Introduction

Americans deal with a broad array of problems in their lives, from health care to education to employment to retirement. Many of these are personal matters having little or no relationship to the government. Others are personal matters that require dealing directly with the government, such as obtaining a military pension, Social Security benefits or a driver’s license. Other matters, such as looking for a job or thinking of moving to a new city, could involve some contact with the federal, state or local government, if only as a provider of information and assistance .

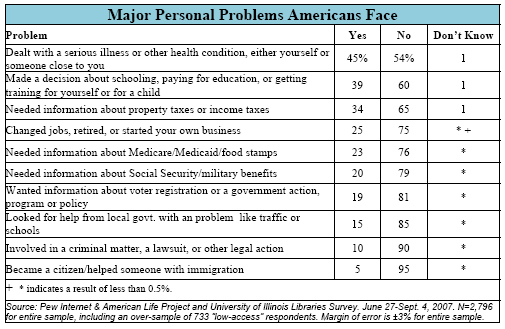

Here is the list of problems or questions and the percent of Americans who had dealt with each problem in the previous two years:

This survey asked questions about a variety of questions that would — or could — put people into contact with the government. Some matters required contact between government and citizens; some problems would provide an opportunity for contact; for still other matters, the government could simply be a source for helpful information.

The list of matters was designed to probe a range of information and assistance needs, although it is far from comprehensive. At one level, we wanted to see what kinds of matters had recently emerged in people’s lives. At another level, we wanted to see what information sources people turned to as they dealt with matters or confronted problems. And at yet a third level we wanted to see what role libraries might play as a resource for information, be they government documents or otherwise.

Demographic factors correlate with likelihood of experiencing some of these matters or problems. For example, 60% of parents say they have dealt with an educational matter, compared with 28% of those without a child under 18 at home. A total of 59% of Generation Y respondents (age 18-30 years) say they have dealt with an educational problem, compared with only 13% of the Matures (age 62-73 years).

Age is factor for the need to seek information about Social Security or military benefits. Just 20% of the younger cohorts said they had sought information on such benefits, compared with 27% of older Baby Boomers (age 52-61years) and 42% of Matures (age 62-71 years).

Americans report dealing with two or three of these matters in the last two years (a mean of 2.35 problems came in this sample). Other problems do not correlate with demographic factors.9

What search strategies do Americans use for problem solving?

Just as Americans face a variety of problems, they pursue a variety of means to seek information about those problems.

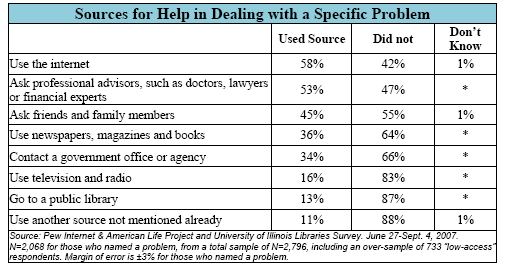

Instructing respondents to focus on one problem they had dealt with most recently, we asked them a series of questions, beginning with how and where they turned for information or help. Overall, nearly three in five adults (58%) say they used the internet for help; 53% say they sought out professional advisors, such as doctors, lawyers or financial experts; just under half (45%) turned to those closest to them, friends and family members, for advice and help; about a third of respondents say they looked to newspapers, magazines and books (36%) or directly contacted a government office or agency (34%); and about one in six looked to television or radio. Just about one in eight (13%) went to the public library.

Respondents would typically contact two or three sources for help. On average, each person sought help or information from just fewer than three sources (the mean equals 2.74 sources).

Some patterns emerge in how people seek information or solutions. Some of these patterns depend on demographic variables or other characteristics of the people who are seeking the information.

For example, younger respondents and those living in higher-income households were most likely to turn to the internet as a source for information or help. Fully 76% of the respondents in Gen Y (age 18-30 years) say they used the internet in dealing with their problem, compared with only 35% of the Matures (age 62-73 years). Seventy percent of those earning more than $40,000 a year used the internet, compared with only 46% of those at lower income levels.

Access to the internet also matters. Seventy-two percent of those with high-access to the internet say they turned to the internet for help, versus only 28% of those with low-access. Looking more narrowly at home access, connection speed mattered here as well. Some 77% of those with broadband internet access at home turned to the internet for help, compared with 57% of those with the slower dial-up access at home.

Since these matters are generally personal in nature, it should not be a surprise that most people (87%) reported using the internet at home, rather than at work or in a public venue, when they sought information or assistance with these matters.

Sometimes, patterns in how people seek information or solutions depend on the nature of the problem they are addressing.

