Introduction

Communication tools have long been at the heart of the popularity and utility of the internet for teens and adults. Email remains the most commonly reported activity among all groups of internet users. While many families initially acquire a computer and internet access for educational purposes, entertainment and communications functions generally eclipse school-focused online activities.

This section of the report charts the changes in the use of communications applications by teens over the past four years and places them in contrast to adult use of the same technology. As rapidly as the internet was adopted in the U.S., the defining characteristics of its use evolve at an even greater pace. Teen use of communications applications has undergone rapid changes in recent years. While statistically, the proportion of teens that have ever used email or instant messaging has remained stable, teen internet users report that they choose to use instant messaging more often than email and prefer it when talking with friends. Beyond tethered communications, teens are going mobile, using cellular phones for voice calls and text messaging. The landscape of communications options has changed radically since our last survey, and teens are often in the vanguard of adoption for these new technologies.

Email is still a fixture in teens’ lives, but IM is preferred.

For many years, email has been, hands down, the most popular application on the internet — a communications tool with a popularity and a “stickiness” that keeps users of all ages coming back frequently. But email is losing some of its appeal to these trend-setting young internet users as growing numbers express a preference for instant messaging. Almost half (46%) of online teens say they most often choose IM over email and text messaging for written conversations with friends. Only a third (33%) say they most often use email to write messages to friends, and about 15% prefer text messaging for written communication.

In all, 89% of online teens report ever using email. This represents no statistically significant change from when we last asked this question in 2000. However, responses to other questions in our survey and our qualitative research with middle-school- and high-school-aged teens suggest that the popularity of email and the intensity of its use are waning in favor of instant messaging.

More girls than boys use email, with 93% of all online girls reporting email use and 84% of boys saying the same. Much of the difference between boys and girls seems to be located in the email habits of online girls 15-17, of whom a whopping 97% report using email. Younger girls and older boys show similar use levels, with 89% of the younger (12-14) girls and 87% of the older (15-17) boys reporting email use. All of these groups report greater levels of use than younger boys, only 81% of whom say they use email.

Age alone is also a factor in email use. Independent of a teen’s sex, younger teens use email less. Particularly the 12-year-olds, and to a lesser extent, the 13-year-olds in our study are less likely to say that they have ever used email. Only 75% of 12-year-olds use email, while 87% of 13-year-olds are email users. Teens aged 14 and older are marginally more likely to say they use email, with 92% reporting use.

White teens are more likely than African-American teens to say they use email. Fully 90% of online white youth say they have ever used email, compared to 78% of African-American teens. Teens who have parents with higher levels of education are also more likely to use email, though a family’s household income is not a statistically significant factor influencing email use.

Teens who go online more frequently are more likely to use email. Of teens who go online on a daily basis, 95% report using email. Teens who go online several times a week are slightly less likely to report using email (88%) and those who use the internet less often than several times a week are significantly less likely to use email (68%).

Teens’ IM use still eclipses that of adults.

Teens’ love affair with instant messaging has continued full-throttle since 2000. Overall, three-quarters of online teens (75%) — and 65% of all teens — say they use instant messaging, almost the same percentage as the 74% of online teens who reported using IM in 2000. The overall number of teen IM users has grown as the population of online teens has grown. As of our current survey, about 16 million teens have used instant messaging now, up from close to 13 million in 2000.

Adults continue to lag far behind teens in adoption of instant messaging. Overall, only 42% of online adults reported using instant messaging in our most recent survey of adults.17

Just 64% of online African-American teens use instant messaging, which is a far lower percentage than the 78% of online whites who use IM. In comparison, Hispanics fall in between both groups at 71%. Overall, this means that 68% of all white teens use IM, 50% of all African-American teens use IM, and 63% of all English-speaking Hispanic teens use IM. Higher-income families, those earning more than $50,000 in annual household income were more likely to have kids who use instant messaging (80%) than lower-income households (69%).

Use of instant messaging varies according to age more than the sex of the teen. Older teens are more likely to use instant messaging than younger teens, with 84% of online teens aged 15-17 reporting IM use compared 65% of younger teens. As with email, the 12-year-olds are much less likely than all of the older teens 13-17 to use IM with only 45% reporting use. Among 13-year-olds, reported use jumps to 72% of all online teens that age. In contrast to the findings on age, boys and girls show little difference in their instant messaging use, with 74% of boys and 77% of girls using IM.

