Key findings

By Steven M. Schneider

SUNY Institute of Technology, College of Arts and Sciences

Kirsten A. Foot

University of Washington, Department of Communication

Co-Directors, WebArchivist.org

A “Webscape” of examples for this section can be found at:

http://september11.archive.org/webscape/sch/

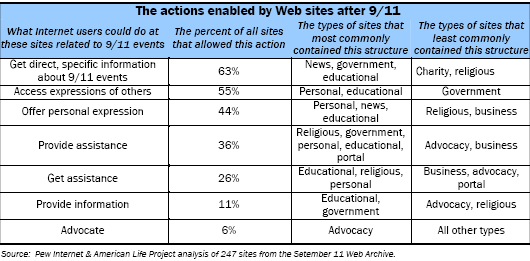

The rapid development of new content and features on the Web affected how many Americans responded to the September 11 attacks by providing structures through which they could obtain and provide information and assistance, share their reactions, and convey their policy preferences to governmental bodies.

The creation of online structures facilitated both online and offline actions by Web users. Of 247 Web sites produced by a variety of organizations and individuals:

-

63% provided information related to the attacks

-

36% allowed visitors to provide some form of assistance to victims

-

26% allowed individuals to seek assistance from others and from relief organizations

While many Americans relied on television to provide up-to-the-minute news, the actions enabled by the Web demonstrate its importance as a component of the public sphere, and a resource in a time of crisis. It also demonstrated the importance of Webmasters’ ability to adapt existing site elements and create new site features.

-

Government Web sites retooled quickly to allow individuals to provide tips in the terrorism investigations and to help people find means to provide assistance to victims and their families.

-

Religious, educational, and personal sites were particularly active in helping people both provide and obtain assistance.

-

By contrast, very few Web sites enabled political advocacy (e.g. signing a petition, or communicating policy preferences to government officials).

Adaptive and interactive features on many kinds of Web sites made it easier for people to obtain and provide various kinds of information and assistance both online and offline, as well as to share their response to the attacks with others, and to lobby for political action.

In sum, the Web was a significant component of the public sphere, enabling coordination, information-sharing, assistance, expression and advocacy in a crisis situation. In addition, these findings demonstrate the value of Webmasters and other content producers as resources to be deployed in a time of crisis.

Introduction

The terrorist attacks in the U.S. on September 11, 2001, stimulated intense and widespread reactions by many around the world. It is well known that online traffic picked up dramatically at many Web sites produced by news and government organizations, search engines, and portals. The increased traffic to high-profile sites was only part of the story, though. In an article posted on News.com the afternoon of September 11, Stefanie Olsen noted that within hours of the attacks individual New Yorkers and others around the world created personal Web sites as well as used email and chat applications to check in with each other. She also reported on the immediate change in several New York corporate Web sites – including Marriot Hotels, Morgan Stanley, and the law firm of Sidley Austin Brown and Wood – to report on the status of employees and visitors. Prodigy Communication created a National “I’m Okay” Message Center, http://okay.prodigy.net/, designed to help people locate friends and family with whom they had lost contact during the attacks.

[in a crisis]

Lucy Fisher and Hugh Porter, writing a week after the attacks, catalogued some of the ways that Web producers immediately responded to the events. Their list of producer actions included the creation by hackers of mirrors of news sites to help Web users gain quicker access to breaking news, the posting by the producers of professional psychology associations of guidance on handling emotional distress and talking with children about the attacks, and the blacking out of Web sites around the world by many kinds of producers, temporarily replacing their sites’ regular content with “a picture, a message, or a list of other sites doing the same.” Some site producers – especially news organizations such as CNN.com and MSNBC.com – turned to content delivery networks such as Akamai to handle the dramatically increased demand for content. Major search engines and portals reworked their approaches to serving Web users. Google, for example, transformed itself from a pure search tool to something closer to a destination or portal site, a significant departure from its carefully cultivated strategic positioning.

This report analyzes how the Web itself changed in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks. The primary aim is to examine how many Web producers created new kinds of Web sites and online activities, and how other Web producers changed their existing Web sites to respond to the cataclysmic news. This report also explores how those changes in much of the content of the Web were embraced and exploited by online Americans.

At one level, this study is meaningful because it explores how pliable and fecund Web content can be – and how useful that is to those who access the Internet. At another level, it is important to explore how the creation of new online material – much of it encouraging civic participation, political debate, and policy advocacy – can affect the behavior and attitudes of Internet users.