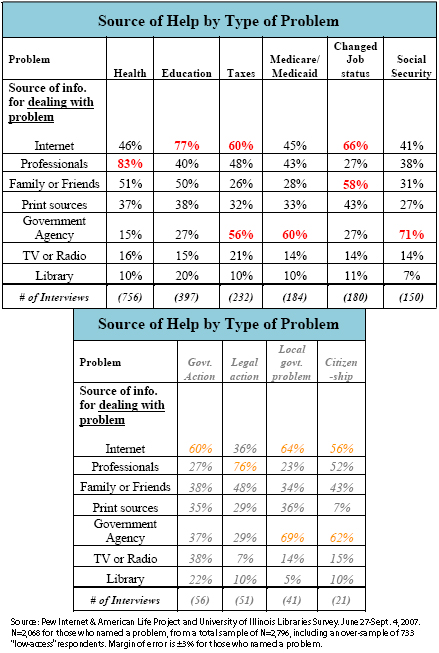

For example, needing specific information, like that about Social Security or military benefits, naturally suggests turning straight to the government agency or office that could supply that information. In this survey, 71% of people who sought help on Social Security or military benefits went to the appropriate government agency.

And finally, sometimes the nature of the problem means it will be relevant to certain cohorts in the population. For example, educational matters are more relevant to parents of children under 18 years old, or young adults who are still dealing with their own education. In this case, these cohorts are young and internet-friendly, which naturally drives the results toward “using the internet” as the preferred method for addressing matters related to education.

The table below reveals some interesting examples of how the nature of the problem bears on the method people choose for dealing with that problem: For example, 83% of those dealing with a health problem consulted with a health professional. Over half, 51%, talked with family and friends; 46% went to the internet looking for information or assistance; 37% consulted newspapers and magazines; all other sources were mentioned by fewer than one in five.

For assistance on educational matters, 77% of respondents identifying this problem used the internet to deal with it; 50% consulted family and friends; 40% consulted professionals; 38% used the print media; 27% contacted a government agency (not a surprise since most American children still attend publicly funded schools); and 20% went to the public library.

In dealing with property taxes or income taxes, 60% of those facing the problem say they went to the internet looking for help or assistance. That is roughly the same number as those who actually dealt with a government agency directly, 56%. Some 48% consulted the experts: professionals such as accountants, lawyers and tax advisers.

Those who were dealing with government programs such as Medicare, Medicaid and food stamps behave similarly to those needing information about Social Security and military benefits. In both cases, contacting the government agency topped both lists at 71% for Social Security and 60% for Medicare/Medicaid. The internet was second for both groups at 45% for Medicare/Medicaid and 41% for Social Security. Professionals were a close third for both groups.

In dealing with employment matters such as finding a job, retiring or starting a business, 66% of those facing the problem turned to the internet. Some 58% sought help from family and friends. This was the only problem where the print media, newspapers and magazines, played a major role: 43% of those dealing with employment matters used print media, despite the internet’s recent challenge to print as the traditional source of such information.

When Americans turn to the government for help with a specific problem

Just over one-third (34%) of respondents in this survey reported contacting the government – at some level – to look for information or assistance dealing with the specific problems included in this survey. (Overall, the number is much higher; when respondents are asked in a general way – not requiring them to think about a specific problem they dealt with recently. Some 58% of Americans say have contacted their government in the past year for some reason.)

When queried about the specific matters identified in this survey, respondents differed in their answers depending on their age. Specifically, 37% of those in the middle-age group, age 30-64 years, have sought help or information from the government, compared with 26% of those under age 30, and 27% of those age 65 and older. No other demographic variables were significant.

Specifically, how do Americans contact the government?

Calling a government office on the telephone is still the number one means that people report for seeking information or help (37%) with a specific problem. Reflecting the many options available today, using a combination of approaches – phone calls, visits, online actions or writing a letter – was the second most mentioned method, with 30% citing multiple methods of contact. Sixteen percent say they visited a government agency in person and 10% say they went to the agency website. Four percent say they sent an email and 1% say they sent a letter.

Education stands out as a factor potentially influencing how a person contacted a government office: only 18% of those with a high school education or less used multiple ways to contact the government versus 38% of those with at least a college degree. Income is also a major variable. Twenty-three percent of those with household incomes of under $40,000 say they visited a government office to seek help or get information, versus only 11% of those with higher incomes. Conversely, those in the lower income group were less likely to use a combination of communication channels (25%) compared with those making $40,000 and up (35%).

Access to the internet also seems to make an independent difference: 47% of those with low-access to the internet report calling a government office, while only 33% of those with a high-level of access to the internet report doing so. Conversely, only 21% of those with low-access report using a combination of means to contact the government, less than the 33% of those with high-access.

There are “non-internet users” who use the internet.

One of the lessons the Pew Internet Project has learned over the years is that those who say they are not internet users sometimes rely on others to go online for them. One in four non-internet users (27%) say they asked someone to use the internet to obtain assistance or information for them when dealing with one of the matters queried in this survey. This behavior does not seem to be identified with any demographic cohort, although the number of interviews in this group is relatively small and not conducive to making further conclusions. The data suggest that just one group does this frequently: parents who are not internet users themselves, but have children who are.