About half of instant-messaging teens use IM every single day.

Instant messaging has become a staple of teens’ daily lives. As more companies offer IM on phones, and more pocket-sized devices become available with keyboards and internet access, teens are starting to take textual communication with them into their busy and increasingly mobile lives. While the overall proportion of teens who use instant messaging has not changed significantly in the past four years, the intensity of teen’s use of the tool has increased.

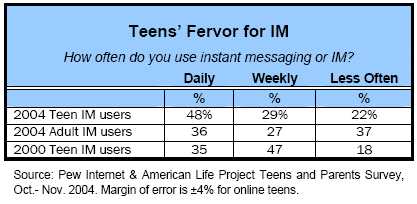

Almost half (48%) of those approximately 16 million teens who use instant messaging say they use it daily, with almost 30% of IM-using teens saying they use it several times a day, and another 18% saying they use it once a day. Another 18% of teens say they use the software/services three to five days a week, and 11% say they use it one to two days a week. Twenty-two percent of instant messaging using teens say they use it less often than once or twice a week.

In contrast to overall use of IM, the frequency of IM use varies more according to gender than age. Instant-messaging girls are somewhat more frequent users than boys. While 52% of all IM-using girls report instant messaging once or more per day, 45% of all IM-using boys report similar behavior. In comparison, younger and older instant-messaging teens communicate at about the same pace; 48% of those aged 12-14 say that they use IM once or more per day, while 49% of teens aged 15-17 say the same.

Teens in households with broadband access are more likely to report using instant messaging with 83% of broadband teens using IM versus 72% of teens with dial-up internet access. Unsurprisingly, broadband-using teens go online more frequently than dial-up users; 37% of broadband users say they use IM several times a day, compared to one quarter (24%) of dial-up users.

Teens’ current fervor for instant messaging surpasses the frequency with which teens used the technology when we last surveyed on the topic in 2000, and also exceeds adults’ current enthusiasm for the technology.

In December 2000, 35% of teens were using IM daily and 47% reported weekly use of the technology. Only 18% used it less often. In February 2004, 36% of adults who use instant messaging reported using IM daily, and 27% reported using it weekly. Thirty-seven percent said they used IM less often than weekly, with the largest chunk of those users using less often than every few weeks.

Teens’ enthusiasm for IM leads them to select it more frequently than other methods of written communication when talking with friends. When offered the choice among instant messaging, email and text messaging, teens are significantly more likely to choose instant messaging than email or text messaging. Fully 46% of teens said they choose instant messaging most often when communication by text with friends, compared with a third who choose email and 15% who most often use text messaging.

IM is especially pervasive in the lives of daily internet users.

Instant messaging activity varies according to how frequently a teen goes online. Similar to the findings with email, IM is a technology that uses “presence” or the ability to see others who are online at the same time to talk. And for those with less reliable or less frequent access or less time to talk, instant messaging may not be as useful a tool for communication.

Teens who go online daily are more likely than teens who go online less frequently to IM. Eighty-six percent of daily internet users use IM; 70% of teens who go online several times a week use IM; and less than half (48%) of those who go online less frequently use IM.

Teens are now clocking in longer hours on IM.

Teens are also using instant messaging for longer periods of time.18 On a typical day, the largest group of teens (37%) say they instant message for a half-hour to an hour. One-quarter (27%) say they IM for less than a half-hour a day, and another quarter (24%) say the IM for 1- 2 hours a day. A small but dedicated subgroup, (11%) IM for more than two hours on a typical day. Since 2000, there are more teens reporting lengthy average use times. In the past, 21% reported using IM for more than an hour on a typical day, compared to 35% of teens today. Not surprisingly, teens who use IM the most often, also report using it for the longest amounts of time.

The size of a teen’s buddy list varies with the intensity of IM use.

As mentioned above, one of the major features of instant messaging is something called “presence” — that is, the ability for the user to know who else is available on the network to talk at any given time. Teens know the makeup and size of their network through the buddy list.

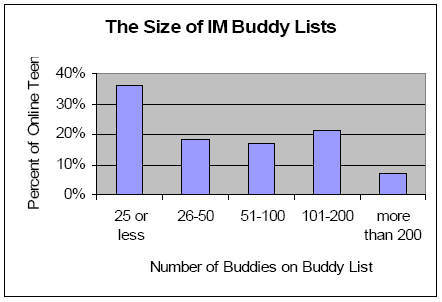

Buddy list size is directly related to the intensity and duration of IM use. Teens who use instant messaging more frequently, and/or for longer periods of time, report having larger buddy lists than young people who use the tool less often and in shorter sessions.