Did all the ferment on the Web encourage political activity and civic engagement? Our argument is that the changes in the content, features and structure of the Web probably were a factor for some Americans in shaping their response to the events of 9/11 and beyond.

Methods

This report is based on two independently collected data streams: an archive of Web sites related to September 11, and a series of daily telephone surveys of individuals about their online behavior in the days and weeks following the terrorist attacks.

Our study of the behavior of site producers, and the structures they created to enable online actions, comes from an analysis of Web sites archived between September 11, 2001 and December 1, 2001. During this time, the authors worked with the Pew Internet and American Life Project, the U.S. Library of Congress, the Internet Archive and volunteers from around the world to identify and archive URLs that were likely to be relevant to the question of how Web site producers were reacting to the events of September 11 (http://september11.archive.org/).

The analysis presented here is based on an examination of Web sites produced by nine types of groups: 1) news organizations such as CNN, the New York Times and Salon.com; 2) federal, state and local government agencies; 3) corporations and other commercial organizations; 4) advocacy groups; 5) religious groups, including denominations and congregations; 6) individuals acting on their own behalf; 7) educational institutions; 8) portals, and 9) charity and relief organizations.

The archive was created by performing systematic searches for URLs produced by these sets of actors. Links to other URLs were followed to find more sites with relevant content. In most cases, the salient feature of these sites was content referring to the attacks and/or their aftermath. In some cases, the absence or removal of such content was salient. These collection efforts identified nearly 29,000 different “sites.” Each site was archived on a daily basis from initial identification some time between September 11 and mid-October until December 1, 2001.

The objective of the archiving activity was to preserve not only the bits and the content, but also the actions and experiences that were enabled by each site. By capturing pages and sites along with their links to other sites, the archiving tools preserved an interlinked Web sphere, characterized and bounded by a shared object orientation to the September 11 attacks. The sampling strategy for this study was designed to include a broad representation of site producers and to focus on those sites that were added to the archive soon after September 11. It yielded a sample of three “impressions” or site captures of the different Web sites. A preliminary analysis of the site pages eliminated those without content relevant to the September 11 events, as well as those not captured in a readable format by the archiving tools. These methods resulted in a pool of 247 intact, coded sites that could be used for analysis. This refined sample of Web sites was then examined closely by trained observers to assess the range of actions made possible by site producers.

Our analysis of the behavior and attitudes of Internet users comes from daily surveys by the Pew Internet and American Life project in the six weeks following September 11. The surveys employed random digit dialing to reach adults across the continental United States. The data were then weighted according to a special analysis of the March 2002 Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey to account for non-response bias in telephone surveys.7

Online structure for action

Online structures enable online and offline actions. Online survivor databases, for example, allowed those in the area of the World Trade Center to broadcast their status globally, and provided a tool for many to look for missing loved ones in hospitals and other venues. Our analysis suggests that the seven different kinds of online structures were created in the wake of 9/11 events and that facilitated seven kinds of activities by Internet users: (1) getting information; (2) providing information; (3) getting assistance/support; (4) providing assistance/support; (5) allowing personal expression; (6) accessing others’ expression; and (7) engaging in political advocacy. Here is a more detailed description of what we found, in order of how prevalent the content was on the Web sites we examined:

Getting information

Almost two-thirds of the Web sites we examined (63%) provided direct and specific information about 9/11 events and the continuing and sprawling news developments that followed. On these sites visitors could obtain news and information about the terrorist attacks, and the subsequent rescue and recovery operations, civic response, criminal investigations, military response, terrorism in historic and political context, etc. Content associated with this action included news, information, and photographs produced by professional (for profit) organizations, nonprofit organizations, and individuals (amateurs). News organizations’ Web sites and government agency Web sites were the ones that most commonly enabled this action – almost all of them did so. In addition, a significant proportion of educational sites (76%) also allowed it.

Accessing others’ expression

More than half of these Web sites (55%) contained some personal views and opinions of the sites’ creators. These sites provided visitors with opportunities to examine others’ responses to the attacks. Memorial sites, typically created by individuals and educational institutions, and personal blogs, were the sites that facilitated the user action of accessing thoughts and emotions expressed by others on the Web most frequently. Significant numbers of corporate, news and religious sites enabled this action as well.

