Wired Americans hear more points of view about candidates and key issues than other citizens. They are not using the internet to screen out ideas with which they disagree.

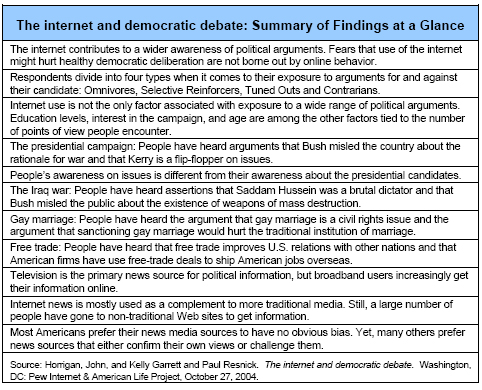

The internet contributes to a wider awareness of political arguments. Fears that use of the internet might hurt healthy democratic deliberation are not borne out by online behavior.

Increasing numbers of Americans are getting news and information about politics online. More than 40% of those who use the internet have gotten political material during this campaign, according to the Pew Research Center for The People & The Press, more than 50% higher than the number who had gotten such information in the 2000 campaign.

As internet use has grown, prominent commentators and scholars have expressed concern that this would be harmful to democratic deliberation. They worried that citizens would use the internet to seek information that reinforced their political preferences and avoid material that challenged their views. They feared that people would use internet tools to customize and insulate their information inputs to a degree that held troubling implications for American society. Democracy functions best when people consider a range of arguments, including those that challenge their viewpoint. If people screened out information that disputed their beliefs, then the chances for meaningful discourse on great issues would be stunted and civic polarization would grow.

The Pew Internet & American Life Project and the University of Michigan School of Information conducted a survey in June to to test those concerns. We focused on the role of the internet related to four dimensions of contemporary politics: the arguments anchoring the campaign between George W. Bush and John Kerry; the arguments for and against the war in Iraq; the arguments for and against gay marriage; and the arguments for and against free trade. And our survey results belie the greatest fears about the impact of the internet on democracy:

The internet is contributing to a wider awareness of political views during this year’s campaign season.

At a time when political deliberation seems extremely partisan and when people may be tempted to ignore arguments at odds with their views, internet users are not insulating themselves in information echo chambers. Instead, they are exposed to more political arguments than non-users.

While all people like to see arguments that support their beliefs, internet users are not limiting their information exposure to views that buttress their opinions. Instead, wired Americans are more aware than non-internet users of all kinds of arguments, even those that challenge their preferred candidates and issue positions.

Some of the increase in overall exposure merely reflects a higher level of interest in politics among internet users. However, even when we compare Americans who are similar in interest in politics and similar in demographic characteristics such as age and education, our main findings still hold. Internet users have greater overall exposure to political arguments and they also hear more challenging arguments.

What do people know about politics and how they come to know it?

A primary objective of this research was to find out whether the internet is reducing the number of points of view that people hear about politics and public affairs, particularly arguments that are at odds with respondents’ beliefs. Such a research undertaking has to be grounded in the context of people’s overall media use, interest in politics, and other attitudinal and demographic factors. It is not sufficient, therefore, to ask people a question like this: “Do you use the internet to shield yourself against arguments that are at odds with your existing point of view?” Some people may do this, but they would not want to admit it, because most people like to say they are open-minded. Answers to these kinds of questions would not be trustworthy.

To avoid this pitfall, our survey was designed to examine the kinds of arguments people have heard about politicians and issues and to learn what communications and media channels they may use to gather such knowledge. For the presidential race, respondents were asked about their candidate preferences, and were read eight statements about the two major candidates; four statements were favorable to Bush and four were favorable to Kerry. In addition to inquiring about respondents’ internet use, the survey also asked about people’s media use, overall interest in the campaign, and open-mindedness. This allowed us to evaluate a more subtle question:

- Is online Americans’ use of the internet tied to their awareness of arguments for or against the politicians and issues they support, or do other factors besides internet use explain their awareness?

This approach is more reliable than just counting up the number of arguments people have heard about candidates and observing that internet users have heard more of them. That happens to be true. Yet it could be true not because people use the internet, but because internet users are more interested than others in politics, or because they have higher levels of education than others.

The real impact of internet use comes when statistical techniques are used to assess what portion of that truth can actually be tied to the internet, as opposed to other factors.

This further analysis shows that internet use predicts that people will have greater exposure to arguments that challenge their views.

These internet effects are independent of other things that also predict exposure to political information, such as advancing age, use of traditional media, or interest in the campaign.