[people on buddy list]

A buddy list holds all of the screen names of conversation partners that a user has entered into his or her account, and shows which of those users are online and logged into the instant messaging program at any given time.

The largest group of teens, making up one-third of all teen instant message users (36%) say they have fewer than 25 buddies on their list. But 1 in 5 teens (21%), the next largest group, say that they have between 100 and 200 buddies on their list. Eighteen percent said they have between 25 and 50 buddies and 17% said they have between 50 and 100 screen names on their lists. Only 7% of IM-using teens say they have 200 or more buddies on their list.

Teens tend to IM with a core group of family and friends and stick to using one screen name.

Despite the large size of these IM buddy lists, most teens have a relatively small group of friends and family with whom they IM on a regular basis. Two in 5 teens (39%) report IMing with three to five other people on a regular basis. Almost a quarter, 24%, report IMing with 6 to 10 others, 20% IM with more than ten people regularly and 15% report one or two regular IM partners. Teens with larger numbers of regular conversation partners generally tend to log into IM more frequently (and for greater duration) than those who do not have as large IM networks.

Unsurprisingly, teens with larger IM networks spend longer periods of time instant messaging each day than teens with smaller networks. Close to six in ten of instant messaging users with one or two people with whom they IM on a regular basis say they IM for about a half-hour a day or less. Meanwhile only 8% of those with 11 or more regular buddies IM for a half-hour less per session. On the other end of the spectrum, only 7% of IM users with one or two regular buddies use the program for one to two hours per session, compared to more than a third (37%) of those with 11 or more regular IM buddies.

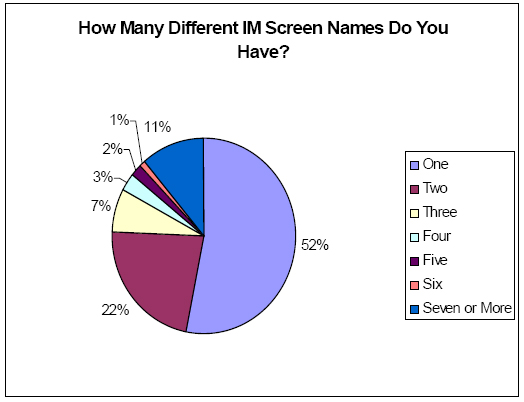

A majority of teens report using a single IM screen name. More than half (52%) of teens say they have one screen name for instant messaging, while another 22% say they have two. Thirteen percent of teens who use IM say they have three to six screen names and 11% of teens say they have seven or more IM screen names. Since most IM programs used by teens are free, it is possible to create an almost unlimited number of names.

Furthermore, many teens report having multiple screen names so that they can have more people on their buddy lists. Some of the most popular programs have a 200 buddy limit for lists. Some users also report creating additional screen names to get around being blocked by other users, as the blocker appears to be constantly offline to the blocked messager. By creating a new screen name, users can, under certain circumstances, ascertain if that person is online. Certain IM programs also allow users to link screen names together, enabling then to toggle back and forth between different online identities.

Many teens with multiple screen names report that they really only use one of the screen names. These screen names are often remnants of “earlier years” which the teen has not bothered to delete, names which now seem silly or juvenile to older teens, or screen names that were abandoned because of compromised passwords.

Teens who use IM more often are more likely to report having more than one screen name. The exception to this is for teens who use IM less often than every few weeks, who are slightly more likely than teens who go online a few times a week to have more than one screen name. These teens may have multiple screen names due to lost or forgotten passwords as a result of infrequent use.

IM offers ways for teens to express their identity and reshape technology to their purposes.

Some IM programs offer the option to post a profile that is visible to other IM users and may be made public to the world at large. More than half (56%) of all instant messaging users — or 36% of all teens — report they have created an IM profile and have posted it so that others can see it. In comparison, our survey of adults (18 and older) in early 2004 showed that just one-third (34%) of IM users had posted a profile.

Many teens have played with features of their software in ways that were probably not anticipated by designers. For instance, most IM programs allow users to post an “away” message when they are not sitting at a computer using IM. A large number of teens have started using the away message features to telegraph much more than just “I’m away.” By remaining logged into the system, IM users can receive messages from other users that will be waiting for them, like a sticky note on a desktop, when they return to their machine.