Offering personal expression

More than four in ten Web sites (44%) allowed visitors not only to view others’ expression, but also to post their own reactions and perspectives about the terrorist attacks, the subsequent rescue and recovery operations, and governmental and civic response. This category also includes the expression of religious and spiritual views. In addition, this type of action includes the capacity for site visitors to join in communal expressions of grief and mourning, e.g. by lighting a virtual candle or adding a message to an electronic condolence book. Some sites which had existed prior to the attacks but had not previously allowed site visitors to contribute to the site developed new features in the weeks after September 11 that enabled personal expression. For instance, some government and corporate sites which had previously restricted site visitors to obtaining information, created new online structures after the attacks by which visitors could post responses. Personal Web sites, news sites, educational sites, and the sites of charitable organizations were the ones that most commonly facilitated this action.

Providing assistance

More than a third of these Web sites (36%) provided online structure that enabled their visitors to assist victims, and the families and friends of victims. These sites facilitated action in support of various public and private relief work, such as rescue and recovery efforts, counseling, education, criminal investigations, community organizing, and solidarity-building activities. They also allowed people to contribute money to relief efforts; offer help to community organizers, service providers and educators; and obtain symbolic merchandise (flags, shirts, etc.) and content (images, songs, texts) facilitating participation in solidarity-building efforts. A surprisingly wide range of sites enabled this kind of action, including portals, educational sites, personal Web sites, religious sites, charitable sites, and government agency sites.

Getting assistance

One in four Web sites (26%) carried features or content that made it easier for survivors and the families of victims to obtain the help they needed, e.g. in locating missing persons or registering for various forms of longer-term assistance. Some of the Web-based services provided information for those in the immediate vicinity of the attacks; others provided or sought information about individuals who were in the immediate vicinity. Examples of these services included registries of victims, lists of those missing in the attacks, lists of survivors (“I’m okay” sites), and resource and referral directories. Government sites and educational sites were the ones that most commonly enabled this action.

Providing information

About a tenth of these Web sites (11%) enabled Internet users to contribute newsworthy information to the site. For example, individuals were able to provide “tips” to authorities related to the investigation of the terrorist, and later the anthrax, investigations. Other sites enabled individuals to post information about the attacks and the rescue/recovery operations that were underway. The sites that most commonly facilitated this action were educational sites and government sites.

Political advocacy

Finally, 6% of these sites allowed users to engage in political advocacy by conveying their policy preferences to government officials. For example, individuals could sign online petitions, send email to government representatives, read or post policy positions in online discussion groups, or contribute money to interest and advocacy groups that were lobbying for particular forms of political action. Unsurprisingly, the Web sites of advocacy groups were the most common online structure for this action.

Many sites combined two forms of online structure: They allowed users to engage in certain actions “on-site” and they also linked to other sites where other kinds of action were possible. We refer to this latter form of structure as “coproduced,” and note that coproduction through links allowed Web site producers to expand the number of actions they were facilitating.

Seventy percent of the sites that facilitated providing assistance did so via coproduction; 80% of the sites that allowed visitors to access expression, and 75% of the sites that allowed visitors to provide expression, did so on-site. Personal sites were much more likely to coproduce online structure than any other type of site producer. Business and advocacy producers were much less likely to do so. Advocacy, religious, educational and business producers were most likely to produce on-site structure to facilitate online action by their site visitors.

Online actions by Internet users

It is important to remember that the online activities by Internet users after September 11 were usually part of a larger number of things they did to learn about events and respond to them. Pew Internet & American Life surveys at the time showed, for instance, that Internet users were avid television watchers and newspaper consumers – more so than non-Internet users.

The Pew Internet Project surveys also showed that many Americans – Internet users and nonusers were responding in some personal way to the attacks. We asked respondents if they had engaged in any of five different offline activities related to September 11: attended a religious service, tried to donate blood, attended a meeting to discuss the attacks, flown an American flag outside their home, or given money to relief efforts. By September 19 – the first day for which a representative sample is available — the mean participation rate in offline September 11-related activities had climbed to 1.36; by September 25, the mean had reached 1.99 activities.8 Among those respondents surveyed between September 12 and October 7, nearly 30 percent had participated in three or more activities, 56 percent in one or two activities, and 15 percent in no activities. In the discussion below, the online behaviors among respondents are contrasted with their level of participation in offline activities.

