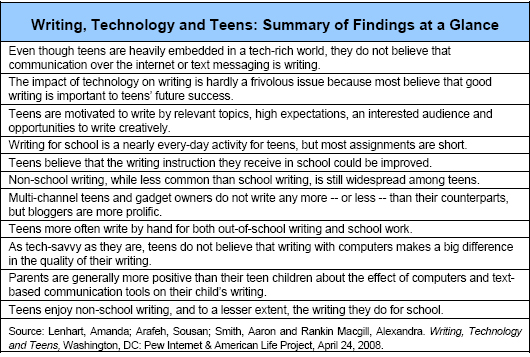

Even though teens are heavily embedded in a tech-rich world, they do not believe that communication over the internet or text messaging is writing.

The main reason teens use the internet and cell phones is to exploit their communication features.2 3 Yet despite the nearly ubiquitous use of these tools by teens, they see an important distinction between the “writing” they do for school and outside of school for personal reasons, and the “communication” they enjoy via instant messaging, phone text messaging, email and social networking sites.

- 85% of teens ages 12-17 engage at least occasionally in some form of electronic personal communication, which includes text messaging, sending email or instant messages, or posting comments on social networking sites.

- 60% of teens do not think of these electronic texts as “writing.”

Teens generally do not believe that technology negatively influences the quality of their writing, but they do acknowledge that the informal styles of writing that mark the use of these text-based technologies for many teens do occasionally filter into their school work. Overall, nearly two-thirds of teens (64%) say they incorporate some informal styles from their text-based communications into their writing at school.

- 50% of teens say they sometimes use informal writing styles instead of proper capitalization and punctuation in their school assignments;

- 38% say they have used text shortcuts in school work such as “LOL” (which stands for “laugh out loud”);

- 25% have used emoticons (symbols like smiley faces 🙂 ) in school work.

For more information on teens and electronic communication, please see Part 4: Electronic Communication starting on page 21.

The impact of technology on writing is hardly a frivolous issue because most believe that good writing is important to teens’ future success.

Both teens and their parents say that good writing is an essential skill for later success in life.

- 83% of parents of teens feel there is a greater need to write well today than there was 20 years ago.

- 86% of teens believe good writing is important to success in life – some 56% describe it as essential and another 30% describe it as important.

Parents also believe that their children write more now than they did when they were teens.

- 48% of teenagers’ parents believe that their child is writing more than the parent did during their teen years; 31% say their child is writing less; and 20% believe it is about the same now as in the past.

Recognition of the importance of good writing is particularly high in black households and among families with lower levels of education.

- 94% of black parents say that good writing skills are more important now than in the past, compared with 82% of white parents and 79% of English-speaking Hispanic parents.

- 88% of parents with a high school degree or less say that writing is more important in today’s world, compared with 80% of parents with at least some college experience.

For more information on this topic, please visit Part 6: Parental Attitudes toward Writing and Technology starting on page 36 and Part 7: The Way Teens See Their Writing and What Would Improve It on page 42.

Teens are motivated to write by relevant topics, high expectations, an interested audience and opportunities to write creatively.

Teens write for a variety of reasons—as part of a school assignment, to get a good grade, to stay in touch with friends, to share their artistic creations with others or simply to put their thoughts to paper (whether virtual or otherwise). In our focus groups, teens said they are motivated to write when they can select topics that are relevant to their lives and interests, and report greater enjoyment of school writing when they have the opportunity to write creatively. Having teachers or other adults who challenge them, present them with interesting curricula and give them detailed feedback also serves as a motivator for teens. Teens also report writing for an audience motivates them to write and write well.

For more on why teens write and what motivates them, please see Part 8: What Teens Tell Us Encourages Them to Write, which starts on page 51.

Writing for school is a nearly every-day activity for teens, but most assignments are short.

Most teens write something nearly every day for school, but the average writing assignment is a paragraph to one page in length.

- 50% of teens say their school work requires writing every day; 35% say they write several times a week. The remaining 15% of teens write less often for school.

- 82% of teens report that their typical school writing assignment is a paragraph to one page in length.

- White teens are significantly more likely than English-speaking Hispanic teens (but not blacks) to create presentations for school (72% of whites and 58% of Hispanics do this).

The internet is also a primary source for research done at or for school. 94% of teens use the internet at least occasionally to do research for school, and nearly half (48%) report doing so once a week or more often.

For more information, please visit Part 3: Teens and Their Writing Habits on page 10 in the main report.

Teens believe that the writing instruction they receive in school could be improved.

Most teens feel that additional instruction and focus on writing in school would help improve their writing even further. Our survey asked teens whether their writing skills would be improved by two potential changes to their school curricula: teachers having them spend more time writing in class, and teachers using more computer-based tools (such as games, writing help programs or websites, or multimedia) to teach writing.

Overall, 82% of teens feel that additional in-class writing time would improve their writing abilities and 78% feel the same way about their teachers using computer-based writing tools.

For more on this topic please see Part 7: The Way Teens See Their Writing and What Would Improve It starting on page 42.