Eighty-six percent of instant messaging teens — or about 56% of all teens — have ever posted an away message, compared to 45% of instant message-using adults. Among teen IM users, almost two in five (39%) post an away message every day or almost every day. Among adults, that number drops to 18%.

Teens are not just using the standard options provided by their instant messaging programs; 55% of the approximately 14 million away message users say they do not generally post one of the standard away messages, instead they post their own. Among adults who use away messages, only a little more than a third (37%) report deviating from the standard software away message options. It should be noted that some IM programs, (like MSN) do not offer the option to customize away messages, instead giving users a list of approximately ten standard messages to choose from. Thus some users do not have the ability to post their own messages.

Sixty-two percent of the roughly 16 million IM-using teens have posted a specific away message about what they are doing or why they are away, and 28% have posted a phone number where they can be reached in an away message. Only 45% of adults have posted a specific away message and merely 12% have publicly posted a phone number where they can be reached.

Research by Naomi Baron at American University on the uses of away messages by college students outlined a number of purposes for away message use in this population. She found that in some cases, messages are simply conveying “I’m Away.” But in other instances, messages are intended to initiate contact with others, help plan a social event, send messages to particular other people, convey personal information about the message poster, or entertain those who might be reading them.19

[They’re posting]

Most IM teens have also chosen icons or avatars to represent themselves online.

Many instant messaging programs offer places to upload a graphic or photo to serve as a user’s icon or avatar.20 Sixty percent of teen IM users have posted a buddy icon that they associate with their user name. Icons can be anything from a photo of the user to an image of her favorite movie star, sports star, or cartoon character. Other times IM users may post short video loops or animations. Or teens may use something that they found online and thought was funny or amusing. Other teens report creating their own icon by drawing and scanning something or creating an image or a graphic through a graphic design program. And some instant messaging programs allow users to build cartoon avatars or virtual representations of themselves, or whatever else they’d like to be —including selecting gender, hair, eye and skin color, clothes, and a background or location.

Beyond selecting an icon or avatar, some instant messaging programs allow teens to customize how their instant messaging window appears to others by choosing a font, font color, window color, or even entire “skins” or design themes. “The color of the font and the background color is the important part for identifying just at a glance who you’re talking to…” explains one high school male.

A few focus group participants felt confined by the choices in instant messaging and resisted attempts to have their “personality defined by the computer and the service.” One young man said, “I’d rather be viewed and judged on the merit of my ideas expressed, as opposed to by what I put on there to look at or something.”

IM is the backbone of communication multi-tasking for teens.

Teens are using IM to converse with their friends. Notably, close to half of instant messaging teens (45%), say that when they use IM they engage in several separate IM conversations at the same time on a daily or almost daily basis. Contrast that finding with the fact that only 16% of adult IM users report similar behavior. Overall, only 4% of IM-using teens say they never engage in multiple simultaneous conversations over IM, compared with 38% of adults.

Much less frequently, instant messaging teens report setting up group conversations with their friends where everyone is in the same IM space at the same time. While 82% of IMing teens say they have ever set up a group chat, they do not do it very frequently. Those among the largest group of teens that instant message, 37%, report setting up group chats a few times a year or less. In contrast, only 38% of IM-using adults have ever set up a group conversation. Like their teen counterparts, adult IM users who hold group conversations over instant messaging only utilize this IM functionality infrequently, with the largest group of adult group IM chatters (20%) reporting using it less than every few months.

Teens are also using IM as a stealth mode of communication. Almost two in five (38%) of teens who instant message report IMing someone who is in the same location. This could be anything from IMing your mom as she works at another family computer upstairs at home or sending an IM to someone who is in the same classroom. Adults do this as well, but to a lesser degree. One-quarter of IM using adults report IMing someone who was in the same location.

Sending an instant message to someone in the same location is often used as a way to communicate with another person relatively privately. Rather than engaging in a spoken conversation that others could overhear, the only noise from an IM conversation is the sound of typing on a keyboard, allowing users to have some measure of privacy as they converse. However, the privacy of IM and other written modes of digital communication can easily be compromised. Many teens have had the experience of someone saving the text of an IM conversation and sharing it with others at a later time. Indeed, 21% of online teens say they have sent an email, instant or text message to someone that they meant to be private but which was forwarded on to others by the recipient. One-quarter (25%) of teens who go online daily have experienced this, compared with 16% of those who go online several times per week and 14% of those who go online less often.