Internet use is not the only factor associated with exposure to a wide range of political arguments. Education levels, interest in the campaign, and age are among the other factors tied to the number of points of view people encounter.

There are several traits that are associated with relatively broad exposure to arguments about the candidates and the issues we studied. The strongest predictors of the breadth of arguments heard about the candidates are interest in the campaign and advancing age. As for media use, the internet expands people’s informational horizons about the candidates, as does daily attention to TV news and the newspaper.

People’s degree of open-mindedness and their overall interest in the campaign are the largest factors relating to their exposure to challenging arguments.

Though these factors also shaped issue exposure, there were a few interesting variations. For example, men knew less about gay marriage and more about free trade than women did on average. The importance of community type also varied across issues. People living in rural areas typically knew more about gay marriage, but were no different than those living in urban or suburban communities with regard to their exposure to the Iraq conflict or free trade.

The presidential campaign: People have heard arguments that Bush misled the country about the rationale for war and that Kerry is a flip-flopper on issues.

At the time of this survey, 44% of respondents favored President Bush and 39% supported Senator Kerry. Here were some of the notable findings

- As of early July, 42% of internet users had gotten news about the campaign online or through email. That represents more than 53 million people.

- Of all the arguments being made in the campaign the most well-known about Bush was that he misled the public about the reasons for going to war with Iraq (94% of Americans had heard that argument) and the most well-known about Kerry was he changes positions on issues when he thinks it will help him win an election (70% had heard that argument).

- Those who are partisans of either candidate are more likely to have heard many arguments about the race – both pro and con – than those who do not yet strongly support either candidate. The partisans are clearly paying attention to all the back-and-forth of the campaign.

Respondents divide into four types when it comes to their exposure to arguments for and against their candidate.

Of the eight arguments people were presented about Bush and Kerry, the respondents said they had heard, either frequently or sometimes, an average of 5.2 of them. Internet use had a positive effect on the number of arguments they had heard. However, not all respondents are equally enthusiastic about finding out the arguments for or against the candidates.

- Omnivores have heard many of the arguments pertaining to both candidates. They make up 43% of those with a position on the two candidates. Generally, Omnivores are very interested in the political campaign and they are the most ardent news consumers among the four groups. They get news from many sources, including TV, newspapers, and the internet. Omnivores have heard many of the arguments pertaining to both candidates.

- Selective Reinforcers know a lot about the arguments in favor of their candidate, but relatively few about the opposing candidate. They make up 29% of those with positions on the candidates. They are about average in terms of their interest in the campaign, media consumption, and internet use. Two-thirds of Selective Reinforcers are Bush supporters, one-third support Kerry for president.

- Tuned Outs have heard relatively few arguments about either candidate. They represent 21% of the population with stated preferences on a candidate. Those in this group do not express great interest in the campaign, and are not news hounds from any media source. And they are less likely than the general population to go online or have college degrees.

- Contrarians know a good deal about the arguments in favor of the candidate they oppose, and relatively little about their guy. Some 8% of respondents who have a position on the candidates fall into this group. Their interest in the campaign is a little lower than average and their use of traditional media and the internet is at about the national average.

People’s awareness on issues is different from their awareness about the presidential candidates.

On the three issues we probed, it was surprising to note that, in general, people had heard more about the issues than the candidates. This may be because we only asked people about issues that they said were important to them, while we asked every respondent about the campaign. Furthermore, in contrast to campaign exposure, in which respondents were equally likely to have heard arguments favoring Bush or Kerry, issue exposure was less balanced. People had generally heard more arguments favoring one position or another. For instance, respondents had heard more arguments for the Iraq war than against it, and more arguments against legalizing gay marriage than for it.

The evidence of selectivity in issue exposure is less consistent than with campaign exposure. Still, there is no indication in this survey that people are using the internet to avoid assertions that confront their views.

The Iraq war: People have heard assertions that Saddam Hussein was a brutal dictator and that Bush misled the public about the existence of weapons of mass destruction.

Some 53% of the respondents in this portion of the survey said they thought the decision to go to war was right and 39% thought it was wrong.

- As of early July, 53% of internet users had gotten news about the Iraq war online or through email. That represents over 67 million people.

- Compared to the other issues we explored, people had heard more of the arguments for and against the use of military force against Iraq. A typical respondent heard at least occasionally 7.1 out of 8 arguments we queried.

- Of all the arguments being made in favor of the war, the most well-known was that Saddam Hussein was a brutal dictator who murdered and tortured his own people (98% of Americans had heard that). The most well-known anti-war argument was that the Bush administration had misled Americans about Iraq having weapons of mass destruction (87% had heard that argument).

