Politics is local. The Internet is global. Where do the two meet?

The last three years have provided powerful evidence of how the Internet and email have entered national and international political life. Activists used it mobilize interested citizens and to handle the logistics of organizing such mass demonstrations as the 1999 protests at the World Trade Organization talks in Seattle and the Million Mom March in Washington, DC. Conservative activists can also find online rallying points at such sites as http://www.nra.org/ and http://www.townhall.com/.

Moreover, there has been strong growth in the number of online Americans who use government Web sites. In our latest survey on the subject in July 2002, we found that 62% of U.S. Internet users – some 70 million people – have used government agency Web sites, up from 42 million who had used agency Web sites when we first started probing on the subject in March 2000. On a typical day in July, more than 9 million people were going to Web to get information and services from public agencies.

But while the Internet allows people to access Web sites and activists to communicate effectively with each other, it has not proven to be as important a tool for communicating with some kinds of policymakers. The ease with which those promoting a cause can solicit thousands – or even tens of thousands – of emails to be sent to any number of politicians has lead to a backlash against email campaigns on Capitol Hill. The Congress Online Project reported that that House of Representatives received 85.5 million email messages in 20011 (an average of almost 540 messages per day to each office). Activists now warn about the futility of sending multiple copies of identical emails to overburdened congressional staff, so popular have email campaigns become among citizens.2

Could the Internet create the same dynamic in local government affairs? Can community leaders tap into the same passions and online organization that other activists have done to launch national campaigns? Will local leaders take to online engagements with their constituents?

At first glance, it would appear that local government provides a very different environment for online relations than does the national government. Only half of Internet users know if their local government has a Web site, even though about 80% of cities do.3 While two-thirds of Internet users say the Net helps them get involved with groups outside of their communities, only 9% say it’s useful for things close to home. Just 1 in 9 users are aware of a debate in their community where the Internet played a major role in organizing citizens to communicate with public officials.4

Anecdotal evidence from the ongoing “Query of the Moment” survey maintained on our Web site supports the idea that people rely only marginally on the Internet for local needs. Responses to the question “Do you often go to the Web sites of local institutions?” ranged largely from surprised (“Why check local content on the Web?”) to disillusioned. Many respondents noted the lack of interesting local content on Web sites. Several noted that they relied heavily on locally-oriented Web sites to get their bearings when they moved to a new town, but few indicated that their ongoing local lives are significantly enriched by the Internet.

Even so, a few news stories have noted the prominence of online networks in urban life. In the early 1990s, the Public Electronic Network in Santa Monica allowed homeless participants to participate in a community campaign for better access to lockers and showers.5 And in 2000, The Preservation Resource Center in New Orleans successfully activated email lists to save a historic building from demolition.6 In that case, fewer than 100 emails seemed to have a profound effect on state legislators.

The proximity of online local officials to their constituents provides a communications paradox. On the one hand, local officials live and work in the communities they serve, their loyalties and interests generally undistracted by partisan issues or issues that affect populations beyond their specific electorate. They should be very approachable. On the other hand, many work without staff or even office space, so may not always be easy to reach. The Internet and email could allow citizens and officials to connect where traditional means fall short.

We surveyed local elected officials across the country to get an understanding of their experiences in dealing with the electorate online. Our research shows that city governments are now eager to have a presence online, and that city officials appreciate the benefits of electronic communications. However, they are also aware of the shortcomings of clumsy handling of this new media.

Methodology and respondents

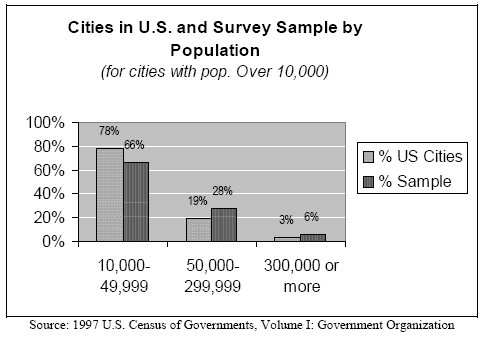

A random sample of 2,000 local elected official was drawn from the National League of Cities database of municipal officials. Officials were selected from cities with populations greater than 10,000. The survey was mailed out to all officials during January 2002. Officials were given the choice of responding on the mailed survey or taking the survey online at a password-protected site. Non-respondents received a follow-up postcard and then a second letter. The survey closed on April 30, 2002.

We received responses from officials in 520 cities, with populations ranging from just under 10,000 to 3.5 million. Of the respondents, 23% are mayors, 71% sit on the city council or the local equivalent legislature, and 6% describe themselves as “other.”

The response rate was slightly over 25%. Not all officials answered all questions.

The respondents fairly closely mirror the composition of the universe of municipal officials throughout the United States. The population breakdown of the cities represented by respondents roughly mirrors that of municipal governments across the nation, although our sample was somewhat more weighted towards more populous cities. Mayors who responded tended to come from smaller cities. The average population of a city for which the mayor responded was about 45,000, compared to 91,000 for the cities of responding council members. Thus, the sample is not a fully representative one. However, officials at the National League of Cities and we believe it is a very good accounting of the range of experience and beliefs among municipal officials.