Non-school writing, while less common than school writing, is still widespread among teens.

Outside of a dedicated few, non-school writing is done less often than school writing, and varies a bit by gender and race/ethnicity. Boys are the least likely to write for personal enjoyment outside of school. Girls and black teens are more likely to keep a journal than other teens. Black teens are also more likely to write music or lyrics on their own time.

- 47% of black teens write in a journal, compared with 31% of white teens.

- 37% of black teens write music or lyrics, while 23% of white teens do.

- 49% of girls keep a journal; 20% of boys do.

- 26% of boys say they never write for personal enjoyment outside of school.

For more on non-school writing, please see Part 3: Teens and Their Writing Habits on page 10 and Part 8: What Teens Tell Us Encourages Them to Write starting on page 51.

Multi-channel teens and gadget owners do not write any more – or less –than their counterparts, but bloggers are more prolific.

Teens who communicate frequently with friends, and teens who own more technology tools such as computers or cell phones do not write more for school or for themselves than less communicative and less gadget-rich teens. Teen bloggers, however, are prolific writers online and offline.

- 47% of teen bloggers write outside of school for personal reasons several times a week or more compared to 33% of teens without blogs.

- 65% of teen bloggers believe that writing is essential to later success in life; 53% of non-bloggers say the same.

For more on teens and electronic communication, please see Part 4: Electronic Communication on page 21 in the full report.

Teens more often write by hand for both out-of-school writing and school work.

Most teens mix and match longhand and computers based on tool availability, assignment requirements and personal preference. When teens write they report that they most often write by hand, though they also often write using computers as well. Out-of-school personal writing is more likely than school writing to be done by hand, but longhand is the more common mode for both purposes.

- 72% of teens say they usually (but not exclusively) write the material they are composing for their personal enjoyment outside of school by hand; 65% say they usually write their school assignments by hand.

For more on the technologies teens use for writing, please see Part 3: Teens and Their Writing Habits starting on page 10.

As tech-savvy as they are, teens do not believe that writing with computers makes a big difference in the quality of their writing.

Teens appreciate the ability to revise and edit easily on a computer, but do not feel that use of computers makes their writing better or improves the quality of their ideas.

- 15% of teens say their internet-based writing of materials such as emails and instant messages has helped improve their overall writing while 11% say it has harmed their writing. Some 73% of teens say this kind of writing makes no difference to their school writing.

- 17% of teens say their internet-based writing has helped the personal writing they do that is not for school, while 6% say it has made their personal writing worse. Some 77% believe this kind of writing makes no difference to their personal writing.

When it comes to using technology for school or non-school writing, teens believe that when they use computers to write they are more inclined to edit and revise their texts (57% say that).

For more on teen attitudes toward technologies’ influence on their writing, please see Part 7: The Way Teens See Their Writing and What Would Improve It, which begins on page 42.

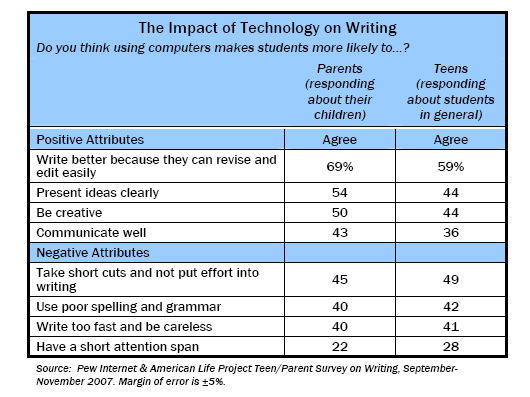

Parents are generally more positive than their teen children about the effect of computers and text-based communication tools on their child’s writing.

Parents are somewhat more likely to believe that computers have a positive influence on their teen’s writing, while teens are more likely to believe computers have no discernible effect.

- 27% of parents think the internet writing their teen does makes their teen child a better writer, and 27% think it makes the teen a poorer writer. Some 40% say it makes no difference.

On specific characteristics of the impact of tech-based writing, this is how parents’ and teens’ views match up:

For more details on parent and teens attitudes toward writing, please see Part 6: Parental Attitudes toward Writing and Technology on page 36 and Part 7: The Way Teens See Their Writing and What Would Improve It on page 42.

Teens enjoy non-school writing, and to a lesser extent, the writing they do for school.

Enjoyment of personal, non-school writing does not always translate into enjoyment of school-based writing. Fully 93% of those ages 12-17 say they have done some writing outside of school in the past year and more than a third of them write consistently and regularly. Half (49%) of all teens say they enjoy the writing they do outside of school “a great deal,” compared with just 17% who enjoy the writing they do for school with a similar intensity.

Teens who enjoy their school writing more are more likely to engage in creative writing at school compared to teens who report very little enjoyment of school writing (81% vs. 69%). In our focus groups, teens report being motivated to write by relevant, interesting, self-selected topics, and attention and feedback from engaged adults who challenged them.

For more details on teen enjoyment of writing and writing motivations, please see Part 8: What Teens Tell Us Encourages Them To Write starting on page 51.