In addition to being a tool that allows for quiet and relatively private conversation, instant messaging is also a nearly, but not completely synchronous place for exchange. While IM feels to its users like a conversation, there are still at least small, and sometimes large, lag times built into the system of exchange — including time lags because a user is conversing with someone else over IM to time associated with a user’s mental composition of a response and the time it takes to type it out on a keyboard.

Teens have long harnessed these small moments during IM conversations to enable them to accomplish other tasks while conversing. When teens go online, they will use IM as a “conversational” centerpiece while conducting other business in the time gaps. One female high school student said in a focus group:

“I usually check my email and I have an online journal and so I’ll write in that, chat with my other friends, and if I have little things to do around the house then I can do it [while instant messaging] because unless it’s somebody that responds quickly, then I can just go around and do something real quick and come back.”

Teens who have dial-up internet connections are also particularly fond of multi-tasking, as it takes advantage of the long waits for downloading large files to send instant messages or accomplish other tasks.

“I do more than one thing at once [while online] because my connection is so slow. If I dedicated my attention to one webpage, I’d go crazy waiting for it to load every time.”

— High School Male

Teens use IM to stay in touch with far-away friends.

Teens say that instant messaging is a vital tool in helping them manage their increasingly complex schedules. Almost all of the 16 million teens who use instant messaging (90%) said they use IM to keep in touch with friends who don’t live nearby or who do not go their school. This proportion is unchanged from when we asked the same question of IM using teens in December of 2000.

IM is also a popular way for teens manage the demands of daily life.

Teens use instant messaging to make social plans with friends — 80% of IM using teens report they employ IM to make plans.

IM is also a place to start, establish and end romantic relationships. Teens use IM to conduct sensitive conversations around romantic subjects, as well as other types of discussions that they may not have the courage to broach face-to-face. One in five teens (20%) said they had asked someone out over IM and a similar number (19%) said they had broken up with someone with an instant message. These proportions have remained relatively stable since we last asked the questions in December of 2000. At that time, 17% of teens had asked someone out on IM and 13% had broken up with someone. Teens report that instant messaging makes these awkward conversations easier, since the mediated nature of the communication protects the instigator from having to see the body language or even hear the tone of voice of the other person in the conversation.

IM is not just a way to establish and maintain relationships but is also a venue for discussing school work. Nearly eight in ten (78%) instant messagers said they talked about homework, tests, or school work over instant messaging.

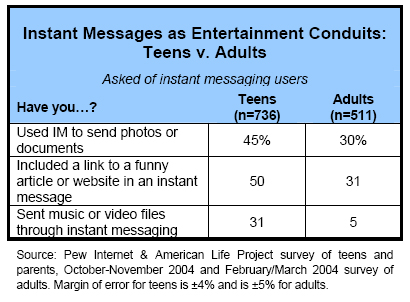

Instant messaging is also a conduit for information outside of the conversation taking place. Teens use IM to send files, images, photos, documents and links to other online material.

Next-generation IM is also starting to take hold. Some IM programs now make it possible to use audio or video streaming, sometimes in combination with typed conversation. While not widespread or necessarily enabled in all instant messaging programs, more than one in five teens (22%) have used streaming audio or video to hear or see the people they instant message. This compares to just 14% of adults who have done this.

Instant messaging has such wide-ranging functionality that for some teens their usernames or screen names have replaced their phone numbers as a preferred way to establish contact with others. Focus group participants reported that they no longer give out their phone number, but instead give potential new friends and romantic partners their screen name. Said one high school male: “People will give me their screen name…before they’ll give you a phone number.”

In many cases IM allows teens to remain in touch with or talk to people that they wouldn’t talk to in other ways.

“It’s a good way to talk to people that you couldn’t usually call or that live far away…or people that you don’t know well enough. It’s a good way to get to know people.”

– High School Male

IM is also a good way to efficiently maintain relationships with friends. One high school female in our focus group explained:

“If you only have like an hour and a half to spend on the internet then you could talk to like maybe ten people. Whereas you can only talk to three people if you were going to call.”

Most teens will block messages from those they want to shun or avoid.