What were Internet users doing during these weeks? We analyzed the level of Web usage they reported, the types of sites Web users reported visiting, and the types of action in which Web users report engaging are discussed below

In the first weeks after the attack, overall use of the Internet declined. Compared to Internet use on an average day before September 11, the percentage of Americans using the Internet on a typical day declined by between 8% and 12% in the first days after the attacks. The number of Americans using the Internet on a typical day did not return to average levels until the beginning of October. This decline in overall usage was noted among all types of Web users, including the most frequent and most experienced groups. However, while overall Internet usage declined, those reporting using the Web for news increased considerably, as the percentage of Internet users reporting getting news from the Web on a typical day rose to 25%-28% of Internet users after the attacks from 22% on any given day in the four weeks prior to the attacks.

Survey respondents were asked about their visits to eight different types of Web sites, corresponding to the producer types examined in the site analysis discussed earlier in this article. All but 11% of the respondents report visiting at least one of the eight types of Web sites prior to September 11, and 26% report visiting four or more of the site types. In the 6-week period following September 11, 46% of the respondents report visiting at least one of the types of sites. However, it is clear that most Web users focused their efforts on relatively few types of sites: fully one-third of those who visited any of the types examined reported visiting only one or two or three of them. At the same time, it is clear the more frequent users of the Internet visited a somewhat wider variety of sites as a result of September 11.

Many Web users visited press sites. Nearly one-quarter of all Internet users reported visiting a press site as a result of the September 11 events. None of the other types of sites were visited by more than ten percent of the Internet users as a result of the terrorist attacks. This suggests that although the Web enables virtually anyone to be an information provider, in times of crisis, press organizations still have unique importance to Internet users. More frequent Web users were more likely to visit every type of site than less frequent Web users. However, there was little relationship between participation in offline activities related to September 11 and visiting sites produced by most types of site producers.

What online actions were performed on these Web sites? Nearly half of all Internet users report using the Web to find news about the terrorist attacks. More than one-third of the Internet users report using the Web to find information about the reaction of the financial markets to the attacks. About a quarter of the Internet users sought out information about Osama bin Laden or Afghanistan. More than a quarter of Internet users used the Web to post or read the opinions of other individuals. About one-fifth of the Internet users downloaded a picture of the American flag, or sought information about victims or survivors. Not surprisingly, more frequent Internet users were more likely to engage in every single action examined than less frequent Internet users. However, engagement in offline activities related to September 11 was connected only to online actions associated with expression; online actions related to information, advocacy or assistance were not associated with offline activities.

The last set of analyses presented here assesses the extent to which Internet users found the Web helpful. Respondents were asked if they believed the Web helped them to “learn what was going on” or to “connect with people.” One fifth of all respondents said the Web helped them “a lot;” frequent users of the Web were more than three times as likely to say the Web helped them “a lot” than less frequent users of the Web. Similarly, about one–fifth of the respondents indicated that the Web played a major role in shaping their views. Finally, Internet users who used the Web for political advocacy were most likely to believe the Web helped a lot or played a major role in shaping their views.

Implications

Online actions are, in part, a function of online structures provided by producers. This analysis illustrates some of the synergies between these two types of data. While the data presented in this analysis do not account for the frequency with which users visited different kinds of sites offering different online structures – which would allow a full analysis of the relationship between online action and online structure – some preliminary estimates can be made. For example, the percent of Internet users who report getting information from the Web in the days and weeks following September 11 may have been a function of the number of sites that facilitated this action. Similarly, the relative paucity of sites facilitating advocacy or enabling the provision of information would have accurately predicted the relatively few users who reported engaging in this action. While the provision of structure does not guarantee action, it is clear that absent online structure, online action is not possible. Several implications can be drawn from these findings.

In addition, the findings illustrate the importance of the Web as a significant component of the public sphere, enabling coordination, information-sharing, assistance, expression and advocacy in a crisis situation. In addition, they demonstrate the value of Webmasters and other content producers as resources to be deployed in a time of crisis. Former Federal Communications Commissioner Reed Hundt has argued that one lesson to be drawn from the events of September 11 is that in order to maintain an effective communications system in the face of any calamity, the Internet should be protected and promoted as a primary network, encouraging the private sector and using the resources of the public sector to make it faster, more robust, ubiquitous, and better integrated with other media.