Gay marriage: People have heard the argument that gay couples should have the same legal rights as heterosexuals when it comes to economic benefits and the argument that sanctioning gay marriage would hurt the “sacred religious institution” of marriage.

In this portion of the survey, 70% of respondents said they opposed gay marriage and 26% supported it.

- As of early July, 35% of internet users had gotten news about gay marriage online or through email. That represents over 44 million people.

- People were more likely to have frequent exposure to the arguments against legalizing gay marriage than for it. On average, respondents heard 2.3 arguments challenging legalization frequently, versus only 1.9 arguments supporting it frequently.

- Of all the arguments being made in favor of gay marriage the most well-known was that gay couples are entitled to the same legal rights as heterosexual couples when it comes to things like health insurance and inheritance (85% of Americans had heard that). The most well-known argument against gay marriage was that marriage is a sacred religious institution that should be between a man and a woman (97% had heard that argument).

Free trade: People have heard that free trade improves U.S. relations with other nations and that American firms have used free-trade deals to ship American jobs overseas.

Some 31% of those queried in this portion of the survey believe that free trade has been mostly good for the U.S. economy and American workers, while 41% believe free trade has been mostly bad for the economy and workers.

- As of early July, 26% of internet users had gotten news about the debate over free trade online or through email. That represents over 33 million people.

- Of all the arguments being made in favor of free trade, the most well-known was that free trade improves U.S. relationships with other countries (77% of Americans had heard that). The most well-known anti-free trade argument was that it allows companies to lay off American workers and send their jobs overseas (89% had heard that argument).

Television is the primary news source for political information, but broadband users increasingly get their information online.

Three-quarters of all Americans (78%) say television is a main source of campaign news. Some 38% of Americans say newspapers are a primary source; 16% say radio; 15% say the internet; and 4% say magazines. (These figures don’t add up to 100% because respondents were allowed to give up to two answers.) In addition:

- 83% of respondents say TV is where they get most of their information about the war in Iraq.

- 69% of respondents say TV is where they get most of their information about the issue of gay marriage.

- 59% of respondents say TV is where they get most of their information about the issue of free trade.

- 31% of Americans with high-speed connections at home identify the internet as a main source of campaign news. This rivals the share of broadband users who say newspapers are a main source (35% do) and far exceeds the 15% who identify the radio as a main source of campaign news.

Internet news is mostly used as a complement to more traditional media. Still, a large number of people have gone to non-traditional Web sites to get information.

People are not abandoning traditional news media for the internet.

- Of those who get news online on an average day, 90% also got news from a newspaper or TV.

- Of those who ever get news online, 99% also get news from a newspaper or TV.

The Web sites of major media organizations continue to dominate as sources of online news about politics and public affairs. But political news sites not associated with a major news organization are beginning to get a foothold for internet users, particularly those with broadband at home.

Some 24% of home broadband users are going to alternative online sources. Some 24% have visited the web site of an international news organization, and 16% say they have visited a more partisan alternative news organization’s site. Use of these alternative sources is almost always accompanied by use of other more mainstream sources. Nearly 100% of the users going to the alternative sites we asked about also use some other mainstream source. Again, this supports the idea that internet users, especially those with high-speed connections, are not organizing their searches to avoid arguments that would conflict with their views.

- 59% of all internet users have gotten news from a major news organization, with nearly three-quarters of broadband users having done so.

- 18% of internet users have gone to the Web site of an international news organization such as BBC or al Jazeera; one-quarter of home broadband users have done this.

- 11% of internet users have gone to alternative news sites such as AlterNet.org or NewsMax.com; one in six home broadband users have done this.

- 10% of internet users have gone to Web sites of liberal groups such as MoveOn.org, with 15% of broadband users having done this.

- 10% of internet users have gone to Web sites of conservative organizations such as the Christian Coalition. Some 10% of broadband users have done this.

Taken together, 30% of all internet users have been to at least one of the four latter non-mainstream media sites. Notably, supporters of John Kerry are more drawn to non-mainstream sites than Bush supporters:

- 36% of Kerry supporters have been to a non-mainstream media site for political news.

- 29% of Bush supporters have been to a non-mainstream media site for political news.

Most Americans prefer their news media sources to have no obvious bias. Yet, many others prefer news sources that either confirm their own views or challenge them. Surprisingly, almost as many prefer news that challenges their views.

Most Americans prefer their news straight, without an obvious point of view. However, about one-quarter of respondents say they like to get news from sources which conform to their political outlooks.

One of the surprises in the survey is the finding that a fifth of Americans (18%) say they prefer media sources that are biased and challenge their views, rather than reinforce them.