Communication via instant messaging is not always a positive exchange of pleasantries and conversation. Many instant-message-using teens report blocking someone from communicating with them through IM. In all, 82% of the roughly 16 million IM using teens have ever blocked someone, compared to 47% of IM-using adults who report engaging in this behavior. Generally teens and adults do not need to do this very often, with more than half (52%) of teens reporting blocking someone less than every few months, and 26% of adult instant messagers reporting the same. In our previous study of teens, we found that 57% of online teens said that they had ever blocked an instant message from someone they did not wish to hear from. These questions cannot be directly compared due to different question wording; nevertheless, the similarity of the question and difference in the responses suggests that blocking behavior has increased.

Away messages can also be used to dodge conversation partners. Focus group teens describe setting up an away message that remains up even when the user has returned to the screen. One young woman told us:

“I have a version where I can have my away message up, but I can still talk to people and my away message won’t go down. So if I don’t want to talk to somebody, then I just put up [that] away message and talk to the people that I want to and the other people I can avoid.”

Said another teen girl:

“Some times I just get tired of being online. I’ll put my [away] message up and then don’t come back for a day or so.”

IM pranks are increasingly common among teens.

Teens also love to play practical jokes with instant messaging. Almost two in five (39%) of teens have ever played a trick on someone online by pretending to be someone else over IM. Sometimes teens have hijacked an instant messaging program that someone else failed to log out of on a shared computer. Other times they may have discovered or were told someone else’s password, allowing them to login under their screen name. One member of a high school focus group explained how some pranksters get access to the passwords of others:

“Sometimes if you go to someone else’s house, it might save automatically [when you use IM on their computer]. Your password might save onto their computer. You can uncheck the box [on the IM program] and it won’t save, but most people just don’t bother with that.”

And in some cases, teens make up new screen names and then IM their peers pretending to be someone else. This joking behavior has increased since we first asked, up from 26% in late 2000, an 88% increase over four years in the proportion of IM users who are IM mischief-makers.

One young woman caught a prankster in the act:

“I was on IM under a different screen name, and then I saw myself sign on, and I was like, hmmmm….I was just really confused. I started talking to them, and I’m like ‘Who is this?’ I’m like ‘Why are you on my screen name?’ But I just found out it was my neighbor, so I didn’t really care. I got a new screen name. So they can’t—and I know they wouldn’t—do anything bad with it. I didn’t really worry about it.”—High School female

As mentioned above, teens have also noticed the dis-inhibiting effects of computer-mediated communication. Close to a third of teens (31%) report having written something over instant messaging that they wouldn’t say to someone’s face. This is a slight decline from the proportion of IM users who reported this when we first asked the question in 2000. At that time 37% of IMing teens reported writing things online they would not say to someone’s face. Of course, the things that are said over IM that wouldn’t be said face-to-face could be of both a positive and negative nature. Sometimes these statements or comments can be hurtful, but other times they can be positive. IM often allows teens and adults to say things that might otherwise cause embarrassment, or to have a discussion that clears the air after a conflict, conversations that might be harder to have in a face-to-face manner.

Nearly half of teens have cell phones.

Close to half of all teens (45%) own their own cell phone. A similar proportion of internet users (47%) report cell phone ownership. Girls are more likely than boys to own a cell phone, with half of girls (49%) and a little more than two in five boys (40%) saying they have a mobile phone.

Younger teens are much less likely to have phones than older teens — less than a third (32%) of teens aged 12-14 have a cell phone, compared to more than half (57%) of older teens aged 15-17. When we break it down by grade, we see a big jump in cell phone ownership when teens enter middle school. A little more than one in ten (11%) 6th graders has a cell phone, compared to a quarter (25%) of 7th graders. The next jump comes when teens go to high school. Under a third (29%) of 8th graders have a phone, but nearly half (48%) of 9th graders do. The last big jump comes among high school juniors and seniors, of whom two-thirds (66%) have cell phones.

Urban teens are the most likely of all teens to have a cell phone. More than half (51%) of urban teens own a cell phone, followed closely by suburban with 46% reporting cell phones and trailed by rural teens, of whom only a little more than a third (35%) report owning a cell phone. Of course, given that cell phone coverage is best in the most densely populated parts of the country, it makes sense that a cell phone may be less useful in rural and far outer suburban areas than in center cities.

Teens with broadband home internet access are somewhat more likely to have a cell phone than dial-up users. Nearly 43% of dial-up users have a cell phone, compared to half (51%) of home broadband users. Broadband access is intimately tied to other economic factors, and thus families able to invest in broadband access at home are more likely to have disposable income to pay for cell phones for teens.

