More than a buzzword, but still not easily defined

“Web 2.0” has become a catch-all buzzword that people use to describe a wide range of online activities and applications, some of which the Pew Internet & American Life Project has been tracking for years. As researchers, we instinctively reach for our spreadsheets to see if there is evidence to inform the hype about any online trend. What follows is a short history of the phrase, along with some data to help frame the discussion.

Let’s get a few things clear right off the bat: 1) Web 2.0 does not have anything to do with Internet2: 2) Web 2.0 is not a new and improved internet network operating on a separate backbone: and 3) It is OK if you’ve heard the term and nodded in recognition, without having the faintest idea of what it really means.

When the term emerged in 2004 (coined by Dale Dougherty and popularized by O’Reilly Media and MediaLive International),1 it provided a useful, if imperfect, conceptual umbrella under which analysts, marketers and other stakeholders in the tech field could huddle the new generation of internet applications and businesses that were emerging to form the “participatory Web” as we know it today: Think blogs, wikis, social networking, etc..

And while O’Reilly and others have smartly outlined some of the defining characteristics of Web 2.0 applications —utilizing collective intelligence, providing network-enabled interactive services, giving users control over their own data—these traits do not always map neatly on to the technologies held up as examples. Google, which demonstrates many Web 2.0 sensibilities, doesn’t exactly give users governing power over their own data–one couldn’t, for instance, erase search queries from Google’s servers. Users contribute content to many of Google’s applications, but they don’t fully control it.

Instead, the Web 2.0 concept was intended to function as a core “set of principles and practices” that applied to common threads and tendencies observed across many different technologies.2 However, after almost three years of increasingly heavy usage by techies and the press, and, as the writer Paul Boutin notes, after “Newsweek released the word, Kong-like, from its restraining quotes,” critics argue that the term is in danger of being rendered useless unless some boundaries are placed on it.3

Technology writers and analysts have, in fact, devoted countless hours to the meta-work of using Web 2.0 applications (blogs, wikis, podcasts, etc.) to debate and refine the definition of the term. Still, there has been little consensus about where 1.0 ends and 2.0 begins. For example, would usenet groups, which rely entirely on user-generated content, but are not necessarily accessed through a Web client, be considered 1.0 or 2.0?

In one sense, it doesn’t really matter that this bright line has been so elusive or that some savvy marketers simply use the label to distance themselves from the failures of Web 1.0 companies. That the term has enjoyed such a constant morphing of meaning and interpretation is, in many ways, the clearest sign of its usefulness. This is the nature of the conceptual beast in the digital age, and one of the most telling examples of what Web 2.0 applications do: They replace the authoritative heft of traditional institutions with the surging wisdom of crowds.

So what were those crowds doing online in the Web 1.0 era that was so different from what they’ve started to do over the past couple of years? Why bother with the new theoretical meta tag?

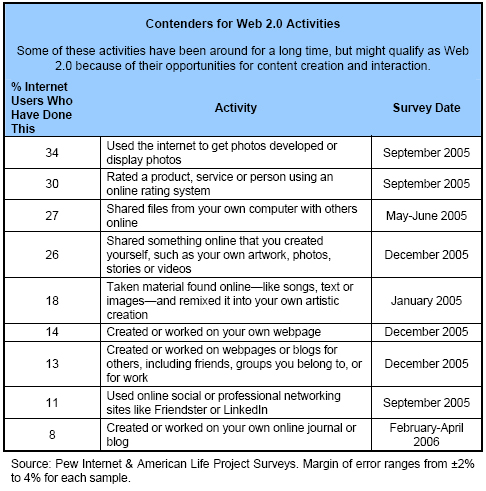

To be sure, there has been an explosion of businesses and applications that behave differently from the static Web of yore – Flickr, Wikipedia, digg, and Bit Torrent are just a small sampling among a growing wave of players and investment in this field. Data gathered by the Pew Internet & American Life Project over the past two years provides a rough user-centric portrait of online activities that demonstrate Web 2.0 characteristics:

Some activities under our Web 2.0 umbrella have been gaining in popularity. In 2001, 20% of internet users (or about 23 million American adults) used an online service to develop or display photos. By 2005, when the internet population had swelled to 145 million adults, 34% of internet users (or about 49 million American adults) had done so.

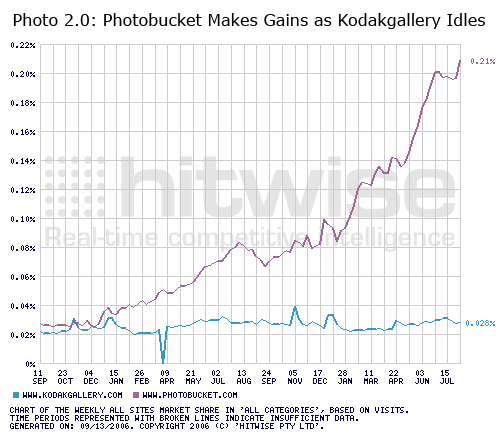

However, the applications used to upload, share and now tag photos have changed dramatically over the past year. Data gathered by Hitwise demonstrate the radical growth of a decidedly Web 2.0 socially-integrated photo service such as Photobucket diverging from the stagnant market share of a “traditional” online photo site like Kodakgallery.