Cell-phone-owning internet users are more likely than others to engage in other online communication activities. More cell phone users report having ever sent instant messages than other internet users, and they are more likely to have ever sent a text message and use email. Nearly 86% of cell phone users use instant messaging, compared to only 65% of teens who do not have a cell phone. Sixty-four percent of cell phone owners send text messages, compared to 15% of those without cell phones. Cell phone owners are slightly more likely to use email that those without a phone — 93% of cell phones send and receive email messages versus 85% of the cell-phone-less. Notably, 7% of teen cell phone owners say they do not go online. However, even though cell phone owners are more likely to have ever done these activities, they are not necessarily more likely to choose to use these tools most often when communicating with peers.

Cell phone text messaging emerges as a formidable force. Older girls are the most enthusiastic users.

American teens have begun to embrace text messaging. While they still lag behind many of their European and Asian counterparts, one-third (33%) of all American teens report sending text messages using a cell phone, and 64% of teens who own a cell phone say that they have sent a text message.

Text Messaging, also called texting or short message service (SMS), is a service that allows a user to send a message of no more than 160 characters from a cell phone or a computer to a cell phone user. Text messages may also be sent from cell phones to email addresses, instant messaging programs, and landline telephones.21

Text messages are generally sent using the keypad on a cellular phone, with each number on the pad standing in for three or four letters of the alphabet. The user addresses the message to a phone number or address, types in the words using the keypad, and then hits send. The recipient, if their phone is on and able to receive texts, will receive notification of the receipt of the message, often accompanied by a tone or sound.

Older girls are the most enthusiastic users of text messaging.

Older girls have embraced cell phone-based text messaging, with 57% of online girls aged 15-17 having sent or received them. Older boys are the next most enthusiastic group, with 40% of online boys reporting using text messaging. Among younger teens aged 12-14, 30% of online girls and 24% of online boys have ever sent texts. Use of text messaging in this group may be suppressed due to lower levels of cell phone ownership among younger teens — 32% of teens aged 12-14 own a cell phone, while 57% of teens aged 15-17 do. Girls are also slightly more likely than boys (49% vs. 40%) to own a cell phone.

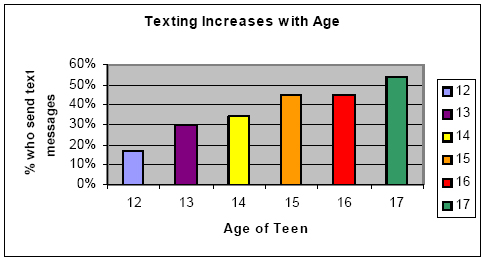

Overall, 45% of online girls have sent a text message, compared to one-third of all online boys (33%). We see a similar break between younger and older teens. Almost half (48%) of teens aged 15-17 have sent text messages, versus only 27% of teens aged 12-14. When we look at the individual age or grade level, teens show a steady increase in reported text message use as they grow older, from 17% of 12-year-olds reporting text messaging, to 34% of 14-year-olds, 45% of 15-year-olds, and 54% of 17-year-olds sending texts. There is no significant difference among racial and ethnic groups, household income, or parent education levels when it comes to text messaging on a cell phone.

Daily internet users are more likely to use text messaging.

Daily use of the internet is associated with a greater likelihood of use of text messaging on a cell phone. About 44% of all teens who go online daily send text messages, as do a little more than a third (36%) of those who go online several times a week. About a quarter of teens who go online less often send text messages.

Text messaging’s appeal lies in both its mobile nature and its similarities to instant messaging. Text messaging allows the user to send short messages quickly and privately to a specific individual. A high-school-aged girl in our focus group told of sending text messages in school, describing it as “the same as passing notes.” Other teens told of the utility of being able to send a message to a cell phone “that doesn’t have to be answered, like a phone call” but rather can be accessed and read by the recipient at a convenient time.

Still, there are some who have tried text messaging and have found it frustrating. One teen told us that “it takes too long, depending on what you have to say” and another chimed in:

“I think text messaging is still too new. It’s too expensive and it doesn’t come with enough programs. And it’s not compatible enough between different kinds of cell phones and stuff for it to work as well as instant messaging yet. Maybe it will be someday, but right now, it’s not worth it.”

— High School female