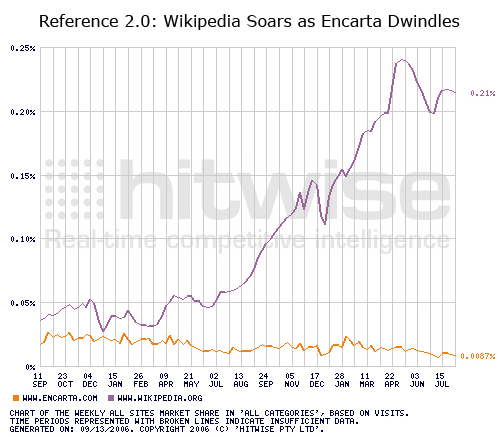

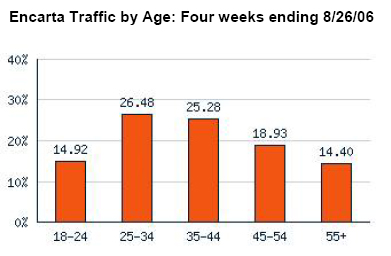

Even more dramatic is the past year’s traffic report for Wikipedia, one of the poster children for Web 2.0. The online encyclopedia whose content is shaped by the wisdom (and folly) of its users has launched into an upward trajectory that contrasts sharply with the sluggish growth of its corporate cousin, Encarta. In spite of, or perhaps because of the reputation speed bumps of the Encyclopedia Britannica and John Seigenthaler Sr. controversies during the past year, Wikipedia’s audience is now growing faster than ever. More users want to contribute to and edit entries, and more people are interested in reading them.

The Wikipedia entry on Web 2.0 is, of course, one of the richest sources of information on the term. MSN’s free online version of the Encarta Encyclopedia, in comparison, doesn’t yet have a Web 2.0 entry.4

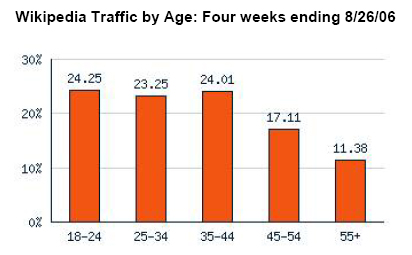

And while market share figures reveal part of the story, the demographic portraits disclose another important cog in the Web 2.0 machine: Like Soylent Green, these definitive5 applications, are, as blogger Ross Mayfield recently noted, “made of people.” But more than that, they’re made of young people.6

Despite all of this commotion over collaboration, participation and emancipation from static information, remnants of the linoleum-like Web 1.0 user experience still lie beneath the colorful rug of Web redux. Asynchronous email exchanges still top the charts of daily internet activities. We’ll say that again: Sending and reading email is still the most frequently reported internet activity by the average internet user, despite the growth in real-time communications like IM, text, and social network site messaging. Fully 53% of adult internet users sent or read email on a typical day in December 2005 – a figure virtually unchanged since 2000 when 52% of online adults emailed on a typical day. That’s more than instant messaging, blogging and online shopping—combined.

Even the omnipotent search engine can’t compete with email; only 38% of online adults use search on the average day. And while the volume of email messages with friends and family may be waning for those who have migrated their communications to social networking sites, those of us who wish to communicate with anyone over the age of 30 would be wise to keep an inbox up and running for the time being.

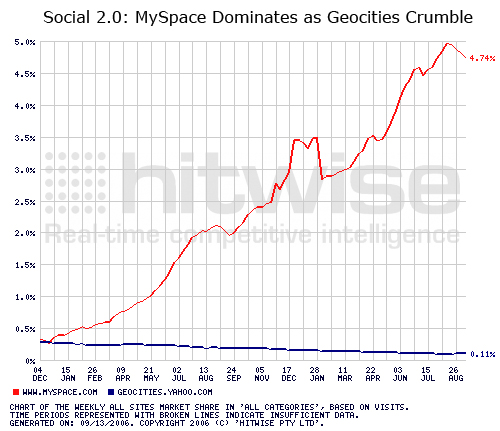

Whatever language we use to describe it, the beating heart of the internet has always been its ability to leverage our social connections. Social networking sites like MySpace, Facebook and Friendster struck a powerful social chord at the right time with the right technology, but the actions they enable are nothing new. A trip to the Geocities homepage on the “Wayback Machine” circa December 19, 1996 (courtesy of The Internet Archive) yields this decidedly quaint statement from the company: “We have more than 200,000 individuals sharing their thoughts and passions with the world, and creating the most diverse and unique content on the Web.”7 Replace “200,000” with “100 million” and you could almost imagine this sentence appearing on the MySpace homepage.

The Geocities vs. MySpace comparison not only demonstrates the commonalities between the internet of 1996 and 2006, but it also provides a point of departure for understanding concepts of online presence in the Web 2.0 era. While the Geocities model relied on the metaphors of a place (cities, neighborhoods, homepages), MySpace anchors presence through metaphors of a person (profiles, blogs, links to videos, etc.). Geocities encouraged us to create our own cities and neighborhoods as points of entry to our personal worlds; MySpace cuts to the chase and enables direct access to the person, as well as access to his or her social world. And whether we call the current world 2.0 or 10.0, there’s no question that the internet of today will look positively beta to future generations.